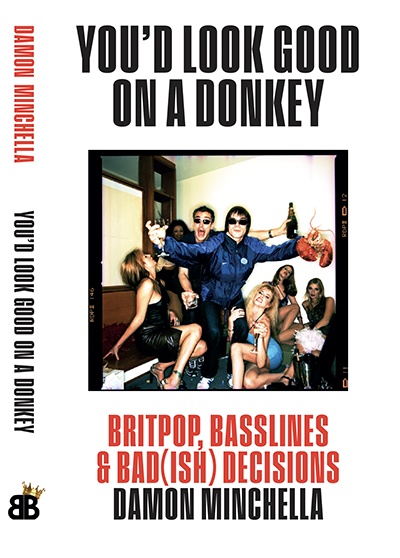

Former Ocean Colour Scene bassist and founding member, Damon Minchella, has a ton of great stories to tell, so he’s written his autobiography, You’d Look Good On A Donkey: Britpop, Basslines & Bad(ish) Decisions.

It’s a fun read. In his friendly and chatty style – imagine he’s telling you his rock ‘n’ roll tales over a pint in the pub – he shares anecdotes of ‘90s indie-rock excess, including a close call with the drug squad, and telling Paul McCartney one of his guitar solos was shit!

Minchella, who left Ocean Colour Scene in the early 2000s, is extremely honest about his time with the group – he reveals the highs and the lows – and he also recounts when Leonard Cohen told him to fuck off, reminisces about his time with Paul Weller, shares his memories of playing with The Who at Live 8, and supporting Oasis on their 2025 world tour, as part of Richard Ashcroft’s band.

‘He shares anecdotes of ‘90s indie-rock excess, including a close call with the drug squad, and telling Paul McCartney one of his guitar solos was shit!’

Born and bred on Merseyside, Minchella now divides his time between Wales and Italy. Say It With Garage Flowers spoke to him earlier this month to find out why he decided to write his memoir, and we got him to tell us some of his amusing stories and reflect on his career.

“I’ve never been arsed what people think of me,” he says. “Apart from my closest friends and family, I don’t give a flying fuck what people think. I don’t care – it’s not a book about making friends…”

Q&A

I enjoyed your book – it’s a fun read. Why did you decide it was time to write an autobiography?

Damon Minchella: It was my wife’s fault, to honest. We would be out walking the dogs or in the pub with some friends, and I would just remember a story that I’d never told her. It kept on happening and she said was like, ‘You’ve got to write your book before you forget it all…’

So, there was that, and I was in Italy for an extended period, doing my citizenship and getting my passport – I had to be there for a specific amount of time, with nothing really to do, so, I thought: ‘I’ll just write – I’ll start and see what happens…’

So, I started it, and it was like, ‘bang!’ All these things just came out… The process of writing just released loads of memories, but not in a linear fashion, obviously…

I want to talk about that because you haven’t approached the book in the traditional way. It doesn’t start at the beginning, with when and where you were born, etc. It begins with Leonard Cohen telling you to fuck off, in a hotel in New York, in the early 2000s…

Yeah – as soon as I started writing, that was the first thing I wrote – ‘Once upon a time, Leonard Cohen told me to fuck off….’ and I thought, ‘Oh – that’s good, I’ll have that as the start.’ And then I started thinking of chapter titles… It’s a bit like writing a song – if you come up with a good title, then that kind of informs what it might be about.

All the chapter titles were sort of random memories, so I started putting them in some sort of order, that wasn’t chronological, and then I just wrote the book from there. After about three months, I had to come back to Wales for a couple of weeks, and I was in and out doing gigs with Richard [Ashcroft]… I thought, ‘Well – I’ve got half the book done already…’ So, then I finished it off.

Are you a natural writer? Does it come easily to you?

Yeah – I think so. It’s because I read a lot as well – I’m an obsessive reader. Obviously writing a book is different from reading what someone else has written, but I like to think I’m reasonably eloquent, but I like swearing as well. So, it’s a nice collision – I’m an eloquent gobshite.

Your writing style is very chatty – it’s as if you’re telling the stories to someone over a pint in the pub. Going back to Leonard Cohen – you started to speak to him when he was sat in a hotel dining room…

And he immediately told me to fuck off – before I’d even finished the sentence. As I say in the book, a lot of people might’ve been offended by that, but I thought it was genius. I wanted Leonard Cohen to be Leonard Cohen, and he nailed it…

Kim Gordon from Sonic Youth told you to fuck off too, didn’t she?

Yeah – weirdly, they were supporting us [Ocean Colour Scene], which was wrong – we should’ve been supporting them… It was an outdoor gig, and I was in the portacabin dressing room. She walked past and I just went: ‘Kim!’ She went, ‘Fuck off!’ and carried on walking – she didn’t even break her stride. That’s what I wanted from her.

That’s pretty cool. How are you when people who aren’t famous recognise you and ask for an autograph or a chat etc?

If people want to come up and talk to you because they like your music, to be rude to them is terrible. I was having dinner with Chad Smith from the Chili Peppers once, who’s a lovely fella. Dustin Hoffman was sitting at the table next to us – someone wanted his autograph, but he was so fucking rude to them… Those people are why you’ve got a nice house…

You did once tell Paul McCartney one of his guitar solos was shit! It’s mentioned in the book… It was in Studio Two at Abbey Road, when he, Paul Weller and Noel Gallager were recording a version of Come Together, as The Smokin’ Mojo Filters, for The Help Album – for War Child – in 1995. You were joking, but how did he take it? Did he see the funny side?

He did – after the initial shock. He’s not used to anybody around him saying anything apart from: ‘Yes, Paul, no Paul, three bags full, Paul…’

What were you thinking?

I just thought, ‘I’ve got to say it…’ I do have social airs and graces, but I also have the ability to go, ‘Oh, come on!’

Your family has a link to The Beatles – your mum went to school with George Harrison, and your dad was almost the tour manager and van driver for The Silver Beatles, before they became The Beatles…

Yeah, but Neil Aspinall go the job instead. When I saw Neil [at Abbey Road], I said: ‘You’ve got my dad’s job…’ It was amazing that McCartney even knew what my last name was, and he remembered my dad as well. That’s probably why he didn’t mind me telling him his guitar solo was shit…

The title of the book, You’d Look Good On A Donkey, comes from something Ian Brown from The Stone Roses said to you. The Roses were a big influence on Ocean Colour Scene in the early days, weren’t they?

It’s safe to say that without The Roses, you wouldn’t have had my band, The Verve or Oasis – what people labelled ‘Britpop.’ I know it’s on the front of my book, but ‘Britpop’ didn’t really exist for the musicians doing it… Five or six years before, The Roses paved the way for it on a commercial level, but they were more of an influence on our attitude and style – they blew us all away. They were in their mid-twenties and me, Ashcroft, Noel and Liam were in our late teens. We saw this band who had it all but were cool as fuck. We were like, ‘shit – we can do that.’

‘I’ve never been arsed what people think of me. Apart from my closest friends and family, I don’t give a flying fuck!’

You used to live near Ian Brown, in Notting Hill, didn’t you? And Brett Anderson from Suede lived nearby too – you call him ‘a plonker’ in the book…

Yeah – he lived round the corner, and so did Justine Frischmann – when Damon Albarn was seeing her. Me and him [Damon] never got on, but I always got on with her, which annoyed the fuck out of him. She’d always come and talk to me, but he’d be looking the other way.

The book’s very honest – you don’t mind who you upset, do you? Are you not worried about some people coming back to you over what you’ve written?

Not in the slightest – I’ve never been arsed what people think of me. Apart from my closest friends and family, I don’t give a flying fuck what people think. I don’t care – it’s not a book about making friends…

I was interested to read that when you were young, you didn’t have any interest in music – you were into football, messing around on your bike and watching war films – but one morning you heard The Cutter by Echo & The Bunnymen on the radio, and it changed your life…

Yeah – totally. Prior to that, music was always on – my mum had a good record collection – but I wasn’t particularly arsed. It was always the shit my sister was listening to, which was pop music. I’d never thought ‘Wow – this is incredible! – until The Cutter came on breakfast radio. It was like a sound from another world. I was like, ‘What the fuck? I need to know what this is.’

‘The first gig I ever saw was The Bunnymen on the Ocean Rain tour – at Birmingham Odeon. I got down to the front, they came on and I was like, ‘Well – this is it: I’m gonna do that!’

Weirdly, The Bunnymen were in Smash Hits and my sister had every copy, so then I saw what they looked like – they looked as otherworldly as their music. So, that was it – I went and got the single.

You didn’t have a record player – you borrowed your sister’s…

I probably never gave it back. The first gig I ever saw was The Bunnymen on the Ocean Rain tour – I’d moved from Merseyside to the Midlands, and I went to see them at Birmingham Odeon. I queued up on me own, I got down to the front, they came on and I was like, ‘Well – this is it: I’m gonna do that!’ I thought the guy on the right, Les Pattinson, who was on bass, was the coolest, so I wanted to do that.

Later on in your career, Ian McCulloch asked you to join The Bunnymen, didn’t he?

It was like a weird circular thing in my life. By that point, I’d obviously done loads of music and I’d met Mac a few times… He’s a character – let’s put it that way…

But you turned down the opportunity….

Yeah. I’m mates with Les Pattinson, who is the reason why I became a bass player. I told him and he said, ‘Nice one – you’ve dodged a bullet there…’ It’s not the easiest touring environment.

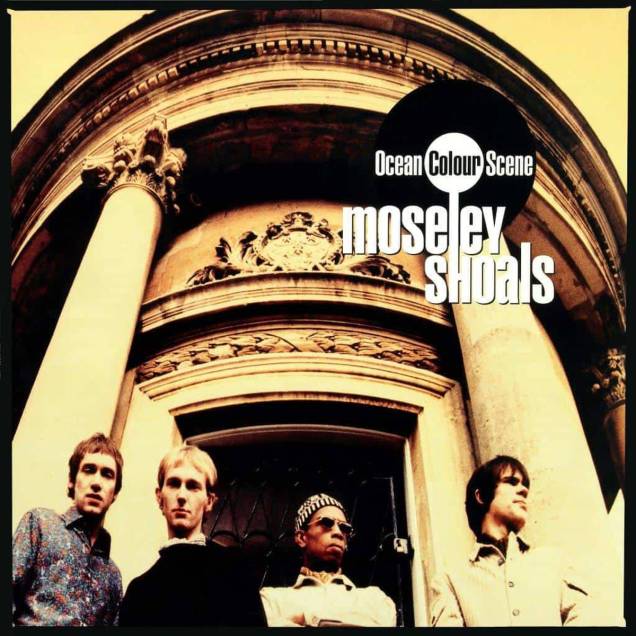

In the book, you write about the early days of Ocean Colour Scene, and the struggles you had making your first album – you had to re-record it a few times. You were signed to the Fontana label but, after hearing the demos for the second album, which, funnily enough, included future hit, The Day We Caught The Train, they didn’t want to work with you anymore…

It was crazy – they hated us so much that they just wanted to get rid of us. There was another song [on the demo] that ended up being on Moseley Shoals too. I can’t remember what it was… It took a year to end the relationship – we couldn’t do gigs because of all the legal bullshit.

‘The hellscape of making the first album had sucked all the life out of what we wanted to do’

So, we got ourselves the best sort of space we could afford, which was a horrendous sort of little backroom in a studio. But that’s when we just thought, ‘Right, let’s just fucking be us now..’ The hellscape of making the first album had sucked all the life out of what we wanted to do – we kept changing producers…

It was the typical major record label thing – they sign a band that sounds like something, you start making a record and then some other music scene happens, so they want a different producer to fit in with that. And then another scene breaks, and they want another producer to fit in with that. By the end of it, you’ve ended up with a very expensive pile of shit.

It was a struggle financially, wasn’t it? You were on the dole right up until The Riverboat Song was successful, weren’t you?

Yeah – apart from me and Steve [Cradock – Ocean Colour Scene guitarist] touring with Weller, we had nothing. All our mates who weren’t in the band had proper jobs and had bought flats and had proper cars, and we were struggling to get the bus fare to get to the studio.

People say we were really lucky because of TFI Friday and the Weller connection – he liked the band – but that wasn’t luck, it was self-belief and stubbornness that got us to that position. Everyone else who’d been dropped by a major label would say, ‘we’ve got no money – let’s pack it in…’

I didn’t realise how much Andy Macdonald, who had the Go Discs! label, helped you out ahead of you making Moseley Sboals...

Yeah – he’s an amazing person and I talk about him in the book. He loved our demos and what we were doing, and he wanted to sign us, but he’d just signed Travis, and it was quite a small label. He had Weller, who was exploding, and Portishead, who were doing well. He signed some other dancey stuff too, so he couldn’t take us on, but he said: ‘Here’s some studio equipment and £10,000 in cash.’ We were like, ‘What the fuck?’ Ten grand in 1995 was a fortune.

You mentioned not being able to afford the bus fare to get to the studio, but how was it when you suddenly found yourself in the spotlight and making serious money. How was fame? Was it a bit of a headfuck?

Not really – it doesn’t happen in a huge explosion, it’s day-to-day. As it was incremental, it was easier to deal with. It’s not like you’ve suddenly won The X Factor...

And you’d put the effort in early on…

Yeah, but I think it was also because we’d spent so long in the wilderness. We’d already done the first album on a major label thing, and that all went wrong. We stuck to our guns, so it was more validation really – it was like, ‘Okay – people like our music…’ It wasn’t just the four of us, our manager, a few friends and Andy Macdonald anymore…

You go from being flat broke to looking at your bank account and going, ‘Jesus Christ!’ And, instead of everyone around you saying, ‘You’re shit, split up’ – everyone’s saying, ‘Wow – you guys are amazing!’ That’s going to inflate anybody’s ego, but it’s how you deal with it is the test.

Ocean Colour Scene were a band that were liked by the people but disliked by the music press, who called you ‘Dadrock.’ Why did the media hate you so much and did it bother you?

I know why they hated us… The first time round the music press said Ocean Colour Scene were going to be the biggest band in the world – they hyped us up and then we had the disaster of making the first album, which took three years rather than three months, by which point they’d moved on – they were like ‘You guys are dead to us…’ So, we came from nowhere – it was completely unexpected.

They presumed we’d split up and then suddenly we’re on Top of the Pops and daytime Radio 1 – and they, the purveyors of good taste, were like, ‘How dare you.’ We circumvented them and became massive, so they had to slag us off.

Then there was Britpop and then Britrock, which I suppose, were positive terms – everyone was talking about it – but we got called ‘Dadrock, which was supposed to be really insulting, because it was the music your dad listened to. Well, my dad had really good music taste…

Do you think Ocean Colour Scene have gained critical acclaim as time’s gone on?

I think so. I hate the word ‘authentic’, but we were true to ourselves, we had talent, quality, and great songs. At the time it had a label, but then, years later, people go: ‘This is really good…’

It’s like Free – they’re only really known by the vast majority of the general public for All Right Now because it was in a chewing gum advert. It’s by far their worst song – their second, third and fourth albums are astonishing. They were never cool, but, over time, people are like, ‘We should listen to Free…’ Things that are written off and labelled as X, Y, Z… Now those labels don’t matter…

‘We didn’t like the closed-mindedness of the whole mod thing. It was supposed to be modernism – looking to the future – rather than thinking it’s all about 1967’

In the book you write about how Ocean Colour Scene were often labelled as a mod band, but, other than Steve, you weren’t mods, were you? Simon [Fowler – singer] was into folk music, and, like you, The Velvet Underground, and Oscar [Harrison – drummer] liked lovers rock and dub. You did embrace the mod look, though…

Yeah, and on the artwork, and it didn’t help that we had scooters… The look is good, and the clothes are great, but we didn’t like the closed-mindedness of the whole mod thing. It was supposed to be modernism – looking to the future – rather than thinking it’s all about 1967.

You played bass in Weller’s band, but you weren’t a fan of The Jam, were you? You prefer The Style Council – although you don’t like some of the ‘80s production on their songs…

I think it stems from when I was at school. Once I discovered The Bunnymen, I got into The Velvet Underground, The Stooges and Suicide – all that kind of stuff. You get into all this weird, cool-as-fuck music where nothing is straightforward, like the lyrics and the look.

When I moved from Merseyside to the Midlands, my mates at school were all into The Jam, but you’d hear the music and it was too obvious – they looked boring and you knew what every word meant… There was nothing to unravel in your mind – there was no mystique.

Obviously, Weller wrote some fantastic songs in The Jam, but I think the songs he wrote in The Style Council are way more interesting, but the problem with a lot of The Style Council stuff is the production, which is very ’80s…

What did playing with Weller teach you? Did you develop as a musician and learn to improvise?

Yeah – I learnt to improvise a lot, and to be really committed – not that I wasn’t committed, as I’d been through the wilderness of being on the dole and making tunes in a really shit studio… It was more about playing live – the sheer attitude of it and how it was the most important thing right now… It doesn’t matter if you make a mistake – it’s onto the next bit and give it your all.

One of the main things Paul gave me was the chance to explore loads of music that I wouldn’t have thought of listening to, like Free and Traffic. The first time I listened seriously to The Verve was when he gave me a cassette which had History on it.

I saw The Verve when they did their first album. Me and Simon [Fowler] saw them at some tiny venue in London – they were good, but it was when they were doing that sort of psychedelic sonic space jam stuff… So, Paul opened my eyes to The Verve, which is kind of weird, because I would go on to work with Richard. That’s not to say that Paul was open-minded about all kinds of music – I’d play him some stuff and he just refused to listen to it.

‘One of the main things Paul Weller gave me was the chance to explore loads of music that I wouldn’t have thought of listening to, like Free and Traffic’

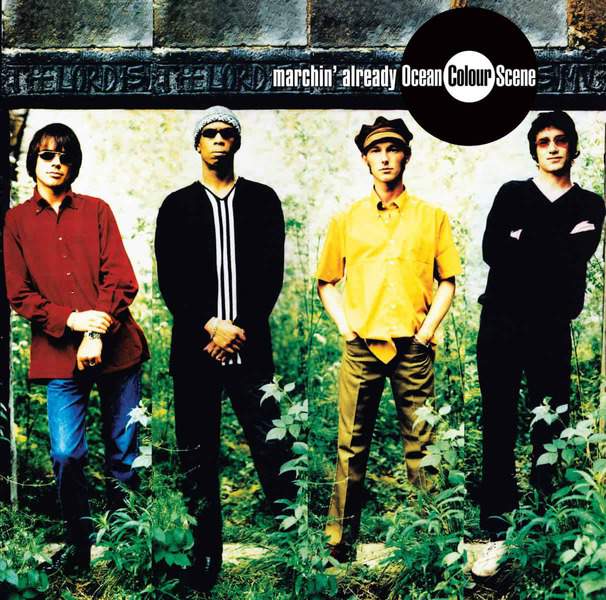

We talked earlier about how honest the book is. You’re very candid about the bad times in Ocean Colour Scene as well as the good times. When the band got a lot of money, that led to a lot of drugs too, which, ultimately, caused a rift between some of the members, didn’t it?

Yeah – it happens to every single band, if they’re inclined to go that way. You’ve suddenly gone from no money to shitloads of it, and, if you’re in a band, you tend to do drugs anyway… And now no one’s telling you you can’t, and you’ve got lots of money, so you can afford it. You also then got extra people involved, like partners…

And all the hangers-on…

Yes – you’ve got a lot of people talking and also lot of pressure to follow up the next record, to make sure you have another hit. All of a sudden, it’s rare that all four people in the band and their manager are together on their own – all of a sudden, you get a little fracture.

Half the band are doing uppers and half are doing downers, so that immediately creates a sort of energy rift, and as soon as that starts, when you’re in the band, small things become big. People – particularly blokes – don’t tend to talk about how they’re feeling. So, you get the two who are smoking a lot of weed [Simon and Oscar] and won’t go into the studio because they think the other two are just going to have a go at them…

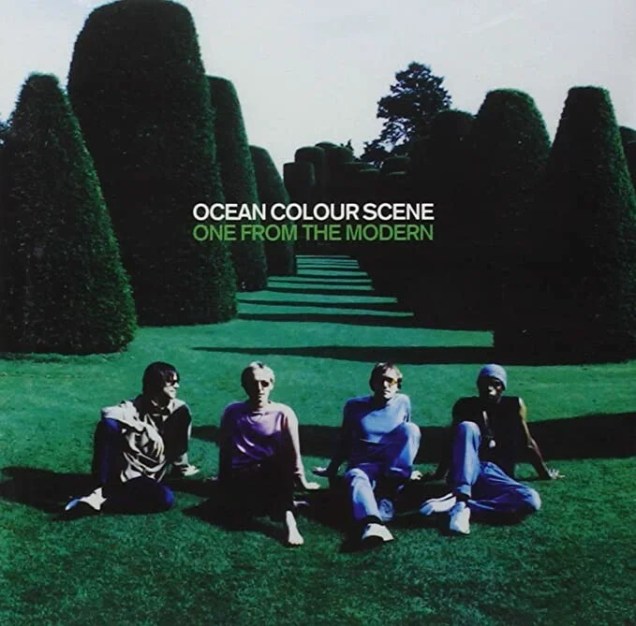

‘I can’t listen to One From The Modern now, because I know how it was made…’

That all came to a head on One From The Modern, which was basically mine and Steve’s record. If we hadn’t pushed it, it would never have got done. It wasn’t the record that me and Steve wanted to make, but it’s still a very good record. I can’t listen to that record now, because I know how it was made… I was talking to someone for a podcast yesterday, and they said One From The Modern is their favourite album. I was like, well, good for you, but it’s not mine…

Since you left Ocean Colour Scene, in the early 2000s, you’ve seen Steve and you’ve seen Simon, but you haven’t spoken to Oscar, who you fell out with in a big way, leading to you leaving the band. Would you like them to read the book?

I know they will… Oscar won’t like any of it… I think if Steve and Simon get to the end of it, they’ll be like, ‘All right, fair play…’ because I’ve got a lot of love and respect for the band and particularly for Steve and Simon. If they only get halfway through it, I’m expecting my phone to be quite hot…But if they get to the end, they’ll go: ‘We get it…’ They were there as well – they know what happened. It’s not like I’ve invented some sort of Stalin-esque re-reading of our lives.

We talked about drugs… There’s a good bit in the book where Ocean Colour Scene accidentally join a drug cartel…

(Laughs). That was a very bizarre time – it was when we were finishing off One For The Modern, which was sort of the pinnacle of the band being at their most excessive. We were all doing a lot of drugs and we had a tried and tested dealer, but we didn’t know the police were keeping tabs on him…

They see him going into a big studio in an industrial part of Birmingham, where loads of trucks go, and they think the band is being used as a transportation front for an international drug cartel, which we didn’t know the guy was part of.

Bizarrely, the other three guys in the band were buying their drugs with cheques… so the police found that out as well…

There was a paper trail…

I’m not being funny, but just go to the cashpoint… I’d moved to London, so when I was in Birmingham, I stayed at a hotel – the police never saw the guy come to my house, but they saw him go to the other guys’ houses as well, not just the studio… Obviously, we weren’t a drug cartel, but, you know, the studio got raided by the armed drug squad…

‘We were all doing a lot of drugs and we had a tried and tested dealer, but we didn’t know the police were keeping tabs on him…’

And your manager, Steve’s dad, was an ex-copper…

Yeah – and fortunately he was able to sort of deal with it without anyone having a heart attack. He understood who we needed to talk to. Obviously, there were going to be some arrests and cautions, but then eventually they were going to say, ‘ Okay, it’s not you guys…’

It made the TV news and you had to distract your mum when she saw the story on the telly…

Yeah – she’d come in from the kitchen, turned on the telly, and it panned across a picture of the band… then it was just a picture of me on screen, with the news anchor saying, ‘What next for Ocean Colour Scene?’

There’s another police-related story that didn’t make the book. You once signed autographs for the police when you had some drugs hidden in the glove compartment of your car…

Yeah – I’d bought a sports car, I’d been working late in the studio, and I was driving back with the top down, playing Public Enemy at full blast. It was when I was renting an apartment not too far from the studio, and the police had cordoned off the road for some reason.

I was thinking, ‘shit…’ They’d blocked the road and they were obviously going to search the car, so I immediately turned off Public Enemy, stopped the car and took my hat off.

A copper came up to me and said [adopts a Brummie accent]: ‘Fucking hell – it’s Damon from Ocean Colour Scene!’ He called his mate over – another copper – and they said: ‘Can we have your autograph?’ They asked me where I lived, opened the roadblock, and let me go. Meanwhile, my heart was pounding…

You were in a great band with singer-songwriter /guitarist, Matt Deighton, and drummer, Steve White, called The Family Silver. It’s now just over 10 years since your debut album, Electric Blend, came out. Is there talk of reissuing it and playing some gigs?

Yeah – there is. It kind of depends on Matt, and also if there’s enough desire for it – not just from the three of us. We’re all of a certain age now… It’s not like when you’re younger, and and it’s like, ‘Great, let’s get in a van and eat frozen pizza, and we can all share a room on tour…’ No chance!

It was a great band – and a pure band. It’s nice when it’s just three people as well, because it just makes everything incredibly important – what each person’s playing. And I do like that stripped-down side of music a lot. It’s a possibility – it’s definitely not a shut book.

I like the bit in the book where you talk about how Steve White calls you on a Wednesday in 2005 and asks you if you want to play a gig with him on Saturday – it turns out to be The Who at Live 8, in Hyde Park…

When anyone asked me to do something, particularly in London, my stock answer was always ‘no’ – I was living in Warwickshire, out in the countryside – but when Steve told me what it was, I was like, ‘Fuck – it’s The Who!’ I went to a little pub just around the corner from my house, and thought, ‘Fuck – I need to learn some Who songs, but I haven’t got any of their records…’

You weren’t a Who afficionado…

No, but obviously they’re brilliant… Apart from a greatest hits album, I didn’t have any of their records, so I didn’t know any esoteric tracks. By the time we’d eventually found out what the setlist was, I’d kind of worked the songs out, and we rehearsed for one hour on the Friday…

That’s crazy… Only one hour?

Yeah – we played Won’t Get Fooled Again twice…

Well, that’s almost half an hour already…

(Laughs) Yeah. We went on stage after Robbie Williams, who’d heroically overrun – everything was running behind and it was insane backstage. Me and Steve weren’t even having a beer because we needed to keep our shit together.

As you both walked towards the stage, Steve said to you: ‘If we fuck this up, our careers are over…’

Yeah – brilliant! And we had to push past Sting and Bob Geldof to get on stage – they were in the way. We didn’t fuck it up – thank God.

I watched a clip of it on YouTube – you can’t see a lot of you because of where the cameras are positioned…

Yeah. I’ve got really short hair for some reason. Clearly, I wasn’t planning on doing the world’s biggest gig ever…

You wrote some of the book while you were on tour with Richard Ashcroft, including the dates supporting Oasis last year – how were those shows?

I think Oasis did 42 shows – we did 24 of them. I’d easily done over 100 gigs with them the first time round. It was a lot more organised this time – it was like clockwork.

What was amazing about it was the euphoria from the audience – even more than the first time round. I think it was that people couldn’t quite believe it was actually happening.

‘Richard Ashcroft is the last of the singer-songwriter rock stars’

And walking out on stage with Richard… We’re the special guests, but we weren’t seen as the support band… We were our own world within the Oasis world and, for those 45 minutes, people were losing their shit and crying – before we’d even played a note…

It was amazing to see so many young people there – there was a whole new respect for Richard, and Oasis and Cast. You’ve got this entire new audience, which is millions of people, who didn’t get it the first time around. Maybe their parents played them the tunes when they were growing up, or an older brother or sister. A lot of the kids in the audience had parents who weren’t even born the first time round…

It culminated for me at the gig in the Chile, which was the best gig I’ve ever done – it was in the old National Stadium [Estadio Nacional in Santiago], which is where the Chilean government used to execute people in the ‘70s.

There’s a monument at the far end of the stadium, but you can see it from the stage – there were 90,000 Chileans and it was like a biblical experience for them. It was utterly incredible – an amazing, life-affirming experience.

Is Richard your favourite musician you’ve ever worked with?

Yeah – he’s the best performer and best singer, and a great songwriter. If you combine everything together… People might say, ‘Oh – Weller is a better guitarist than Richard…’ Yeah, of course he is, but he’s not a better singer than him – that’s for sure – and he’s not a better frontman… And if you combine it with Richard’s fucking aura… He’s the last of the singer-songwriter rock stars.

So, what’s next? Would you like to write another book?

It’s in the back of my head – I’ve got an idea. I left it open in this book that I might do a follow up. It’s going to be music-related, but it might not be part two of a memoir… but then again it might… That sounds really mysterious… I think I probably will do one.

It could be a book about going on tour with Wendy James from Transvision Vamp…

Christ – what an experience that was.

I didn’t know you’d done that, until I read a brief mention of it at the end of the book…

I wish I hadn’t done it. It was Steve White’s fault. We were playing a gig with Weller in L.A. and Wendy James came in, because she knew Steve and Paul.

She was like, ‘I’m putting a band together…’ and Steve said: ‘Ask Damon – he’ll play bass for you…’ And I was like, ‘Yeah – cool…’

So, I went on tour… and oh my fucking God… It was hell. It wasn’t a fun experience at all – it was the second time I’d left a tour halfway through. I just couldn’t take it anymore. I think I left the tour in Madrid, and I didn’t tell anyone.

I remember Wendy sending me an email that said: ‘You will never work with me again.’ I just replied: ‘Obviously.’

You’d Look Good On A Donkey: Britpop, Basslines & Bad(ish) Decisions by Damon Minchella is out now, published by Backstage Books.

For more information, visit: www.backstagebooks.com.