From cinematic late-night soundtracks and dark disco to jangly Americana, psych-folk, melancholy orchestral pop and retro soul, Say It With Garage Flowers chooses our favourite albums of 2025 and looks at a few of them in more depth.

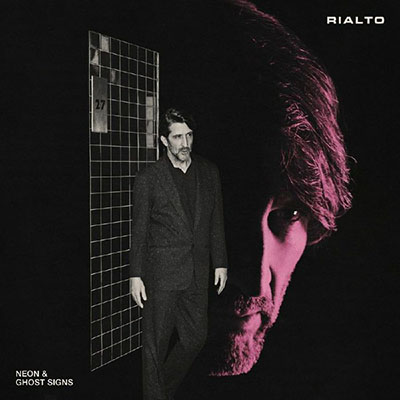

When Say It With Garage Flowers spoke to Louis Eliot, frontman and songwriter for the newly-reformed cinematic glam popsters Rialto, in early 2024, he told us that there was a possibility that the band could make a new album.

Fast forward to spring 2025 and that album, Neon & Ghost Signs – the group’s third and their first record in 24 years (!) – saw the light of day, or should that be the dark of night, as, like Rialto’s previous work, it was collection of songs inspired by night-time in the city.

“A lot of it is about searching for thrills,” says Eliot, adding: “But it’s also about heading out into the night to search for the person that you think you might’ve missed out on being… but what you find is some bruises in the morning…”

We’ve all been there… Neon & Ghost Signs is quite possibly Rialto’s finest album, and Eliot agrees, saying: “I genuinely think this album is the best one. It’s a grown-up record but perhaps not a graceful one… I know bands always love the latest thing they’ve made, but I think it’s a good album and that age has helped me write a better record.”

Well, it’s our favourite album of 2025 – a natural step on from its predecessor, 2021’s Night On Earth, which flirted with moody, Bowie-like electronica and Duran Duran-style ‘80s pop, as well as the dramatic, widescreen influences of John Barry and Ennio Morricone, which were all over Rialto’s 1998, self-titled debut album, Neon & Ghost Signs also explored new territory.

Comeback single and album opener, No One Leaves This Discotheque Alive, is a big statement of intent – over handclaps and a pounding disco groove, a lascivious Eliot is on the prowl in a nightclub, playing “the hound of London town, where the sheets are stained with gold.”

It’s like a darker, sleazier cousin of Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s Murder on the Dancefloor. The song was partly inspired by Eliot leaving behind a long-term relationship to immerse himself once more in London nightlife.

‘Rialto’s Neon & Ghost Signs was our favourite album of 2025 – a natural step on from 2021’s Night On Earth, which flirted with moody, Bowie-like electronica and Duran Duran-style ‘80s pop, as well as the dramatic, widescreen influences of John Barry and Ennio Morricone, it also explored new territory’

There’s an urgency and a celebratory feel to a lot of the songs on Neon & Ghost Signs – this is down to a near-death experience Eliot had six years ago, when he was rushed to hospital for emergency surgery while on holiday in Spain.

“What you might think is if you have a very close to death experience you want to start looking after yourself,” he says. “I just went chasing full speed after my youth. I was just like, f*** it, I might not be here next week, so I’m just going to dive in!”

I Want You is a glitter-soaked, glam rock stomp, and there’s more epic disco on the shimmering, ABBA-flavoured, Taking The Edge Off Me, with its cascading piano and soaring strings.

The edgy and European-sounding, Put You On Hold, is John Barry-meets-the-Bee-Gees, while Cherry is delicious, futuristic robo-funk that struts the same catwalk as Bowie’s Fashion.

There are some reflective moments amidst all the dancefloor shenanigans. The album’s gorgeous title track, which is cocooned in warm, pulsing synths, is a bleary-eyed, comedown ballad that’s one of the best things Eliot has ever written – an ‘us against the world’ love song, like 1998’s The Underdogs.

Sandpaper Kisses is another relationship ballad, but it’s about love gone wrong: “Sandpaper kisses, stinging on your lips. The one you want to hold in your arms is slipping from your grip.”

Eliot juxtaposes the barbed lyric with a charming and nostalgic tune that has echoes of ‘50s instrumental rock and roll duo Santo & Johnny, complete with a great, twangy guitar solo.

The atmospheric and romantic ballad, Remembering To Forget, is so beautiful that Scott Walker could’ve sung it, while second single, the glam strut of Car That Never Comes, is another of Eliot’s songs about escaping and driving through the city under the cover of night – it can be parked alongside The Car That Took My Love Away, from 2000’s mini-album, Girl On A Train, and Drive from Night On Earth.

“I need to come up with some new ideas,” he jokes, adding: “The album wouldn’t be a Rialto record if it didn’t have the things that people liked about Rialto from the past, but there wouldn’t have been a whole lot of point doing it if I hadn’t brought new things to it.”

Here’s hoping he follows it up with a new set of songs soon and, in the meantime, please can we have vinyl reissues of the first two Rialto albums and a compilation, including all the B-sides too?

Cinematic songs played a big part on one of our other favourite albums of 2025 – The Divine Comedy’s Rainy Sunday Afternoon.

For his 13th record, singer-songwriter, Neil Hannon, returned to the grandiose, orchestral pop of previous long-players, such as Absent Friends and Victory for the Comic Muse, and came up with one of his best albums in a career that’s lasted over three decades.

Recorded in 10 days at Abbey Road and written, produced and arranged by Hannon, Rainy Sunday Afternoon, features an orchestra, brass section and choir, as well as a full band, and found him in a melancholy and reflective mood – he describes it as his ‘deep in middle age album’.

Some of the songs were influenced by some troubling moments in his life – The Last Time I Saw the Old Man concerns itself with the death of his father, who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease – as well as the current state of the world.

The stunning opening song, Achilles, has a stirring and mournful string arrangement, and was inspired by soldier and scholar Patrick Shaw-Stewart’s 1915 poem, Achilles in the Trench, which was written about his experience of Gallipoli during World War 1 – Shaw-Stewart died fighting in France in 1917.

The haunting orchestration on I Want You recalls vintage John Barry, while The Last Time I Saw the Old Man is ‘60s-Scott-Walker-meets-late-night-jazz, managing to evoke a similar doomed atmosphere to Elvis Costello’s Shipbuilding, which was covered by Robert Wyatt – Hannon cites the track as an influence on his song.

Despite all the sadness, there are some lighter moments on the album, where Hannon juxtaposes the heavy lyrical subject matter with some playful arrangements.

The delightful title track, which deals with the doom and gloom in society, and having the weight on the world on his shoulders after a fight with his partner, is Bacharach and Carole King-inspired pop, while on the breezy bossa nova of Mar-A-Lago By The Sea, Hannon imagines himself as an imprisoned Donald Trump, pining for his Palm Beach resort in Florida.

All The Pretty Lights is a gorgeous and evocative recollection of a childhood Christmas trip to London, complete with a fairground organ instrumental break, and the atmospheric and yearning ballad, The Heart Is A Lonely Hunter – it takes its title from the novel by Carson McCullers – is a beautiful song about looking for love, but also leaving the past behind, and looking to the future.

‘Despite all the sadness, there are some lighter moments on the album, where Hannon juxtaposes the heavy lyrical subject matter with some playful arrangements’

After all the soul-searching, the album ends on an optimistic and hopeful note with the pastoral Invisible Thread – the lyric centres on a parent letting go of their loved one, as they flee the nest. Fittingly, the track features Hannon’s daughter, Willow, on guest vocals.

Pastoral influences were all over The Instant Garden – the debut album by Blow Monkeys frontman, Dr Robert, and singer-songwriter/ guitarist, Matt Deighton (Mother Earth, Oasis), but it’s not the first time these two talented musicians have collaborated – they worked on the Monks Road Social project, which was overseen by Robert and spawned four albums, one of which featured Paul Weller.

The pair bonded over a mutual love of Tyrannosaurus Rex – they both grew up listening to A Beard of Stars – as well as Fred Neil, Davy Graham, and Nick Drake, which shines through on The Instant Garden – stripped-back, psych-folk, with open-tuned acoustic guitar and impressive and inventive electric playing is very much the order of the day.

Robert and Deighton share lead vocals, as well as acoustic guitar duties and percussion, but Deighton takes care of all the electric guitar work.

The album was recorded and mixed in five days, at Penhesgyn Hall Studio, Anglesey, in North Wales.

Dr Robert takes lead vocals on the soulful and anthemic, Giving Up The Ghost, which brings to mind early Bowie, and he’s also the main singer on Gardening In The Mediterranean Way, which could’ve been inspired by his botanical pursuits at home in Spain – he lives in the mountains, in Andalusia.

There are more green-fingered antics on the title track, with its slow, bluesy-psych groove – it’s like a stripped-back take on Marc Bolan’s Hippy Gumbo, with Robert literally leading us down the garden path: ‘Won’t you come along with me into the instant garden? Won’t you accompany me down in the undergrowth?’

Things take a country turn on the delightful Philosophy, with Robert finding peace in a haven by the sea, and the mesmerising, acoustic-led shuffle, Supernatural Seas, which is sung by Deighton, is a magical and mystical trip – ‘I’m away from the poison breeze / High above supernatural seas’ – with a killer electric guitar break.

The spiralling Endless Circle is a bewitching and autumnal folk ballad written and sung by Deighton that has shades of Paul Weller and Nick Drake, but the Bolan boogie of the playful Superstitious Woman lightens the mood, as Robert tells us how the song’s female protagonist is trying to blow his mind.

‘The spiralling Endless Circle is a bewitching and autumnal folk ballad written and sung by Deighton that has shades of Paul Weller and Nick Drake’

Album closer, Crying Like A Child is one of the record’s more soulful and left-field moments, with Robert repeating the title phrase against a backdrop of guitars – acoustic strumming and some psych-tinged, FX-laden electric work.

It’s a wonderful record – intimate and pastoral, with a sense of mystery and exoticism. Let’s call it a garden of earthly delights – there’s plenty to dig here…

This year was a strong one for Americana records – one of our favourites snuck out just before the end of the year: Faith In Us by singer-songwriter, guitarist and producer, Tony Poole, who was a member of ‘70s English rock band Starry Eyed and Laughing, who were often labelled ‘the British Byrds’, due to their jangly sound – Poole is a wizard with a 12-string electric Rickenbacker.

This year was a strong one for Americana records – one of our favourites snuck out just before the end of the year: Faith In Us by singer-songwriter, guitarist and producer, Tony Poole, who was a member of ‘70s English rock band Starry Eyed and Laughing, who were often labelled ‘the British Byrds’, due to their jangly sound – Poole is a wizard with a 12-string electric Rickenbacker.

Poole, who is also one third of Americana trio, Bennett Wilson Poole, released his first ever solo album in late 2025.

Self-produced, it opens with the chiming and existential title track – Poole’s Rickenbacker rings clear and true – a life-affirming and beautiful song about believing in the good in humanity: “If we don’t have faith in us, what is anything worth? If we don’t begin from trust, we’re just some dust blowing round this Earth.”

Next up we’re in lighter territory – on the jaunty and groovy guitar pop of Chelsea Girls (1965), Poole finds himself transported back in time to London’s King’s Road in the Swinging Sixties.

While riding on a No.11 bus heading to Sloane Square, he contemplates how great it is to be alive in 1965, but, with prior knowledge of what lies ahead, he warns of the death of the peace and love era in ’69, and the impending Vietnam War.

It’s a fun and infectious song – Twiggy gets a namecheck, as does the Ready Steady Go! TV show and its host, Cathy McGowan – and it climaxes with a ‘60s psychedelic rock freak out.

The soaring This Slice of Time takes us back to the present day – in a moody and powerful song, which was inspired by a demo Poole was sent by US musician, Nelson Bragg (Brian Wilson), we hear how the Amazon Rainforest is being burned to raise cattle to turn into burgers.

Social and political issues also get a look-in on the brooding Imagine This – specifically the suffering caused to immigrants by Trump’s policy on the U.S.-Mexico border.

The track opens with an ominous psychedelic drone and tribal drums and then heads skywards, driven by Poole’s shimmering Rickenbacker.

There’s a touch of Beatles psych and the sound of the chaos theory butterfly flapping its wings on the anthemic jangle rock of Marcie Dancing (On A Butterfly’s Wings) – musically it’s joyous, but the song comes with a warning: “If everybody’s waiting for everybody else to come and save the world, we’ll still be waiting when it’s too late and we’re past the point of no return …”

‘The track opens with an ominous psychedelic drone and tribal drums and then heads skywards, driven by Poole’s shimmering Rickenbacker’

There’s a cinematic feel to Love or Something, which has a different vibe to most of the other tracks – atmospheric ‘80s synths create a ghostly atmosphere on a late-night, jazz-infused song that’s set on the neon-soaked streets of Copenhagen.

Album closer, Film Noir clocks in at just over six minutes – a magnificent and mysterious, Neil Young-style psych-rock epic.

Faith In Us is currently only available on CD – you can order it online at www.starryeyedandlaughing.com – but there are plans for a deluxe double vinyl version in 2026, depending on demand.

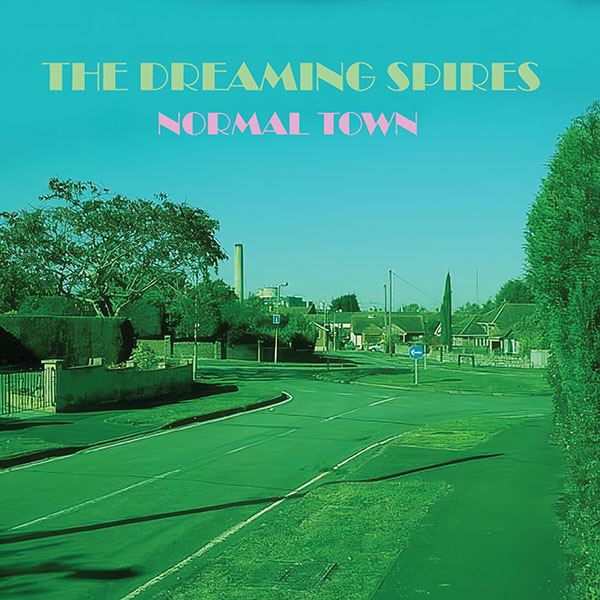

One of the other members of Bennett Wilson Poole released a great Americana album this year – Robin Bennett, who, along with his brother, Joe, plus Jamie Dawson (drums), Tom Collison (keys) and Nick Fowler (guitar) – make up The Dreaming Spires.

Their third album, Normal Town, explored themes of home, nostalgia, alienation, escapism and the beauty – and drudgery – of the everyday.

The sublime, nostalgic and atmospheric title track, which was also the first single, pays homage to their hometown of Didcot, which, in 2017, was deemed “the most normal town in England” by a bunch of number-crunching researchers.

“I don’t want to die in a normal town,” pleads Robin Bennett, over plaintive piano and cinematic twangy guitar.

‘Normal Town is less jangly than their previous albums – no 12-string Rickenbackers were used during the making of this record’

Didcot is also referenced in Cooling Towers – a reflective, bass-driven, country-tinged song inspired by the town’s power station, which was a famous landmark, until it was finally demolished in 2020.

Less jangly than their previous albums – no 12-string Rickenbackers were used during the making of this record – Normal Town has anthemic and political, Who-like power-rock (Normalisation), which sounds like Big Star covering Baba O’Riley; the Springsteen-esque crime story Stolen Car; 21st Century Light Industrial – imagine the observational songwriting of Fountains of Wayne but transplanted from New York to a business park in Oxfordshire – the folky travelling song, Coming Home, and the spacey psychedelia of Where I’m Calling From, which is a message beamed in from the future.

“It’s quite a nostalgic album – a lot of the time period I’m talking about is as much about 25 years ago as it is about now,” says Robin Bennett. “You can get to adulthood and be a bit disappointed by it – where’s the transcendent experience we were looking for?”

That’s a good question – we’ve no idea, but Normal Town is a good place to start.

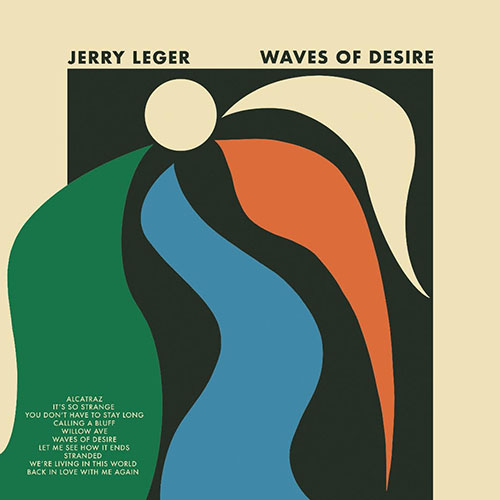

From Americana to Canadiana… This year’s Waves Of Desire, from Toronto singer-songwriter, Jerry Leger, was a mostly warm sounding set of songs, and was influenced by acts including The Beatles, The Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, and The Zombies, whose music first inspired Leger as a kid.

From Americana to Canadiana… This year’s Waves Of Desire, from Toronto singer-songwriter, Jerry Leger, was a mostly warm sounding set of songs, and was influenced by acts including The Beatles, The Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, and The Zombies, whose music first inspired Leger as a kid.

“I get a certain feeling from those songs and memories, and I wanted to try and get that same feeling with Waves Of Desire,” he says. “I’m not trying to copy or sound like those songs, but just getting close to the feeling they gave me.”

Made in Germany, during a short break from touring Europe, Waves Of Desire was recorded at Cologne’s historic Maarweg Studios, which began as an EMI studio in the 1950s and still has its main room virtually unchanged, with a mix of vintage and modern gear. Leger’s vocals were all recorded live with the band through an old German microphone.

Produced by Leger, the album features his longtime group, The Situation, (Dan Mock – bass/vocals), Kyle Sullivan – drums/vocals, and Alan Zemaitis (keys/vocals), as well as contributions from Suzan Köcher (harmony vocals) and Julian Müller (co-production / guitar).

Several of the songs make great use of close harmonies and textured analogue synths – first single, the atmospheric and ‘50s-tinged, It’s So Strange, which is a song about vulnerability and starting over, has doubled acoustic guitars, Mellotron and Everly-Brothers-style harmonies.

Album opener, the jaunty Alcatraz – written about one person leaving a relationship, while the other is left in confusion – is driven by some superb, warm Dylan-style organ. The song’s heavy subject matter is nicely juxtaposed with a breezy, poppy and uplifting backing, which Leger says was inspired by The Shangri-Las.

Let Me See How It Ends – another song influenced by the Everly Brothers –sounds like a long-lost ‘50s breakup ballad – and the organ-drenched Calling A Bluff mixes a sultry, Rolling Stones shuffle on the verses with a big power-pop chorus.

On the ethereal and haunting, We’re Living In This World, Leger envisages the protagonist floating in space – there’s tinkly piano and a Moog synth creates a breathing effect, which adds to the feeling of disconnection: ‘You’re living in this world/ I’m in the twilight zone,’ sings Leger.

Stranded is another song about isolation – Zemaitis plays a spacey synth solo, which heightens the mood – and on the nostalgic and partly autobiographical, Willow Ave, Leger reminisces about childhood walks with his father around Toronto’s East End.

‘On the ethereal and haunting, We’re Living In This World, Leger envisages the protagonist floating in space – there’s tinkly piano and a Moog synth creates a breathing effect, which adds to the feeling of disconnection’

The title track is an upbeat rocker, and the album ends with the reflective, piano-led ballad, Back In Love With Me Again, which opens with the lines: ‘Another day older, another job done…’

It’s been 20 years since Leger’s first solo album – 2005’s Jerry Leger & the Situation. Waves Of Desire sees the start of a new partnership with Hamburg-based label, DevilDuck Records, and next year he will be touring the UK to support the release.

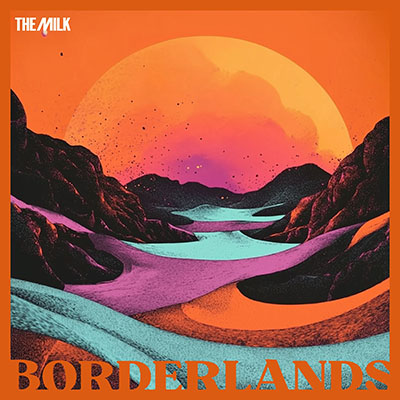

Leger is a fan of vintage soul music, so he’ll probably dig this year’s album by Essex-based band The Milk.

Borderlands, which was influenced by acts including Brian Wilson, Paul McCartney, Miles Davis and Michael Kiwanuka, is the group’s most ambitious and fully realised record yet – a stunning set of cinematic soul songs.

It’s a melting pot of ‘60s and ‘70s-style soul, modern funk and jazz, and vintage film soundtracks.

Like all the best records, the album takes you on an emotional journey and is designed to be listened to in one sitting – it’s a coherent piece of work that starts with the striking and filmic I Need Your Love and closes with the epic love song, I Saved My Best For You, with its silver screen strings.

“We’re very much into making a body of songs that has a beginning, a middle and an end – that’s how I listen to music at home,” says Rick Nunn, the band’s vocalist and keys player.

‘Like all the best records, the album takes you on an emotional journey and is designed to be listened to in one sitting – it’s a coherent piece of work that starts with the striking and filmic I Need Your Love and closes with the epic love song, I Saved My Best For You, with its silver screen strings’

“I like the commitment of putting a record on and then having 40 or 45 minutes when I don’t need to make another decision.”

He adds: “People who like soul music will hopefully like it, but we also just wanted to make something that was a talking point in itself – even if it’s not your thing, it’s a big-sounding record.”

“We spent about a year arguing about the references and batting ideas around, and eventually we all gave in and said, ‘Let’s make something huge.’”

Nunn explains how very few bands have got the resources or the budget to make a high-production, mid-‘70s soul record, but that having their own studio allows the group to have more time and creative freedom, and lets them achieve their ambitions without costing a fortune.

It’s a move that’s certainly paid off – with Borderlands, The Milk men well and truly delivered.

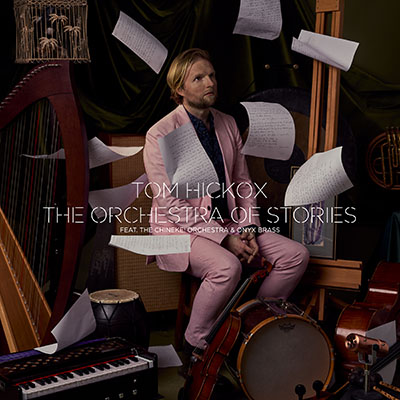

Sounding huge was something that baritone-voiced singer-songwriter and pianist, Tom Hickox, achieved on his long-awaited third album, The Orchestra of Stories.

A grandiose affair, inspired by the lush, dramatic and mysterious sound of Scott Walker’s seminal solo albums of the late ’60s, The Orchestra of Stories is a stunning piece of work – a set of largely story-based songs on which the London-based Hickox collaborated with the Chineke! Orchestra – Europe’s first majority black and ethnically diverse orchestra – and the Onyx Brass ensemble, as well as guitarist, Shez Sheridan, from Richard Hawley’s band.

As if that wasn’t adventurous enough, Hickox produced the album himself, which was a first for him.

“It wasn’t initially my intention to produce it myself,” he says. “I co-produced my first one with Colin Elliot, who works with Richard Hawley, and I produced the last one with a bassist friend of mine called Chris Hill.

“I really enjoy collaborating, because, otherwise, it’s quite lonely, but I met up with a couple of people and talked to them about doing this record, but nothing clicked, so I just started getting on with it myself.”

‘The Orchestra of Stories is a stunning piece of work – a set of largely story-based songs on which Hickox collaborated with the Chineke! Orchestra and the Onyx Brass ensemble, as well as guitarist, Shez Sheridan, from Richard Hawley’s band’

He adds: “As I started getting into it, I realised quite soon it was my vision and that I had to do it because of the way it was forming. It’s a massive production and it took a long time to get together – it required lots of different studios, lots of musicians and lots of money!”

The orchestral arrangements were recorded in London’s AIR Studios, while other parts, including vocals, drums, bass, piano and guitar, were laid down in studios in North and South London and Sheffield.

Opening song, The Clairvoyant, inspired by a tragic tale of a man in the US, who was hustled out of his entire life savings and house by a fraudulent psychic, is the perfect scene setter – Mariachi brass gives way to a piano and Hickox’s deep and rich croon, before a moody string arrangement creeps in and then unfolds. The effect is startling and unsettling – a very powerful start to the record.

The gorgeous Chalk Giants has a lighter touch, with acoustic guitar, stately strings and pastoral horns – the song finds Hickox on a bucolic English road trip, searching for greater meaning in life.

The serene mood doesn’t last for long, though… Chalk Giants is followed by the dark, brooding and satirical Game Show, with its sleazy, James Bond horns, filmic strings and news audio clips recorded by CNN’s Clarissa Ward, BBC’s Nick Beake and the actor, Rory Kinnear.

For the lyrics, Hickox took inspiration from the Cambridge Analytica and Edward Snowden personal data scandals.

On haunting album closer, The Port Quin Fishing Disaster, we are transported to a small Cornish fishing village, where a tragedy strikes during a raging storm, while in The Failed Assassination of Fidel Castro, Hickox plays the part of Marita Lorenz, who was tasked with seducing the Cuban revolutionary and putting poison in his moisturiser but ended up becoming his lover.

These stories are a gift for a talented and inventive singer-songwriter like Hickox, who has a brilliant eye – and ear – for taking curious tales and turning them into fully-realised and often epic compositions.

In 2024, our favourite album of the year was Good Grief by Bernard Butler and this year he contributed to another record we loved – the self-titled debut album by supergroup Butler, Blake and Grant, on which he was joined by Norman Blake (Teenage Fanclub) and James Grant (Love and Money).

In 2024, our favourite album of the year was Good Grief by Bernard Butler and this year he contributed to another record we loved – the self-titled debut album by supergroup Butler, Blake and Grant, on which he was joined by Norman Blake (Teenage Fanclub) and James Grant (Love and Money).

The trio were formed when a mutual friend in the music industry suggested they play together for a concert in rural Scotland – he had a hunch that they’d work well as a group. That led to some shows in Glasgow, as part of the Celtic Connections festival – Blake and Grant are both Scottish.

Writing and recording for it began at Blake’s home, on the banks of the River Clyde – the group were looking to capture the stripped-back vibe of their concerts, with guitars and vocal harmonies.

“We went up to Norman’s to hang out for a couple of days and see what would happen,” Butler says. “It really worked – there was no set way of doing it – we just sat around in armchairs playing, and James said, ‘I’ve got this tune…’, he started playing a song, and we joined in and started working it out together.”

‘Writing and recording for the album began at Blake’s home, on the banks of the River Clyde – the group were looking to capture the stripped-back vibe of their concerts, with guitars and vocal harmonies’

He adds: “I asked Norman if he had any recording gear and he did, so we got out some mics and set them up in his living room – we had no headphones or isolation. There was no studio set up – just three microphones plugged into a computer. We said we would record everything we did – just press record and leave it. We did a song by James and one of Norman’s, then I wrote something quickly, overnight.”

There were more sessions at Blake’s place, and then Butler took the recordings to his studio in London, where he added overdubs and mixed the tracks.

First single and album opener, Bring An End, which started out as a fragment of an idea on Blake’s phone, is a good indication of what’s to follow – a gorgeous and intimate, autumnal folk song with acoustic strumming, some delightful harmonies, and Butler playing some impressive and inventive electric guitar.

It’s followed by the sublime, One And One Is Two, which is steeped in the chiming folk-rock sound of The Byrds, and was the first song the trio worked on together.

Butler takes lead vocals on his own composition, The 90s, a wry commentary on his past – “We’ve been loving the 90s for far too long”, which is a jaunty tune with a retro-soul feel, thanks to its strings, Blake and Grant’s backing vocals, handclaps and some neat, ‘70s-style guitar work.

The Old Mortality – another of Butler’s songs – is one of the record’s moodier moments. It’s a dramatic and atmospheric track, with swelling violin by Sally Herbert, and would’ve fitted well on Butler’s Good Grief.

Butler, Blake and Grant will more than likely attract comparisons to Crosby, Stills & Nash, and they channel that on Grant’s, laidback harmony-laden Seemed She Always Knew, which was inspired by Joni Mitchell and has echoes of Laurel Canyon running through it.

As you would expect from the coming together of three such talented musicians, Butler, Blake and Grant is a strong album of well-crafted songs that has an authentic and traditional charm to it. Let’s hope they make another record soon.

One of the other most inspired collaborations of the year was 84-year-old Canadian folk singer, Bonnie Dobson, teaming up with London’s cosmic cowboys, The Hanging Stars, to make a brand-new, eight-track album, Dreams. It was a match made in heaven – you could say it was as if the Stars had aligned…

Dobson’s gorgeous and haunting voice is perfectly complemented by the band’s shimmering, psychedelic Americana sound, like on the first single and album opener, the sublime and hazy Baby’s Got The Blues.

It’s followed by the fun and upbeat, country-tinged Trouble, which recalls ‘60s Nancy Sinatra. In the song, Dobson has a chance encounter with a guy in a club, is attracted to him, but knows trouble when she sees it: “One, two, three, and four, what are you waiting for? Five, six, and seven, eight, come on darling, don’t make me wait.”

On the moody Don’t Look Down there’s more trouble brewing – we’re taken on a trip into the desert for a Spaghetti Western soundtrack, with Mariachi horns and twangy guitar.

On A Morning Like This also has a cinematic vibe. With its lush, ‘60s-style strings – played on a Solina String Ensemble synthesizer – and guest vocals by Hanging Stars frontman, Richard Olson, it evokes the wonderful and slightly spooky-psych pop of Nancy and Lee.

There’s yet more drama on the stunning You Don’t Know, with finger-picked acoustic guitar, French horn and wintry orchestration, it feels haunted by the ghost of Eleanor Rigby.

Friends and family play a big part in the lyrics of the album’s reflective title track, which has Dobson, who lives in the UK, dreaming of Canada, but also singing about walking in Somerset and the hills of Shropshire: “You always can go home again, but you never can go back.”

It’s a truly beautiful and moving song, and, like the rest of the record, the stuff that dreams are made of.

Finally, it would be remiss of me not to mention an album that I contributed to this year – Document by Liverpool singer-songwriter, Edgar Jones.

Finally, it would be remiss of me not to mention an album that I contributed to this year – Document by Liverpool singer-songwriter, Edgar Jones.

I was delighted to be asked by the label AV8 Records to write the sleeve notes for it, based on an interview I did with Jones.

His 2023 album, Reflections of a Soul Dimension, was a lavish affair, with strings and brass, and influences including Burt Bacharach and Scott Walker, as well as Motown and Northern Soul, but Document is just him, in a stripped-down style, with a guitar and pedals, captured live to tape.

Based on his current live set, it’s a blistering, soulful and raw-sounding record, with covers, new versions of some old Jones classics, and blueprints for songs that will end up on his future albums.

Talking about the idea behind it, Jones says: “I don’t sit there and think, ‘Hmmm – what’s my next project going to be?’ I already had two projects on the go – one was a follow up to Reflections of a Soul Dimension called Representations, on Stereopar Records. I’d written all these songs for it and done the demos, building up the rhythm arrangements on which the strings would be added.

‘Based on his current live set, it’s a blistering, soulful and raw-sounding record, with covers, new versions of some old Jones classics, and blueprints for songs that will end up on his future albums’

“With Reflections of a Soul Dimension, I was lucky to catch Steve Parry, the producer and arranger, during some downtime in lockdown – he’s a very busy man – but we still can’t find a window to do the follow up. The incentive is there and so is the love for the project, but it’s about finding the time… It can’t be made cheaply.”

He adds: “AV8 Records had been saying to me for years, ‘Let’s do a project’, and I said, ‘Yeah – when I’ve got something…’ It turned out that I did get something – and, again, it was soul music…

“It’s a kind of a vanity project – mid-‘60s Motown stuff. I’m pretending to be a vocal group called the 4Tastics. It was going well, but we hit a wall – everyone in the band had something mad going on. There were personal problems, me included. It’s kind of 90% done now, but when it was 60% done, I was commiserating with [journalist] Lois Wilson, who said that while I was waiting for the two projects to take off, I should go into the studio for a day and bust out as much as I could of what I do live.

“I thought that was a great idea – I could revisit some old classics – put some new life into them, as I’ve been doing on stage – and put down some of the blueprints for Representations and the 4Tastics album.”

This year’s record, Document, is a great, er, document of where Jones is at, and we can’t wait to hear his next two albums when they’re done and dusted.

- Here’s a list of Say It With Garage Flowers’ favourite albums of 2025 and an accompanying Spotify playlist: please note, as it stands, Tony Poole’s Faith In Us and Edgar Jones’ Document are not available on Spotify.

Say It With Garage Flowers: Best Albums of 2025

- Rialto – Neon & Ghost Signs

- The Divine Comedy – Rainy Sunday Afternoon

- Tony Poole – Faith In Us

- Dr Robert & Matt Deighton – The Instant Garden

- Bonnie Dobson & The Hanging Stars – Dreams

- The Dreaming Spires – Normal Town

- Butler, Blake & Grant – Butler, Blake & Grant

- Kathryn Williams – Mystery Park

- Paul Weller – Find El Dorado

- Ron Sexsmith – Hangover Terrace

- Jerry Leger – Waves of Desire

- Tom Hickox – The Orchestra of Stories

- The Milk – Borderlands

- Andy Bell – Pinball Wanderer

- Depeche Mode – Memento Mori: Mexico City

- Johnny Marr – Look Out Live!

- Sharp Pins – Balloon Balloon Balloon

- Nelson Bragg – Mélodie de Nelson: A Pop Anthology

- Matt Berninger – Get Sunk

- Vinny Peculiar – Things Too Long Left Unsaid

- The Delines – Mr. Luck & Ms.Doom

- Patterson Hood – Exploding Trees & Airplane Screams

- Chris Eckman – The Land We Knew The Best

- Emma Swift – The Resurrection Game

- Jake Winstrom – Razzmatazz!

- Gary Louris – Dark Country

- Luke Tuchscherer – Living Through History

- Michael Robert Murphy – Chaos Magick

- Edgar Jones – Document

- Manic Street Preachers – Critical Thinking

- Suede – Antidepressants

- Doves – Constellations For The Lonely

- Miki Berenyi Trio – Tripla

- Jeff Tweedy – Twilight Override

- Matt Berry – Heard Noises

- The Loft – Everything Changes, Everything Stays The Same

- Jim Bob –Automatic

- Jim Bob – Stick

- Drink The Sea – Drink The Sea I

- Drink The Sea – Drink The Sea II

- The Clang Group – New Clang

- All Seeing Dolls – Parallel

- The Crystal Teardrop –… Is Forming

- Ian M Bailey – Lost In A Sound

- Kevin Robertson – Yellow Painted Moon

- Future Clouds and Radar – Big Weather

- Miniseries – Pilot

- Dan Raza –Wayfarer

- Dropkick – Primary Colours

- Edwyn Collins – Nation Shall Speak Unto Nation

- His Lordship – Bored Animal

- Chrissie Hynde & Pals – Duets Special

- Jerry Leger – Lucky Streak (Latent Lounge – Live From The Hanger)

- The Autumn Defense – Here and Nowhere

- Luke Haines & Peter Buck – Going Down To The River… To Blow My Mind

- The Len Price 3 – Misty Medway Magick

- GA-20 – Orphans

- The Blow Monkeys – Birdsong

- Rose City Band – Sol y Sombra

- Joe Harvey-Whyte & Bobby Lee – Last Ride

- Little Barrie & Malcolm Catto – Electric War

- Neil Young and the Chrome Hearts – Talkin To The Trees

- Star Collector – Everything Must Go!

- Montefurado – Heavy Heads