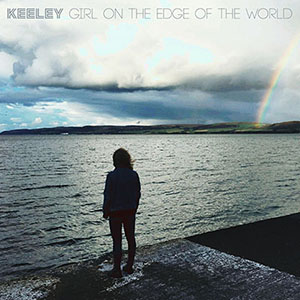

Girl On The Edge Of The World is the third full-length album from KEELEY – the Anglo-Irish indie-rock trio fronted by Dublin-born singer-songwriter and guitarist, Keeley Moss.

Like all of KEELEY’s musical output, it’s inspired by the tragic case of 18-year-old German backpacker, Inga Maria Hauser, who was murdered in Northern Ireland, in 1988 – no one has ever been charged with her killing.

Produced by Alan Maguire, Girl On The Edge Of The World is a concept album – a sonic travelogue set in the hazy spring days of 1988, in the last week of Hauser’s life, as she was travelling from Germany to Northern Ireland, via the Netherlands, England and Scotland – and it’s also KEELEY’s most expansive record yet, embracing shoegaze, dream pop, psychedelia, electronica, post-punk and indie rock.

Guesting on the record are ’90s indie legends, Miki Berenyi (Lush, Piroshka, Miki Berenyi Trio), and Sice (The Boo Radleys), as well as bassist Lukey Foxtrot and former Morrissey drummer, Andrew Paresi.

In an exclusive interview with Say It With Garage Flowers, Moss tells us about the concept behind the album, shares how and why Hauser’s sad story has affected and inspired her so much, and explains how she’s finally managed to nail the guitar sound she always dreamt of.

Let’s talk about the new album – it’s your biggest-sounding record yet. Did you consciously set out to make a more ambitious album, or was it more organic than that?

Keeley Moss: It was more organic – if you trace the progression from our debut mini-album, Drawn To The Flame which came out back in 2022, you can see the arc sonically and in terms of the expansiveness of the sound.

Over the course of our first full-length album, which was Floating Above Everything Else, in 2023, and then Beautiful Mysterious, our second album, in 2024, and then the new album, it’s been a very logical and natural progression.

One of the good things is that for an indie artist like me, who is staunchly independently minded, I would find it anathema to have that age-old scenario of a record label trying to impose restrictions or clamp down on my vision.

The fact that there is no longer that degree of corporate interference in the modern world is very much a positive thing, and because everything takes so much longer now than it used to, you can develop without being jolted by overnight success. Overnight success is no longer possible – it’s a very steady, painstaking and patient climb.

‘I would find it anathema to have that age-old scenario of a record label trying to impose restrictions or clamp down on my vision’

That instantaneous rise or catapulting to prominence, fame or wider recognition overnight, simply just doesn’t happen anymore. Although there are negatives to that, one of the positives is that you can build your musical world pretty much unbothered and undisturbed by outside forces, because there isn’t too much of a vested interest from anyone other than those that are within our team, and who are very much on board with what we’re trying to achieve.

So, yeah – it [the bigger sound of the new album] was definitely something that came about naturally. I characterise it as being like this: anyone who liked our first album will love our second album, and anyone who loved our second album will, hopefully, adore our third album, because it is very much a natural development or continuation of what we’ve been about.

In the press material for the new album, it says that this is the first time you’ve managed to capture the sound that was in your head on record. Can you elaborate on that?

Well, what I meant by that is that this is the first time we’ve managed to capture the ‘sonic swirl’ – that’s a particular word that I use to describe specific guitar sounds.

There’s a sound that I’ve captured on this record, in conjunction with our producer, Alan, who helped me to realise that goal. There’s a particular guitar sound that I’ve been chasing for years, and I finally captured it and managed to record it on this album.

You’ll hear it on the first track on the record, which is Hungry For The Prize, and you’ll hear it on a song called Fell In Love With A Ghost, which is track 10.

You’ll also hear it on the title track, Girl On The Edge Of The World – it’s where you get this very atmospheric, swirling, kind of cavernous guitar tone. It’s a sound I love and when I finally captured it, it was a real eureka moment in the studio.

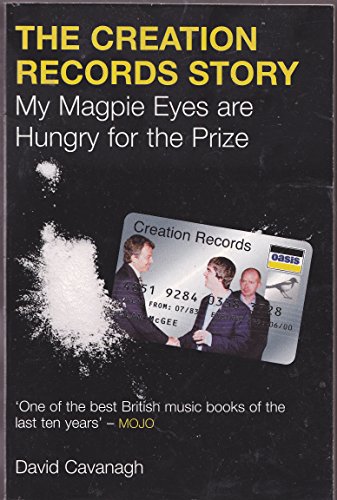

You mentioned Hungry For The Prize, which opens the album. There’s a line in that song which says: ‘My magpie eyes are hungry for the prize.’ Being an indie geek, I recognised the lyric from a song by The Loft called Up The Hill and Down The Slope, and it’s also the title of David Cavanagh’s book on the history of Creation Records…

You’re spot on – it’s a knowing nod to the late, great David Cavanagh. That book, The Creation Records Story: My Magpie Eyes Are Hungry For The Prize, is the best book on the music biz I’ve ever read – it’s my Bible. It’s absolutely riveting, and, until I read that book, I wasn’t aware of the song Up The Hill and Down The Slope.

It was the perfect title [for the book] because obviously the Creation Records story is very much one of aspiration and hunger, and a drive and the will to succeed and to create an amazing stable [of acts] and an amazing indie label that would be able to go to battle with the corporate behemoths.

It’s about having indie values and making records which would stand the test of time, which those great Creation records obviously do. If anyone hasn’t read that book, I would urge them to. It’s for anyone who’s a fan of any of those great Creation bands, from Primal Scream to Oasis, My Bloody Valentine, Super Furry Animals, Teenage Fanclub, The House of Love… It covers the entire arc of Creation’s lifespan.

Like all your other records, the new album was inspired by the tragic death of 18-year-old German backpacker, Inga Maria Hauser, who was murdered in Northern Ireland, in 1988. How did you first become interested in her story?

I’ve always had a deep interest in true crime, ever since I was a child. I’d read a brief passing reference to Inga in a book by an Irish crime correspondent and crime author called Barry Cummins, back in the 2000s.

He said she had been abducted or gone missing after a ferry journey from Stranraer to Larne, and it just kind of piqued my interest, but not enough to delve deeply… I remember thinking, ‘That’s curious, because those are two places that you don’t really hear spoken about’ – they’re not like New York or London. They are two places that there’s not an awful lot of media stories emanating from.

Many years after that, I was reading a book called Missing, Presumed, which was written by a guy called Alan Bailey, who had been in the Garda Síochána [police force in the Republic of Ireland]. He was the national coordinator for a think tank called Operation Trace, which was devised to investigate potential links between six specific missing persons cases involving young women in the county of Leinster in the 1990s – from 1993 up to ’98.

Over the course of that investigation, the remit was widened to include other cases which may or not have been connected – to try and establish if there were links with other cases from prior to that time. Criminal profilers were enlisted by Operation Trace to make suggestions, and one of those suggestions was to have a look at the case of Inga Maria Hauser, who was murdered in 1988.

It predated the think tank by five years and was outside of the geographical area – Inga’s abduction and murder had taken place in County Antrim – but it did involve a reinvestigation of her case, as part of Operation Trace.

After the national coordinator had retired and after Operation Trace was wound up, he wrote a book about his career. Towards the back of the book was a short chapter on Inga’s case, and, after reading about her story, it was like an arrow into my brain… There was a sudden and striking uprising within me that I couldn’t shake loose.

I was working in a library at the time, and I would get up in the morning and think about Inga’s story on my way to work. It was also on my mind throughout the day and after I finished my shift.

So, after a number of weeks, I tried to find an outlet for that energy and that fixation. I decided I would try and write a blog because I’d looked online to try and learn more about Inga, but there was very little about her – just the bare facts of the case. Who was she? Why had she been in such unusual locations?

‘Reading about Inga’s story was like an arrow into my brain…There was a sudden and striking uprising within me that I couldn’t shake loose’

I realised that in order to write about it properly, I was going to have to research it in depth, which I did for four months. And then I wrote part one of what became The Keeley Chronicles, which was a blog that I founded. I posted it online, and to my amazement, it went viral.

I didn’t even think it was a possibility, and I wasn’t ready for the impact that it would have, in terms of me being inundated with emails and inquiries from all across Europe, particularly Northern Ireland. That was what alerted me to the fact that there was a huge groundswell of interest in her case that had never come to fruition.

I felt even more impassioned about trying to help to make a positive difference in her case, because I just felt a real spiritual kinship with her. I didn’t know her personally, but it was a very curious thing. I then spent the next few years becoming more deeply involved in her case, and trying to find a way to assist the enquiry in any way I could, whilst at the same time being aware that I was coming at it from a very unusual place – I’m not a police office or a detective, I’m an indie-rock musician from Dublin.

I was quite naive about what I was getting into – especially in a place like Northern Ireland, which is a very complex environment. That added another layer of intensity and intrigue, which has gone into the songwriting. If you’re a songwriter, you write about what you’re most passionate about, and what you’re most intrigued by, or most interested in, and because her story and her life was on my mind so much, it was inevitable that that was going to seep into my songwriting.

‘I’m not a police office or a detective, I’m an indie-rock musician from Dublin’

What I didn’t expect was that it was going to become my songwriting, and that here we are now and she is still all I’ve written about for the last 10 years, which is kind of unprecedented in musical terms.

It’s like every album you’ve made is a concept album…

Exactly, and I like that. Concept albums were something that rose to prominence in the 1970s with the advent of progressive rock. I love the notion of a concept album – the thought of it being more than just a collection of songs but having a thematic link throughout. It means something more than just a selection of tunes.

Our last album, Beautiful Mysterious, was very much a concept album. The first two records we made, Drawn To The Flame and Floating Above Everything Else, are conceptual and all the songs are about aspects of Inga’s life, but there isn’t a linear arc to those, like there is with the new one and the previous one.

‘With this record, I’m sitting you on a rickety and clattering British Rail train, in the spring of 1988, and you’re seeing the grime-laden window pane…’

It’s a story that I just have to tell, and it’s coming from a pure place – no one in their right mind would sit down and go, ‘I know what I’m going to do. I’m going to make an album that deals with this very specific, unusual story and takes the listener all the way back to the spring of 1988…’

It’s something that is so unlike the kind of records that other people are making and have made, but there’s just something about that timeframe that I love, and I find it very emotional – trying to take the listener on a journey, so they can see the world through Inga’s eyes. That’s what I’m doing with this record – I’m sitting you on a rickety and clattering British Rail train, in the spring of 1988, and you’re seeing the grime-laden window pane…

All those real elements are there. It’s not a pristine window and you’re not seeing some untouchable, distant and unrecognisable land like San Francisco. You often get songwriters lapsing into Americanisms… You won’t find one Americanism on any of our records – it’s just not part of my lyrical landscape.

There are no boulevards…

Exactly.

Never mind the boulevards…

(Laughs).

The first song on the album, Hungry For The Prize, recounts the journey that Inga takes – from Germany to the Netherlands and then England. I think it captures that excitement and sense of discovery – how she’s setting out on an adventure, during her Easter college break. The album is a travelogue – how easy was it to map out that journey, write the songs and make it work in a linear fashion?

I love that you’ve asked me that because for me it’s one of the central features of the record – not just the story of it but also the story of my life over the past 10 years. It’s about trying to get as close as I can to bringing the listener and the reader of The Keeley Chronicles blog to the reality of where Inga was, what she saw, what she felt and how much those moments meant to her.

It was the last week of her life, and it was the best week of her life, if you can rely on her own diary extracts and her postcards home. It was just something I found so emotional – there she was, very much in the spring of her life, and it actually was springtime – but she was also blossoming as a person.

‘I was able to take the listener on a journey in tribute to Inga, and to try and preserve the purity of her original mission’

She was 18 years old, she was on the cusp of her entire adult life, and all the beauty and the idealism that went along with that – the joy and brightness she experienced on that week away, and then the absolute contrast with the darkness that she would encounter when she arrived in Northern Ireland. It’s such a striking dichotomy.

I was something that I got a better understanding of when I retraced her steps, back in 2018. I had four days off between my work shifts, and I had to go over to London anyway, so I bought myself a rail pass and I mapped out her journey. I learned so much during that experience – the full story of what happened on my retracing of her steps is discussed in the blog, between parts 21 and parts 34.

It gave me an insight I wouldn’t have otherwise had before I set out on that journey. I said to myself that I could read about her encounters to a certain degree, but that there was no substitute for actual lived experiences and having that empirical knowledge – what it was like to navigate that landscape and to do those journeys, on those trains and over those bridges, travelling from London to Cambridge, to Oxford and through England to Inverness, Stranraer and Larne.

While I was retracing her steps, what really stood out for me was that how little had changed in the places that she had been, over the course of 30 years. I was seeing as close to what she had seen, and that gave me an insight to be able to make the records in a more vivid and authentic way – I was able to take the listener on a journey in tribute to her, and to try and preserve the purity of her original mission.

Yes – the album is very cinematic, and in the lyrics you use a lot of imagery, like trains and places, as well as extracts from Inga’s diary and postcards.

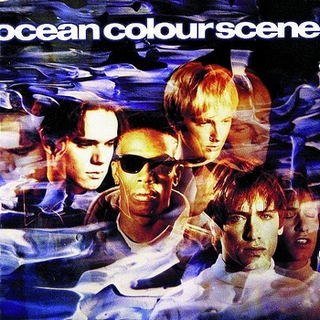

We should talk about some of the guest musicians on the album. As well as your rhythm section, Lukey Foxtrot and Andrew Paresi, playing bass and drums, respectively, you’ve got Miki Berenyi (Lush, Piroshka, Miki Berenyi Trio) and Sice (The Boo Radleys) singing on it. I know you’ve been a support act for The Boo Radleys and the Miki Berenyi Trio, and you’re a fan of both bands…

Getting to know them has been lovely, and touring with them has been amazing as well. When I first got into music in the ’90s, I would’ve heard The Boo Radleys before Lush… The first Boo Radleys record I heard was Wake Up, Boo! which I still think is one of the best pop songs of the past 30 years.

They’ve almost disowned it now..

I know – it’s a real shame. That record has oddly been mischaracterised as a sort of ditty… but there’s such a lovely melancholy to it: ‘Summer’s gone /days spent with the grass and sun…’

It definitely has a dark undercurrent, but the song got hijacked by breakfast radio shows…

I know it did. Musically, when it comes out of the middle eight with that clanging guitar tone… It’s great – it’s almost as if there’s an album’s worth of ideas in that one track. That’s the great thing about the Boos and Super Furry Animals – they were just crammed with ideas. You don’t get that so much nowadays.

I became a huge fan of the Boos and I got into Lush in the early 2000s, after they’d split up for the first time. Miki is a dear friend and I’m so proud to have her on the record. She’s got such a distinctive singing voice, and what she’s done on the track that she sings on… Anyone who loves Lush and shoegaze will hopefully bask in the beauty of what she’s managed to create, and in what Sice has managed to add to our track. Those two songs – Trains and Daydreams and Big Brown Eyes – are earmarked to be future singles, so hopefully they’ll get more focus.

Trains and Daydreams is one of my favourite songs on the album – it has some great psychedelic, jangly guitar on it…

Yeah – when I wrote it, there was a kind of lingering melancholy to it and we’ve managed to emphasise that in the recording. It was so lovely to have Sice on it. I met him for the first time at a gig in Dublin, and we just instantly clicked – he’s such a lovely fellow.

The Boos were so lovely to us – they took us on the road with them. I feel so honoured to have had the opportunity to support not only The Boo Radleys and the Miki Berenyi Trio, but also Echobelly, Terrorvision, The Primitives, Northside… There are lots of bands that have taken us under their wing, and it’s been amazing. Their audiences have been really receptive to us.

The last few songs on the new album reflect on what’s happened since Inga died. Fell In Love With A Ghost is about trying to find the answers to what went on and The Movie of Our Yesterdays is more personal – it deals with how you feel about singing about Inga:‘I sing to you alone, knowing we can never meet, knowing you can never know…’

If Inga was still alive, what do you think she would think about what you’ve done for her? I know that sounds strange because you wouldn’t have written about her if she hadn’t have been murdered, but you know what I mean…

It’s a really interesting viewpoint: what would she make of it all? I’ve asked myself that question so many times. I hope she’d be flattered, and I think she’d be surprised. When you embark on a project of this nature, which simply hasn’t been attempted before… It’s one thing to write a song about someone and their life, but it’s another thing to write an album about them, and it’s another thing altogether to write an entire discography.

Given that there are very few, or comparatively few, examples of Inga’s writings, and evidence of the life that she left behind, it’s quite an undertaking to be able to find new angles to write about her over the course of what is effectively now four albums. I’ve managed to do that somehow, but, with this new album, in particular, what I love about it more than anything else is that it focuses on the aspect of the story that has always been the most interesting for me, right from day one – and that is the time when she was most alive, which was the last week of her life.

‘It’s one thing to write a song about someone and their life, but it’s another thing altogether to write an entire discography about them’

It’s probably the ultimate tribute to her, in that it’s a record that is primarily concerned with with her as a living being and as a life force, and where she was… In my own small way, I can create for her…. Those who killed her, and those who have continued to defy the efforts of the authorities to bring them to justice, can’t take that away from her – it’s a measure of something that they haven’t been been able to erase.

If Inga came back… it’s such an interesting thing. I’ve asked myself that question, and I love that you’ve brought it up in the interview, and that you’ve been so thoughtful to ponder it. What would she think of it, if she could come back? I’m kind of fascinated by the idea. I’d love to be able to show her the albums that she had inspired, and I’d be so intrigued to see what she would make of it. I can never know and I can never show her…

The last song on the record, Daydreams and Trains, is especially poignant because it’s set after Inga has died, and the world is carrying on without her. You sing: ‘The train left on time /Without you inside/The world you left behind/But I can’t leave you behind…’ That song feels very much like a companion piece to The Movie of Our Yesterdays...

Exactly, and I felt it was the perfect way to round off the record. There’s Trains and Daydreams earlier on the album, and then there’s Daydreams and Trains. When I wrote those two songs, I felt they should either bookend the record or certainly be on the same album.

Daydreams and Trains is the reason why the story must go on, and why I haven’t been able to let go of it. It was only after I’d recorded the song that I felt it was missing something, so I got in touch with our producer, Alan, and said: ‘I have an idea for a coda – I’ll come into the studio… Trust me…’

‘What would Inga make of it all? I’ve asked myself that question so many times. I hope she’d be flattered, and I think she’d be surprised’

That’s one of the great things about Alan – he trusts my judgement and I trust his. We’ve got a great working relationship. When I went [back] into the studio, that coda just gave the song a very uplifting and spiritual denouement: ‘Girl on the edge of the world/A shooting star evaporates.’ It’s almost like a sonic shooting star to take the record into another dimension.

So, have you got your ‘sonic swirl’ guitar effects pedals sorted for when you go out on tour this year?

I have. I’ve managed to build the perfect beast. Is that an album title by Don Henley? It’s something that I liken to trying to build the perfect array of effects pedals – it’s trying to get it calibrated so there’s just the right element of this and a pinch of that… I’m always chasing my dream soundscapes… I’ve got a sweet array of sounds and I’ll be deploying them to maximum effect on our tour.

Although none of them will sound like Don Henley…

No – definitely not, although, saying that, The Boys of Summer is an absolute tune.

Girl On The Edge of the World is released on February 20 via Definitive Gaze.

KEELEY play the following headline dates across the UK in support of the new album:

Wed Feb 18: LONDON LVLS, Hackney Wick

Thurs Feb 19: COVENTRY, Tin Music & Arts

Fri Feb 20:BRISTOL, Exchange (Basement)

Sat Feb 21: BOURNEMOUTH, The Bear Cave

Wed Feb 25: BRIGHTON, The Rossi Bar

Fri Feb 27: HUDDERSFIELD, Amped

Sat Feb 28: GLASGOW, Hug & Pint

Sun Mar 1: NEWCASTLE, Cluny 2