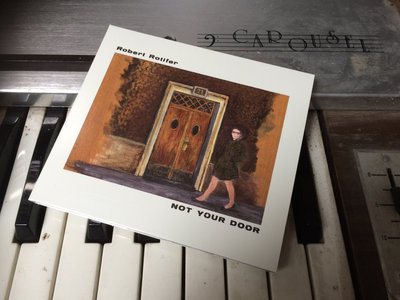

Austrian-born, Canterbury-based singer-songwriter Robert Rotifer’s new album, Not Your Door, is his most personal and autobiographical record yet, with songs about growing up in Vienna and the death of his grandmother, a Jewish communist and resistance fighter in the Second World War. I speak to him to find out why he felt the time was right to tell these stories and how they’re more relevant than ever in the current European political climate…

I’ve been listening to the new album a lot – it’s a great record…

Robert Rotifer: I’m glad and I’m grateful that you like it because I sometimes find it pretty hard going to listen to because it’s very intimate. People have been telling me they like it, but it was really hard for me to let go of some of the stuff. It’s quite intense and there are just ten songs – I felt that if I put 12 songs on it, it would’ve been too much. Also, these days, you want it to sound good on vinyl and the truth is, the less you put on there, the better it sounds.

I think it works really well on vinyl because, thematically, there are two distinct sides to the record. The first half of the album deals with contemporary subjects, including immigration and the smartphone generation, while the second half is a song cycle about you and your family’s experiences of growing up and living in Vienna.

RR: The songs on the first side give you the background to where the second side comes from. Side one should open your mind – ‘what is this guy talking about?’ – and on side two, you can see where I’m coming from. It has a dramatic curve.

I like the details in the lyrics and the stories that you tell in the songs…

RR: They’re compelling. I couldn’t take into account what people might make of it and I felt there were things that I just needed to write about, which should always be the case. I couldn’t edit myself accordingly to what was going to work with an audience, which was a real self-indulgence, but I’m aware of that.

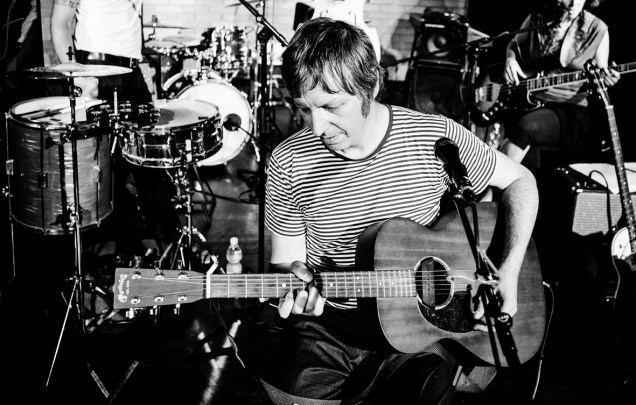

It’s arguably your most personal and autobiographical record and it’s a Robert Rotifer album, rather than one by your band, Rotifer. Although the guys from Rotifer play on the record, was it always going to be a solo album?

RR: It just happened that all sorts of things conspired – Mike Stone, who plays bass, was very busy and Ian Button (drummer) was busy with Papernut Cambridge. I just felt that I had this personal stuff to get rid of and it seemed right to do the record by myself. Mike and Ian were absolutely fine with it – there was no animosity.

Some of the songs – the title track and Irma la Douce – are about your grandmother, Irma Schwager, who died last year. She was a Jewish communist who fled Austria to escape the Nazis during the Second World War and joined the French resistance. The title track sees you standing outside her old flat in Vienna…

RR: My grandmother died when she was 95. She met my grandfather during immigration, while they were part of the underground Austrian resistance in France – they were both Jewish – not religiously so – but by birth. My mum was born in France when she was in hiding during the Second World War.

My grandparents came back to Vienna in 1945 and moved into a flat that was right next to the Danube Canal – it’s the bit of the Danube that goes right into the city of Vienna. That was one of the last strongholds where the Nazis had hidden.

When my grandparents moved in to the flat, part of the outside wall had collapsed because the Russians had lobbed grenades into the building. Until the very end, you could see bullet scars in the doors and there was a hole in the wood panelling where they’d looked for hidden weapons. After my grandmother died, my mum found pictures of German soldiers in uniform having a jolly in the flat. It had belonged to a Jewish family and was taken over by a Nazi general.

When my grandparents came back, they were offered the flat. For me, it’s a symbolic place and has more to say than just my personal history. With the way politics is going in Central Europe at the moment, I think these stories need to be told – it’s essential to explain to people was it was actually like.

On my grandmother’s 90th birthday, there was a big do, because she was a little bit of a celebrity in leftie circles. I was invited to sing and I sang a song called The Frankfurt Kitchen, which is about a kitchen design from 1928 that was the daddy of all the Ikea kitchens. It was designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, who was a friend of my grandmother’s.

I played it as a tribute to her friend, who had died, and as I was on stage and my grandmother was standing next to me, I said to her that I was glad that she came back to Vienna, otherwise I wouldn’t be here. I asked her why she’d come back and, like a shot, she said that it was because they’d won. I thought that was the best reason ever.

When she died, it became obvious to me that that idea of her coming back had gone – I can’t rely on other generations having fought for me. It was really emotional for me and I felt all these songs about Vienna coming out. While they might be about me, they also say something about where Europe – and the world – is at the moment, from Trump all the way to Nigel Farage and Norbert Hofer [the far-right Austrian presidential candidate who was narrowly defeated earlier this year].

I don’t want to get too political about it because it’s emotional for me, but it’s about feeling safe.

One of my favourite songs on the album is the opening track, If We Hadn’t Had You. It’s a very personal song that’s about your daughter and mentions an anti-war demo in Hyde Park that you took her to. Can you tell me about the background to the song?

RR: My daughter said I always writing depressing and sad stuff – she asked me to write something nice and I thought that if she’s said that, then the most obvious thing to do is to write a nice song about her. But I wanted to write a song that wasn’t mawkish.

I’ve tried to explain that parental happiness is also withdrawal from what happens around you – you’ve got the luxury of something which is so much more important… But I also wanted to make it clear that because you have kids you don’t have a higher calling. My daughter absolutely loves the song.

You’ve recorded two versions of If We Hadn’t Had You – the one on the album has a guitar solo by you, but the version you released on a EP earlier this year features a saxello solo by 80-year-old Canterbury jazz legend Tony Coe, who played on John Martyn’s classic album Solid Air. How did you get him involved?

RR: Living in Canterbury, I was aware of Tony Coe – I’d seen him play at jazz gigs. He was around in the Ronnie Scott’s scene in the ‘50s.

He says that Solid Air was just a session for him – that it wasn’t a very exciting afternoon, but, for the rest of us, it’s good enough!

I got him to play on another album that I was co-producing with Andy Lewis and at the end of the session we still had some time, so I asked him to listen to If We Hadn’t Had You, which I thought could do with some saxophone on it. He really liked the song and I loved what he did.

When I’d mixed my album I knew that, thematically, If We Hadn’t Had You had to be the first song on it, but with the sound [of the saxello], you would expect the rest of the record to have that aspect to it, but it doesn’t – it’s like opening a door to a room that you then don’t use anymore. After thinking long and hard about it, I tried a guitar solo on it and, all of a sudden, it got a different flavour that fitted the rest of the album. I decided to do an EP with the Tony Coe version on it to give credit to it and not lose it.

Let’s talk about the sound of the album. It’s pretty stripped-down in places – there’s plenty of room for the songs to breathe, with acoustic guitar, organ and horn, but then there’s also some freewheeling electric guitar, heavier sounds and some psych-pop and jazzy touches. It’s a hard record to describe and nail down – it’s almost as if the songs are led by the lyrics, rather than the music…

RR: Yes – completely.

What were you aiming for with this record?

RR: I’m a big fan of French records from the ‘60s and ‘70s – what I like about them is the way the vocals are mixed right upfront, so you can hear what Jacques Dutronc or Serge Gainsbourg is telling you. That’s the opposite of what’s happened in the mastering wars of the zero years. This was the first time I’d ever mixed a record myself and I recorded almost all of it myself.

Writing-wise what I was aiming for with this record was that I wanted to get away from that guitarist’s thing of ‘here’s four chords and let’s sing over the top’. I wanted to write it more like a piano player would. I wrote some of the songs on piano.

I’d like to ask you more about your musical influences. You moved to England from Vienna just over 19 years ago, in early 1997, but you first visited England in 1982, as a 12-year old. What music were you into when you were young?

RR: My parents sent me to Canvey Island in 1982, when I was 12. Before then, I had been terribly Anglophile. It was a formative experience – in 1982 in Essex you saw second-generation mods running around and the look was magical to me. I was such a Beatles fan as a kid and I’d got into The Kinks and The Who.

So when you were growing up in Austria, you didn’t listen to local music?

RR: There was local rock music…. The case for Austrian indigenous pop music, whatever that means, because it’s a multicultural society, is quite important for me. I’ve been the co-founder and curator of the Vienna Popfest, which is a huge thing – it’s an annual festival where tens of thousands of people turn up. It’s anything that you could possibly describe as ‘pop’, but one of the great things about Vienna is that people are very schooled in the avant-garde – they keep an ear open for music that is odd. So at the Popfest you can have people playing something that in no other place in the world would be considered pop.

I like Austrian pop music, but when I lived there, there was this thing called Austropop, which was complacent, stolid and boring pop music. There were people with horrible hairdos and DX7 keyboards… As a teenager, I tried to get away from it as much as possible.

Then there was the Austrian version of Neue Deutsche Welle – the German New Wave thing. It was a mixture of what the Germans did and Austropop, which was even more fake to me.

I sang in English and I always played in very Anglophile bands – there was a mod and ‘60s culture going on. I became a music journalist in ‘91/’92 – I was studying, but I was offered a job because I wrote an article about Billy Bragg that people liked. I then went freelance and got into radio, which I still do today.

I ended up being the Britpop correspondent – I went to festivals like Reading and Glastonbury and hung around the hospitality area. If you were accredited, you could stick a microphone in Jarvis Cocker’s direction and he would talk to you.

Your new album is being released on Gare du Nord Records – a label that you’re heavily involved with. Any other new records and projects in the pipeline?

RR: This is an exclusive. There’s a new Papernut Cambridge album already finished. One afternoon, we decided to try and organise something like The Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus – it’s called The Cambridge Circus! I’m really looking forward to that.

Robert Rotifer’s new album, Not Your Door, is released on July 1 on Gare du Nord Records – CD/LP and download. For more information, go to http://www.robertrotifer.co.uk & http://robertrotifer.bandcamp.com

The album launch party takes place on June 30 at Servant Jazz Quarters in London: tickets are available here.