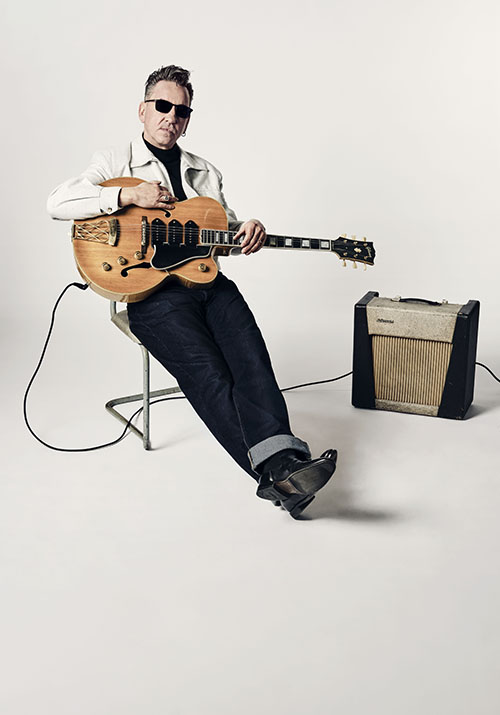

Richard Hawley‘s latest album, In This City They Call You Love, is one of the best records he’s made in a solo career that’s lasted nearly 25 years.

It’s largely a return to the sound of vintage Hawley. Heavy Rain is a beautiful, late-night melancholy ballad with strings, and Prism In Jeans recalls early Elvis and pre-Beatles, British rock ‘n’ roll, but there are also a few surprises, including soulful, gospel-doo-wop (Deep Waters), and Easy Listening bossa nova. (Do I Really Need To Know?).

Talking about the new record, the 57-year-old singer-songwriter and guitarist, says: “I’ve made three albums where I had the title before I’d even begun to record – where I had an agenda. One was Truelove’s Gutter. Another was Standing At The Sky’s Edge, when I wanted to turn everything up and make the music a lot more aggressive, and then this one.

“I wanted it to be multi-coloured in a way… focusing on the voice and what voices can do together… I deliberately only played a handful of guitar solos to keep it focused on voices, the song and space…”

Speaking to Say It With Garage Flowers in London recently, he tells us why Sheffield, the city where he was born, grew up and still lives, will always inspire his songwriting, how he ended up playing a guitar owned by Scott Walker on the new album, and why he doesn’t do social media.

He also shares his views on AI in music – “it’s fucking bollocks” – and explains how he’s tried to write songs with his friend, Paul Weller, but they just can’t make it work.

It’s almost 25 years since velvet-voiced singer-songwriter and guitarist, Richard Hawley, launched his solo career – his eponymous debut mini-album came out in 2001.

This month sees the release of his ninth studio album, In This City They Call You Love, and it’s easily up there with his best work – less heavy and psychedelic than some of his last few records, it’s mostly a return to vintage Hawley.

Heavy Rain is a gorgeous, string-soaked, ‘50s-style ballad that could’ve come off his 2005 Mercury Prize-nominated album, Coles Corner, while the country song, Hear That Lonesome Whistle Blow, has echoes of Johnny Cash and Hank Williams.

The soulful and gospel-tinged Deep Waters was inspired by doo-wop, Prism In Jeans nods its quiff to early ‘60s Elvis and pre-Beatles rock ‘n’ roll, like The Tornadoes, The Shadows and Billy Fury, and Deep Space – the heaviest song on the record– is an upbeat, crunching rocker that tackles the need for some peace and quiet – time and space – but also reflects on eco and social issues.

Elsewhere, there’s Hawley goes bossa, with the dreamy Easy Listening of Do I Really Need To Know?, the dark and menacing midnight twang of first single, the crime-ridden Two For His Heels, and the stunning album closer, ‘Tis Night’, a wintry, hymnal-like ode to spending precious moments by the fire with the one you love, that’s surely destined to appear on a lot of Christmas Spotify playlists this year – ours included.

Like a lot of Hawley’s work, the name of the album – In This City They Call You Love – was inspired by the city of Sheffield, where he was born, grew up and still lives.

The title takes its name from a lyric in the ballad People, which is one of the album’s most beautiful and stripped-down moments – in Sheffield, people refer to each other as ‘love.’

Speaking to Hawley in mid-April, at the London offices of his record company, BMG, shortly before a private acoustic gig to showcase some of the songs from the new album, Say It With Garage Flowers asks him why he keeps using Sheffield as his muse, and if that will always be the case?

“Yeah – it won’t change. That’s yer Banks in goal,” he says. “Like I’ve said before, I don’t know what it’s like to live in Bangladesh or Hong Kong, Australia or the North Pole. I’ve lived there my whole life, so why would I not use it as my muse, or whatever you want to call it. It makes the songs authentic.”

Q&A

It’s so nice to hear a song like People, which talks about a city where people call each other love – especially when there’s so much hate out there, both online and in the ‘real world…’

RH: It’s unavoidable because it’s in your face – world events and social media are influenced by each other. I don’t have anything to do with social media. I don’t know much about it, but both my sons and my daughter have said, ‘Dad – don’t… you’ll really hate it.’

When it first started, my manager’s assistant, Tilde, sent me loads of things that people were saying about me on the internet, but, obviously, she only sent me the things that were positive. I said to her, ‘I never want to see that again.’ She said, ‘Why? It’s all really nice stuff…’ It’s because I remember what my grandfather told me about reviews – he was a music hall performer, as well as a soldier and a steel worker.

He said: ‘The thing about reviews or people’s opinions is that, ultimately, they’re not really any good to you, if you’re doing something that’s creative.’ I said: ‘Why’s that?’ And he said: ‘The good ones make your head so big that you can’t get out of the door, and the bad ones make you so depressed that you don’t want to get out of bed…’

It’s nice when you get positive praise for something that you’ve put a lot of time and effort into it, but people’s opinions can’t be the be-all and end-all…

The thing I’ve observed about social media is simple – if it was an actual place – a town, a village, or a city – nobody would go. Only the nasty, crazy fucker would get on a bus, or on a plane, or a taxi to go there. Who the fuck would?

I’m not an expert on these things because I don’t do it, but, whenever the subject of social media comes up with whoever, I’ve never heard good things.

If you’d written People about London, you’ve have had to say: ‘People in this city call you a wanker…’

RH: Yeah… People in this city call you a c***!

‘The thing I’ve observed about social media is if it was an actual place – a town, a village, or a city – nobody would go. Only the nasty, crazy fucker would get on a bus, or on a plane, or a taxi to go there’

On this album, you played a guitar that belonged to Scott Walker, didn’t you?

RH: Yeah – that was a massive thing. Scott was a mate – he was someone I met when he produced Pulp’s last album, We Love Life, and, for a multitude of reasons, he and I clicked. It was to do with music, but other stuff as well – we had a certain sense of humour which both of us understood.

His manager rang up on behalf of his daughter, Lee, and the timing of it couldn’t have been more fitting… It’s a Telecaster – and she had it delivered to me three days into the recording of the record.

Didn’t you play your Dad’s Gretsch and a guitar of Duane Eddy’s on the album too?

RH: Yeah.

Duane’s one of my guitar heroes…

RH: And one of mine, and a lot of people’s… The thing about Duane is that you hear one or two notes and you know who it is – the sound is so distinctive.

Prism In Jeans, on the new album, has a pre-Beatles feel…

RH: Yeah – and mid-period Elvis stuff, like Marie’s The Name and Surrender. I’m aware that’s a nod to that, but that’s just the way it turned out.

Deep Waters reminds me of Sam Cooke – it’s soul and gospel, but with doo-wop backing vocals…

RH: What I was listening to before I started choosing the songs was the The Harmonizing Four – a gospel group. I’m obsessed with them. Are you aware of them?

I don’t know them…

RH: They go right back to the ‘30s, probably longer – they’re like The Blind Boys of Alabama in terms of their longevity, not their music. I’ve been collecting their records – most of their stuff they recorded on Vee-Jay. Their singing is phenomenal, and it definitely influenced me. I wanted lots of voices singing together – and, hey presto, half my band are fucking brilliant backing singers.

Do I Really Need To Know? is Hawley goes bossa. I love the dreamy, Easy Listening arrangement on it…

RH: Yeah – it’s got my favourite guitar solo that I’ve played on recent times on it. I used a Poltava Fuzz-Wah [pedal]. It’s weird and I bought it years ago. It’s got components that are Russian, Finnish, Ukrainian and Polish, and it’s built out of tank parts – it’s their version of trying to capture that ‘60s fuzz-wah sound, but they got it wrong, and it sounds like something completely different. It sounds more like an ARP synth than a guitar effects pedal. I also played the solos on Deep Space on that – some really crazy stuff on Scott’s guitar.

Do I Really Need To Know? could’ve been done in a reggae style or soul or bossa, or whatever… When I was doing the solo… there’s a great Bob Marley and the Wailers performance on The Old Grey Whistle Test, where they’re actually miming… They do Stir It Up, but Peter Tosh plays this guitar solo that’s absolutely fucking awesome. I love that clip and that song.

Musically, Stir It Up is actually doo-wop, but they did it in a reggae style, with the drop on the bass drum on the third beat of the bar. I love that solo and I wanted to somehow capture that vibe – I don’t know if I got anywhere close. I probably came up with something completely different or wrong, but different and wrong can be right in its own way.

Hear That Lonesome Whistle Blow is a country track – just the title makes it sound like it’s a song by Johnny Cash or Hank Williams… You like writing about trains, don’t you?

RH: It’s the language of old folk music that transferred there [the US] from the UK – English, Irish, Welsh and Scottish, as well as Gallic-French folk songs.

The landscape of America changed its scope, but the actual subject matter of a lot of the older, folk-based American songs, is trains, and the landscape and the mountains… John Henry, a figure who is ‘a steel driving man’… that’s my dad…

To me, that’s the imagery of old America, a huge part of it which enters into the great American songs, as well as songs about love, sadness and loss.

Because I’m from South Yorkshire and I’m a steel worker’s song, it immediately didn’t feel alien to me – I could identify with it straightaway, even from childhood. It’s never felt alien to me, as a Northern English man, to sing the songs that I write, because the skeleton’s the same – the components of a great American song.

There’s a lineage…

RH: Yeah – the Industrial Revolution was exported to many place…

On Deep Space, you sing: ‘It stresses it me out and it makes me ill, it always has and it always will – I need space…’ Do you suffer from claustrophobia, or are you a frustrated astronaut?

In the song you also say: ‘Oh my god, what have we done – turned our backs upon the sun, oh my Lord, where can we turn, when the earth is scorched, and people burn?

That’s about the environment, isn’t it?

RH: The thing that started me thinking about that song was a personal reflection of just needing some fucking peace and quiet, and time and space… From my perspective, as an older guy, I feel the urge for that more – I’m not interested in hanging around in large groups of shouty people anymore.

Whatever age you’re at, there are different versions of yourself, from different parts of your life, that you can no longer relate to – that’s normal. It’s about growing and changing…

There’s another component to it as well. All over the world, there’s a hideous social crime that we all allow to occur, and we all seem to be powerless to do anything about it – the increasing levels of homelessness and people who live on the street. For some of them, it’s not a happy experience – you meet people who are out of their minds on Spice or cheap, nasty alcohol…

From a kinder perspective, it also occurred to me that maybe they know something we don’t – we’re the nuts, the ones who are really crazy, because we’re the ones that are going along with this fucking society where we can sell bombs to countries that kill kids and innocent people.

‘All over the world, there’s a hideous social crime that we all allow to occur, and we all seem to be powerless to do anything about it – the increasing levels of homelessness’

There’s no chance of the homeless drunk or drug addict being invited on to Elon Musk or Richard Branson’s fucking edge of the atmosphere, space exploration [trip] for two or three hundred grand a chuck for a ticket, so there’s no chance of escaping to deep space or another planet where things are kinder and better, and people aren’t being fucking hideous to each other. The only chance they’ve got is to go inwards to a different kind of space…

The first proper book I was ever given and I read was Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea by Jules Verne. My dad gave me his copy, and I absorbed it like food. I still love Jules Verne to this day – he was a ‘time traveller’, like Leonardo da Vinci. He had such an incredible mind to conceive of all those things…

So, on the edge of our atmosphere or deep space, or a subterranean, or dark-green velvet, deep sea world in a submarine… It’s healthy to put the phone or the screen down and go and walk in a fucking park.

You have woods where you walk near your house, don’t you?

RH: I’m blessed… In Sheffield, everybody has a wood or a park near them – there are 470 municipal parks, woodlands and public spaces.

When the city was being built, and the industrialists were becoming increasingly affluent, the one thing that they did do was to provide amenities for the workforce, so they could have some kind of meaningful recreation. The legacy is that if you step out of almost any door in any part of the city, you have access to green space.

I kind of felt that was fucking normal, but if you go to Manchester, Liverpool or wherever… there’s fuck all compared to what we’ve got. To be fair, the city centre [of Sheffield] is absolutely shite – it looks like Hitler’s bombed it again.

We’ve got the oldest football club in the world [Sheffield F.C] – we invented League Football – and the other two teams that are actually in professional leagues are shite… So, there’s a lot to make you cry about being in Sheffield…

The last time I visited Sheffield, I was surprised at how much the city centre had declined…

RH: The council have absolutely fucked it. They’ve allowed all the independent businesses to disappear, or they’ve got rid of them – they’ve kicked them out because the corporate companies, like Starbucks, McDonald’s or Burger King, can pay the astronomical rents – they don’t care. Its identity as a city, in the city centre, has almost disappeared. A lot of what I do is out of frustration because I can see things slipping away from our physical grasp – it’s like holding on to water.

Coles Corner [the place in Sheffield] only existed in the minds of older people because they remembered it – ‘It was always, I’ll meet you at Coles Corner…’

‘I know I’m a songwriter and a successful musician, but I’m also mindful of the fact that I’m a husband and a father, an uncle, a brother, a son… all those different roles that you fulfil’

I do hope that in our city we don’t stop calling each other ‘love’ – a lot of people object to it. It’s not me having a go… I don’t want to harp on about the state of the world, but it is distressing that we seem to be on the precipice of something that’s not very fucking good.

You mentioned your kids earlier. I have children too – it’s worrying about what kind of world we’re leaving behind for their generation too, isn’t it?

RH: Absolutely – one hundred percent. That’s on my mind a lot. I know I’m a songwriter and a successful musician, but I’m also mindful of the fact that I’m a husband and a father, an uncle, a brother, a son… all those different roles that you fulfil.

Going back to the album… The last track, ‘Tis Night, is a magical song – it’s almost hymnal. It reminds me of when you’ve sung Silent Night live before. It’s a nice way to end the record, and it has some lovely imagery in it – growing old together, a head resting on someone’s shoulder, whiskey and firelight…

RH: Yeah. In a way, writing a song ruins the moment… It’s about those moments that me and my wife share – they’re very brief, but it’s the end of the day, the dogs are knackered because you’ve walked them… they’re asleep. You put the fire on when it’s cold and you just sit still and quiet. It sounds really boring, but the older you get, the more you realise… with events that have happened to me on a personal level and losing people, you know how quickly those moments can be taken away from you. It’s precious.

‘AI in music is fucking bollocks – it’s for robots, and we’re not robots’

It’s like you said earlier, about people being obsessed with looking at screens…

RH: You miss the moment or kill it. Maybe we’re looking at our phones trying to find that moment… I think real life struggles to compete with the moving images on a screen. The thing is with a phone or a computer, it’s all done for you – you don’t need an imagination. I find that concept absolutely terrifying – giving Artificial Intelligence the power to do everything for you.

What’s your view on AI in music?

RH: It’s fucking bollocks – there’s no debate. AI music is for robots – we’re not robots.

When we last spoke, in 2023, you’d just put out your compilation album, 28 Little Bangers From Richard Hawley’s Jukebox. How’s your jukebox going?

When we last spoke, in 2023, you’d just put out your compilation album, 28 Little Bangers From Richard Hawley’s Jukebox. How’s your jukebox going?

RH: It’s fucking great!

Have you put any new records in it?

RH: Not for a bit, because I’m happy with the selection… Actually, I put a lot of Led Zeppelin tunes on it and they sound fucking wicked. I’ve been a bit lazy… I’ve got The Harmonizing Four on there, and a few other tunes. You can only play 52 singles, so you’ve got 104 tracks.

My sons love at least half of what’s on there – they’ve got right into it because they wouldn’t have listened to that type of music at all. It’s the physical thing of pressing the buttons that they really like. We’ve got table football at our house, and they love – especially when I’m not there – getting their mates round with a few beers, playing the jukebox and table football. I’m really fucking glad that a 21-year-old and a 23-year-old find that a pleasing experience, instead of sat on a sofa with their mates, looking at their phones.

You’re bringing out People as a seven-inch single, with another new song, Bones, as the B-side, which isn’t on the album…

RH: That nearly made it, but there was something not quite right about it, not as a song, but being included on the album. Deep Space is a heavy track, but there’s a lightness to it – musically and with its lyrical content, it seems to fit into the vibe, but Bones is too heavy – emotionally and lyrically, and musically. It jarred a little bit, but it’s still a valid song. Me and the guys like it – we enjoyed playing it. It was also a question of the space on the record… I was tempted to cut another song and just have 11, but we went for 12 in the end because it seemed to be the right balance. There are three other tracks I haven’t released.

Are you looking forward to the tour?

RH: I can’t wait – we haven’t rehearsed yet. I don’t even know if it fucking works! Coming out of lockdown, we’ve enjoyed doing all the gigs that we’ve done – we were like sprinters in the starting blocks, waiting to get out. The joyfulness… not just for us, but for the audiences as well. To have that taken away for two years… It’s very simple – because we live in that scrolling culture and with Spotify and YouTube and all that, music’s become such an undervalued thing – it definitely is, because they don’t pay us!

If you consider people living in caves – our ancestors – where every waking second was about survival… They didn’t have a light switch, or a panel for the central heating, or Ocado or Tesco deliveries… All these things that we daily take for granted and clog up our brains too much.

Their existence could come to an end if they didn’t deal with [getting] firewood, clothing, heating, shelter, food… they had to create it or find it, but they still had time to paint on the walls. I’m not a betting man, but I would wager that there music involved as well… glottal stop singing or bits of wood being bashed on walls. There’s no documentation of it, but I’d put my last quid on it. What that tells you is that painting on the walls and, theoretically, music had as much value as finding a meal.

You’re playing a big show in Sheffield’s Don Valley Bowl this summer – Rock ‘n’ Roll Circus, with The Coral, The Divine Comedy and Gilbert O’Sullivan. That’s a super-group waiting to happen, isn’t it?

RH: Yeah – that’s your disparate thing… There are a lot of smaller artists playing too – I wanted it to involve a lot of younger Sheffield artists as well, which it does, in the other tent. I’m trying to give them a leg-up and flag attention to some labels that these are worthwhile acts and that they’ve got to check them out.

The selling point is that it’s Hawley’s biggest show, and this, that and the other… I try not to think about those kinds of things because it will fuck me up! It’s not an outdoor gig because it’s in a tent, but for something like that, you pray it doesn’t rain…

Heavy rain…

RH: Yeah, yeah, yeah – let’s not have that on the day…

‘Paul Weller has been so generous and so supportive of what I’ve done for years. We’ve tried to write songs together, but we’ve not quite managed to do it – we’ve got too much respect for each other’

You play on the new Paul Weller album, 66, don’t you? You’re on lap steel on a song called I Woke Up…

RH: Yeah – he’s a good pal. He just rang me up and said, ‘I’ve got this song on the new record…’

It’s a really nice song – folky, with some ‘60s pop strings on it…

RH: Yeah – it’s simple. It’s one of my favourites of the ballad stuff that Paul does. The funny thing is, and I said it at the time, is that tune will stick its little head up over his life and I think it will be one of his most remembered songs.

He’s been so generous and so supportive of what I’ve done for years – and been very vocal about it. The thing is with me and him is we’ve tried to write songs together but up to now, we’ve not quite managed to do it. Whenever we’ve tried… I think it’s because we’ve got too much respect for each other. That’s what Paul said [he does a Weller impression]: ‘It’s not working, Rich, because we’ve got too much fucking respect for each other…’ He’s enjoying doing what he’s doing, and that’s the main thing.

You’ve got a lot in common – you work with a regular band, you stick to your principles, but you’re not afraid to experiment…

RH: He’s not afraid to push it and he follows his own path – his own arrow – and that’s all you can do. You have to do what you do without willy measuring – don’t compare yourself to other people. You have to have the strength to do what you do, and don’t look over your shoulder at what some other fucker is doing. It’s not healthy.

You’ve done a fair few collaborations – would you like to do more?

RH: It’s whenever the phone rings… You can’t really choose those kinds of things. I’ve just been lucky that the phone’s rang with some really way-out things. It’s like when I met Duane [Eddy] – he said that he got into me because Nancy Sinatra had told him about me. When you actually sit back and think about it… it was Lee Hazlewood who told her about me. She said that her and Lee were driving around… I can’t remember where it was, L.A, Phoenix or wherever… listening to my stuff. That fucking blew my head off! How did that happen?

In This City They Call You Love is released on May 31 (BMG).

Please note: this interview took place on April 11, 2024 – sadly, Duane Eddy died on April 30 this year.

Richard Hawley will be touring Ireland and the UK from May 24:

May 24 3 Olympia Theatre, Dublin

May 25 3 Olympia Theatre, Dublin

June 2 Barrowland, Glasgow

June 3 Usher Hall, Edinburgh

June 5 De Montfort Hall, Leicester

June 6 Bristol Beacon

June 8 Eventim Apollo, London

June 9 Brighton Dome, Brighton

June 11 The Wulfrun Halls, Wolverhampton

June 12 02 Apollo, Manchester

June 13 The Glasshouse International Centre of Music, Gateshead

June 15 Olympia, Liverpool

June 16 Norwich Nick Raysn LCR UEA, Norwich

June 18 Guildhall, Portsmouth

June 20 Scarborough Spa, Scarborough

August 21 Beautiful Days Festival

August 29 Don Valley Bowl, headline show with special guests, Sheffield

August 29-31 End of The Road Festival