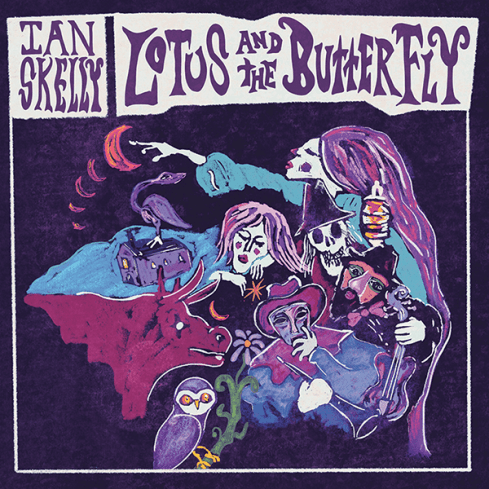

Ian Skelly, drummer with The Coral, releases his third solo album this month, Lotus and the Butterfly, a haunting record of ’60s-inspired, psychedelic sounds and freak-folk that mixes sweet melodies with a dark, raw edge, and is influenced by Love, Captain Beefheart, The Band, Charles Manson and The Beach Boys.

Telling us about the title of the record, he says: “I was thinking of some sort of fucked-up, arthouse ballet thing, crossed with a kung fu movie!”

Welcome to the weird and wonderful world of The Coral.

It’s been a busy few years for Wirral psych-pop band and cosmic adventurers The Coral – in 2021 they released the inventive and ambitious, 24-track double concept album, Coral Island, with spoken word passages narrated by 85-year-old Ian Murray (also known as The Great Muriarty), who is the granddad of band members James and Ian Skelly.

The record was inspired by faded British seaside glamour, childhood holidays to North Wales, end-of-the pier amusements, pre-Beatles rock and roll and jukebox pop.

Musically, its list of influences included Duane Eddy, Chuck Berry, Sun Records, Joe Meek, The Kinks, The Byrds and Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Then last year saw not one but two new records from the band – their eleventh album proper, Sea of Mirrors, which was their take on a surreal, European Spaghetti Western soundtrack, and its companion piece, the pirate radio-themed murder ballads and country-flavoured Holy Joe’s Coral Island Medicine Show, which was only available on physical formats.

As if that wasn’t enough, drummer Ian Skelly is now gearing up for the release of his third solo album, Lotus and the Butterfly, a wonderful and intriguing record that’s inspired by the psychedelic sounds of Love and Captain Beefheart, the darker side of late ’60s Beach Boys – first single, Sweet Love is Skelly’s idea of what the soundtrack to a 1969 biker movie starring Dennis Wilson would sound like – as well as freak-folk, and the country rock of The Band.

Beneath the sweet and pretty melodies, there’s a rough and raw edge – it’s like stumbling across a travelling circus or a country fair while on a road trip and uncovering weird goings-on. Something wicked this way comes?

Recorded in Parr Street Studios in Liverpool, and band HQ, the Coral Caves, it features Skelly’s bandmates Paul Molloy (guitars, bass and keyboards) and Paul Duffy (backing vocals), as well as sleeve notes by Coral keyboard player, Nick Power, who has written a mysterious journal about an explorer in the 1950s who makes field recordings while visiting unchartered territories in Spain and Mexico.

‘Beneath the sweet and pretty melodies, there’s a raw and sinister edge – it’s like stumbling across a travelling circus or a country fair while on a road trip and uncovering weird goings-on’

In an exclusive interview, Skelly tells us about writing and recording the album, capturing magic in the Coral Caves, and how him and the band are always true to their art.

Q&A

You’ve been so busy with The Coral over the last few years – you recorded the double album, Coral Island, which came in 2021, and last year you released two albums: Sea of Mirrors and Holy Joe’s Coral Island Medicine Show on the same day. How have you found the time to make a solo record?

Ian Skelly: A lot of the songs I’ve had since my first album, Cut from a Star [2013]. I had about five of them, but they seemed a bit melancholy at the time, so I binned them, and I started working with Paul Molloy – we were doing Serpent Power stuff…

After you do something on your own, it’s quite a burden, but when I started playing with Paul, I had someone to play off and write against. So, I put the [solo] songs to one side, but during that second lockdown period – I hate talking about lockdown – Blossoms were in the studio [Parr Street, Liverpool] and our James was working with them. He’d get me in in the morning to sort the drums for them, and then I had the rest of the day…

Me mate worked there, and there was a little room in the back… He said, ‘Do you want to do a couple of tunes? It was after I’d released my second solo album, Drifter’s Skyline [in 2020]. So, I said I had a few tunes from years ago…

The concept of the album was originally meant to be me on acoustic, ‘cos I thought nowadays trying to get a full, five-piece band together to gig, tour and travel is quite difficult, so I went in and did it almost like a Ted Lucas thing – it all went to half-inch tape, and it was all live, with just acoustic and vocal.

Paul Duffy, who plays bass for The Coral, came down and we worked on some harmonies. The album was done in two days, but then I sat on it for a couple of months and played it to people who said, ‘This is great.’ But Paul Molloy said there was something about my playing that was dead funky, and he said it would be a shame if I didn’t put drums on it. By then, there was no separation between the acoustics and the vocals, so I thought, ‘How am I going to do this and mix it?’

I ended up going into the room, putting some drums on and thought, ‘Oh, yes – this has got something.’ Molloy did all this great bass playing and guitar work all over it. This album is the follow-up to Cut from a Star – it’s in the same mood.

Drifter’s Skyline had more of a country feel, whereas this album is psych-folk…

IS: Yeah.

I know there’s a concept behind the record – Nick from The Coral has written a fictitious journal for the sleeve notes – but what was the initial idea for it and how you wanted it to sound?

IS: When I make an album… Drifter’s Skyline was done in three days in Berlin – there were no rehearsals. I recorded the songs acoustically and then a mate of mine jumped on and said, ‘There’s a studio in Berlin – let’s go there, get off our cakes and make an album.’

It was more reactive – we didn’t sit down and think ‘it needs to be this or that…’ It was the same with this album, but the rest of the tracking was done in the Coral Caves – there’s a magic in that room that you can’t get anywhere else. It doesn’t feel like a studio or that there’s a clock ticking. The songs were psychedelic anyway – you could’ve put any backdrop to them….

‘The Beach Boys are my favourite band. That’s why a lot of the harmonies and the arrangements on Sweet Love have got those textures on them’

I’ve read that for Sweet Love, you wanted it to sound like something from the soundtrack to a 1969 biker movie, starring Dennis Wilson from The Beach Boys…

IS: Yeah – when I wrote the song, I thought it had that kind of Beach Boys 20/20, lost Manson kind of thing, which is my favourite side of The Beach Boys – they’re my favourite band. That’s why a lot of the harmonies and the arrangements on Sweet Love have got those textures on them.

‘I sent the album to Nick Power and he got really inspired by it – he said it sounds like it’s a guy who is doing field recordings of volcanos and making them into drum beats’

A few of the songs on the album have a dark and sinister undercurrent to them that’s lurking beneath the pretty melodies…

IS: Yeah – there’s a melancholy rage to it. If you’re in a sad, melancholy place, sometimes the only way to get out of it is rage.

It was less about influences in music, and more about painters that I like – Van Gogh and Munch. I wanted to get the idea of those melancholy paintings across. I’m not really musically trained – I don’t know what chords I’m playing half the time. I’ve just picked it up from watching the lads over the years – I think of music and mixing more in terms of painting.

Where did the idea for the journal that’s in the sleeve notes written by Nick come from?

IS: I sent the album to Nick and he got really inspired by it – he said it sounds like it’s a guy who is doing field recordings of volcanos and making them into drum beats. I said, ‘Can I use that?’ It goes nicely with the album.

I love the artwork…

IS: I was going for a sort of European artist going to New Orleans or something… It’s a bit kiddish.

The first song on on the record, You Who Brought Me, has a weird, almost waltz-time feel…

IS: It was a waltz, but then I got bored of waltzes, so I did something different. I wanted that tune to sound like Safe As Milk by Captain Beefheart, which is my favourite sounding record. I just love the murkiness of it – even years later, you’re like, ‘Ah – there’s a conga in there, making up that beat with the drums…’ I wanted it to sound like a track that’s hard to get your head around.

A few weeks ago, I interviewed John Power from Cast and The La’s – another musician from Liverpool – and he is a big fan of Captain Beefheart too. There’s been a few bands from Liverpool who’ve been influenced by him…

IS: When we first started rehearsing in Liverpool, in about ’98 or ’99, there was that sort of post-punk thing. You’d had The La’s and Julian Cope, who was a big influence on the Liverpool music scene, and there was Probe [record shop in Liverpool] – all the musicians who started hanging out with each other were into that. I got into Captain Beefheart through a John Peel documentary that I saw on the telly years ago – I can remember seeing him on the beach doing Electricity and thinking, ‘Fuck – yes!’

In the lyrics of Silver Rail, you mention a ferris wheel – The Coral seem to fascinated by fairgrounds and carnivals. Those were themes on both Coral Island and Holy Joe’s Coral Island Medicine Show …

IS: Yeah – I think it’s where we’ve grown up and live… We always had these Wirral shows that would come to New Brighton, and there would be a big carny thing – they were always the magic moments when you were a kid. It just seems to be in the air round here, but I’m not sure why.

Butterfly is a pretty, folky song, but it has a spookiness to it…

IS: It was a nice acoustic song, but I didn’t want to do anything to complement it in a way that I knew how to do. I wanted to do something completely different, so I distorted the bass, and tracked it with a harmony. It gives it this backdrop – it’s almost like it’s being ripped apart behind this nice thing. It has an edgier feel.

‘I was thinking of some sort of fucked-up, arthouse ballet thing, crossed with a kung fu movie!’

The title track, which has a trippy organ sound, is an instrumental that splits the album in half…

IS: I’ve always wanted to have an instrumental on an album. It did have lyrics, but then I thought the keyboard melody was so strong… It reminds me of Queen St. Gang by Arzachel.

Have you ever heard that? It’s like an organ-led tune, and I’ve always wanted to do a track like that. Once we got the organ on, I was like, ‘Let’s just make that the feature…’ and I just jibbed off the lyrics.

Where did the title, Lotus and the Butterfly, come from?

IS: It’s a bit pompous, but I was thinking of a Stravinsky record or Madame Butterfly, or a ballet or a play. Some sort of fucked-up, arthouse ballet thing, crossed with a kung fu movie! It just sounded good to me. When Nick sent back what he’d written, I said that the two characters in the story should called be called Lotus and the Butterfly.

Sugar Re is one of my favourite songs on the album, and it stands out because it has a country-rock feel. It’s more like something off Drifter’s Skyline…

IS: I’ve had that song for a long time, and I could never quite get the right spin on it. When I was first doing the live stuff for Cut from a Star, it was more like a Moby Grape track… It’s now kind of got a feel like The Band – we’ve got a clavi on it. I was thinking, ‘What would The Band do on this?’

I really like Tulip Morning too – it has a haunting, ‘60s folk song vibe and sounds like something from a film. There’s almost a traditional feel to it…

IS: I watched the film Barry Lyndon by Kubrick. I’d put it off for years, because I’ve always had a thing where I’ve hated period dramas, and it looked like one of those, but then I thought, ‘Oh, I’m going to watch it because Kubrick’s brilliant…’

It was the melancholy mood of that – he [Barry Lyndon] is a bit of a wretch, and he’s a liar and a blagger. He works his way up and he marries into wealth, but he’s getting it on with all the maids. The lady of the house falls into a deep melancholy and I wanted to capture that in a song. It kind of came out a bit sort of Syd Barrett in a way – like Jugband Blues.

You’ve covered a song by The Coral on the album – Roving Jewel, from Butterfly House, and it’s quite different. You’ve made it more psychedelic…

IS: That’s the only track on the album that I regret not doing slower and with more picking, but the album was done… There’s a track on Sea of Mirrors called The Way You Are, which is my song. It was on Lotus and the Butterfly, and then Nick said to James, ‘Oh, we’ve got to put this on the Coral album,’ and I thought, ‘Oh, well – more people will hear it if it’s on there…’

So, I took it off my album and I was in a position where I needed another song. Roving Jewel was one that I wrote with James years ago – I used to do it when I did solo acoustic gigs. I put down the acoustic and then me and Molloy just jammed the bass and the drums. It felt good, and it’s something for Coral fans – a different version. The original’s quite layered-up and it’s got that No Other [Gene Clark] production on it, with tracked acoustics. I wanted to do a rawer, more stripped-back version of it.

I like the psychedelic guitar freak-out at the end…

IS: Yeah – it’s got that sort of Love thing, but I wanted it to be like John Wesley Harding [Bob Dylan album] too. I didn’t want too much guitar on it until that section, so you could get more drums on it.

The album finishes with Rolling In The Ocean, which is a calmer and more gentle song – it’s a sweeter and more positive note to end the record on. There’s less melancholy rage…

IS: Yeah. There’s maybe a glimmer of hope (laughs).

Are you planning on doing any solo gigs to support the album?

IS: I’ve spoken to The Dream Machine – they might jump on live with me. I’m looking at doing a one-off gig in Liverpool in April, and maybe something in London… I’ll see how it goes. It’s tricky now, as it costs so much to get out on the road.

It’s tough at the moment for acts and small to medium-sized venues, isn’t it? What’s the grassroots music scene in Liverpool like?

IS: I’m not sure, because I’m not really in the scene any more. When I’m speaking to people, like promoters, they say that tickets aren’t selling like they used to. I don’t know if music’s getting worse or it might be the cost of living crisis…

‘I’m not prepared, and neither are The Coral, to do the gross shit that you have to do… We’re still true to the art. A lot of people I know will figure out algorithms and write a song to get on a playlist – it’s like a business’

Some people can’t afford to go out to gigs, yet you’ll get people who will buy Glastonbury tickets without knowing who is on the line-up… There’s a real polarisation…

IS: Yeah, it’s crazy. I think the Tory government has just fucked the country, and there are things like Spotify and the things that you have to do…. I’m not prepared, and neither are The Coral, to do the gross shit that you have to do… We’re still true to the art. A lot of people I know will figure out algorithms and write a song to get on a playlist – it’s like a business. I’m not from that school and I just don’t understand it.

So, are The Coral looking to take some time off after a hectic few years?

So, are The Coral looking to take some time off after a hectic few years?

IS: I’m always up for working, but I think our James wants to take a little bit of downtime, after doing a double album and then the last two records, which were basically a double album and came out at the same time. He wants to get a bit of space.

The Coral are playing some festivals over the summer and you’re supporting Richard Hawley in Sheffield this August. I’ve always thought a Hawley and Coral collaboration could be good – he likes Scott Walker and Lee Hazlewood, as does James…

IS: Yeah – I’ve only met him once. He came to meet us in Sheffield, and we just talked about The Everly Brothers for about two hours.

Lotus and the Butterfly is released on March 29 (AV8 Records).

For live dates by The Coral, click here.