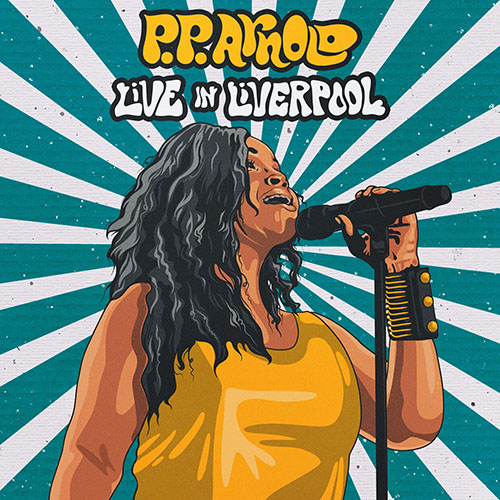

This month sees the release of a new live album by ’60s soul singer and mod icon, P.P. Arnold.

Live In Liverpool was recorded in 2019 at Grand Central Hall, on the tour for her album The New Adventures of… P.P. Arnold, which she made with Steve Cradock (Paul Weller and Ocean Colour Scene guitarist) at the helm.

It features versions of her hit singles, The First Cut Is The Deepest and Angel Of The Morning, as well as songs from 2017’s The Turning Tide and The New Adventures of… P.P. Arnold, which followed two years later.

Other tracks on Live In Liverpool include I Believe and Hold On To Your Dreams, which were both co-written with her son, musician Kojo Samuel, as well as Weller’s Shoot The Dove, covers of The Beatles’ Eleanor Rigby and The Beach Boys’ God Only Knows, and Magic Hour by Cradock.

Arnold, who turned 78 earlier this month, was born in L.A, and was one of Ike & Tina Turner’s singing and dancing troupe, The Ikettes, before she moved to Britain in 1966, where she launched a solo career that’s lasted almost 60 years.

She’s worked with acts including Mick Jagger, Rod Stewart, The Small Faces, Eric Clapton, Nick Drake, Barry Gibb, Peter Gabriel, Roger Waters, Primal Scream, Ocean Colour Scene and Paul Weller.

Early next year, her career will be celebrated with a new 3-CD box set, which will include rarities and unreleased material.

In an exclusive interview, Arnold talks to Say It With Garage Flowers about Live In Liverpool, collaborating with Cradock and Weller, her ‘lost years’ in the ’70s, the new box set, and appearing as the animated character, Cleo Nibbles – the Soul Mouse, on CBeebies show Yukee earlier this year.

“I just want to do as much as I can while I can,” she tells us.

Q&A

Before we start chatting about the new record, I just want to say that I’m not sure if I should call you P.P. or Cleo Nibbles – the Soul Mouse…

P.P. Arnold (Laughs): She’s a darling, isn’t she?

How did the opportunity to voice a cartoon character come about and was it fun to do?

P.P. Arnold: It was big fun! They contacted me, we did it and it’s really great. I love it, and I told them, ‘I’ll do a Cleo Nibbles album!’ I would love to do it for the kids.

Was that your first time doing voiceover work?

P.P. Arnold: I used to do loads of jingles and stuff, but it was the first time I’d done a voiceover like that. I like doing things that I’ve never done before.

Let’s talk about your new album, Live In Liverpool, which was recorded in October 2019 at Grand Central Hall, on the tour for your album The New Adventures of… P.P. Arnold. What was special about that show that made you decide to put it out as a live album?

P.P. Arnold: It was just a great gig, and it was in Liverpool, at a great venue… We recorded quite a few gigs, but that particular one was the last night of the tour, and it was just a great night… It was a solid show and it just worked.

How was it touring that album, which has a big production, with rich arrangements? You had an eight-piece band on the road with you…

P.P. Arnold: I was lucky because I had Steve Cradock batting for me – he dealt with the musical direction, and the musicians were all guys he knew – Andy Flynn [bass, guitar] was from the Steve Cradock Band. Tony Coote played drums on the album, so he knew what to do. I’d been touring with those guys previously, promoting The Turning Tide album, so we all knew each other. Steve and I have been working together for quite some time.

‘I always believe that Steve Marriott had something to do with bringing Steve Cradock and I together, spiritually’

You first met him in the ’90s, didn’t you?

P.P. Arnold: I remember it like it was yesterday. I was on the road doing theatre – the musical Once On This Island, which won an Olivier Award. Steve came to see me at the last show, which was in Birmingham – he showed up with flowers and introduced himself. They [Ocean Colour Scene] wanted me to go to the studio that night, but I was going back to London. So, after that, we hooked up when we did the tribute album for The Small Faces [Long Agos and Worlds Apart –1997].

What’s the chemistry that you have with Steve? Why does your relationship work?

P.P. Arnold: I always believe that Steve Marriott had something to do with bringing us together, spiritually – we both love Steve and he is in that mix… Steve [Cradock] and Sally [his wife] are like my babies – I sang at their wedding. It’s a family affair with us.

When I was working with Ocean Colour Scene, they were very young. Steve’s dad, Chris, didn’t quite get me – I was doing Reiki and stuff, because I was trying to put protection around everyone. He thought I was a bit of a witch or something… I was into nutrition and regeneration – my spirit is really strong – but I was going out on the road with these kids, and you know what they were doing back then… That had all been in my past… Anyway, it’s all cool now.

Let’s talk about some of the songs on Live In Liverpool. Baby Blue, which is on The New Adventures of… P.P. Arnold, was written by Steve Cradock and Steve Grizzell. Was it written for you?

P.P. Arnold: No – Steve [Cradock] brought it to the table. He had a relationship with Steve Grizzell. When he first presented me with the song, I didn’t think it was good for me – I thought it was too pop. I didn’t really get the lyric until I found out what the song was all about it – I like to know that… I like to know what I’m singing about, because, for me, it’s all about expression and telling the story.

When I spoke to Steve Grizzell, he told me that the song was about a young girl who had become pregnant and her parents made her give her baby away, so that was why she was ‘baby blue.’ Wow – then it hit me hard, because it was close to an experience I had had as a young girl, becoming pregnant. It was different, because she had to give her child away, but it was about the whole teen pregnancy thing and how it affects a young girl’s life.

She became a goth – the lyric says: ‘You should be standing out in peacock feathers like you used to do before you were baby blue.’ Once I got the story, I loved the song.

Musically, it has an authentic, late ’60s pop-soul feel…

P.P. Arnold: Exactly – Steve Cradock loves all that about me, that I’m authentic and from the ’60s, but still here and able to do that.

There’s a version of Everything’s Gonna Be Alright on the new live album. That song, which was originally released in 1967, has become a Northern Soul classic, hasn’t it?

P.P. Arnold: It was my first single and it did absolutely nothing. I missed that whole Northern Soul thing because I wasn’t here [in England] in the ’70s. I came back in the ’80s and that record was being sold for £100 and I thought, ‘Wow!’ That got me chasing my royalties…

I never used to sing it because I thought it was a bit twee at the time – I’d come from the States and being an Ikette… I wasn’t even sure about who P.P. Arnold was… Even though I was a soul singer, all my music was produced by English producers, so it wasn’t like Motown soul or Stax soul… I created that sort of pop-soul fusion…

You had that late ’60s London sound…

P.P. Arnold: Everything about me was British production… When I went back home to the States [in the ’70s] nobody was into what I was doing, but when I worked with Eric Clapton, he produced my roots and gospel sound and got more of a funky thing. But a lot of people didn’t get that because in the States it was what I called the ‘hot lick syndrome’ – everyone was trying to sound like Chaka Khan, and it was a modern gospel sound, so everyone thought what I was doing as a black American singer was lame.

A lot of people still don’t get my sound because it’s more old-school gospel and soul-based. My thing is about singing songs – it’s not about ‘licking’ all over the place.

I can do that, but I have more of a melodic sound in the way in which I express a song. I’ve got my own lane – this is me, I’m P.P. Arnold and I have a distinctive sound.

‘A lot of people still don’t get my sound because it’s more old-school gospel and soul-based’

There’s a great and very powerful version of (If You Think You’re) Groovy on the live album. That song was written for you by Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane from The Small Faces…

P.P. Arnold: Absolutely – they first wrote Afterglow for me, but they kept it back and gave me (If You Think You’re) Groovy… I’ve done some versions of Afterglow but I haven’t released any of them because of all the politics with the publishing and his family not getting the rights. I know Steve would be pissed off about what’s happened with that. I’ve stayed out of it, but recently Steve [Cradock] and I did a really beautiful acoustic version of I’m Only Dreaming [Small Faces song] that’s going on the box set I’ve got coming out. I didn’t want to put it on there, but it’s such a lovely version.

When’s the box set being released?

P.P. Arnold: February. There should be pre-orders around Christmas time. It will have unreleased and rare stuff on it, including the tracks I did with Chaz Jankel, which were never released. The stuff I did with Dr. Robert is on there…

I love the 2007 album you made with him: Five in the Afternoon…

P.P. Arnold: It’s a great record, but the label it was on shut down and it never got the exposure.

Let’s go back to the live album…You co-wrote I Believe, which is on it, with your son, Kojo…

P.P. Arnold: Yeah, And Hold On To Your Dreams, which was the first single. When I did Burn It Up with The Beatmasters, I was the only live thing on the record, but I was the only one who couldn’t get a record deal… I was being really revolutionary about it, and after that I recorded a track called Dynamite – that’s going to be on the box set. I did it with Kenny Moore, who was Tina Turner’s keyboard player, and The Beatmasters produced it.

I needed to get my shit together, so I had a 16-track setup at my house that Kojo was cutting his production teeth on – he produced his momma. So, we did those tracks [I Believe and Hold On To Your Dreams] and I was trying to get a deal with them – and we did them in a real dance format, but we couldn’t get a record deal.

I didn’t want him, as a young man, to have to be going through my struggle and disappointments – the ageism thing was being laid on me – because he was doing some great work… Steve [Cradock] heard those tracks, and we decided to do them, and they’re great.

I Believe has a ’70s disco feel, and is very spiritual – it’s a positive song…

P.P. Arnold – Both of those songs are very spiritual. You said I Believe has a ’70s thing on it – that’s cool, because I was feeling Stevie Wonder – that kind of groove. Kojo and I wrote those songs together – he laid the tracks down, and I had the lyrics… He’s great – I’d love to be working with him now, but he don’t have time for me!

Medicated Goo, from The Turning Tide, is on the live album – it’s a great version. That’s a big song when you play it in concert…

P.P. Arnold: It is, and I make sure that everyone knows that the ‘medicated goo’ is a healer… It’s not just about getting high…

I really like your version of the beautiful Sandy Denny song, I’m A Dreamer, which you recorded for The New Adventures Of… P.P. Arnold, and is also on the live album. She was such a great singer and songwriter. Did you ever meet her?

P.P. Arnold: I didn’t get to meet her, because during the ’70s, I’d gone back to America, and I’m still coming back from that period…

You call that time in the ’70s ‘the lost years…’

P.P. Arnold: Yeah – the lost years… Had my stuff from then been released at the time – the Barry Gibb tracks, The Turning Tide and the Eric Clapton productions – it would’ve been a whole other story…

Talking about Sandy Denny, who was part of the ’60s and ’70s English folk scene, you and Doris Troy sang backing vocals on Nick Drake’s Poor Boy, from his 1971 album, Bryter Layter. Do you have any memories of that session?

P.P. Arnold: Yeah, I remember Doris Troy calling me and saying, ‘Hey, baby, what you doing tonight? Do you want to come and do a session with me?

We went to Fulham [Sound Techniques studio, Chelsea] with the producer, Joe Boyd… It was another session, y’know… but there was a vibe that night with him [Nick Drake] – he was very reserved and quiet… a very shy guy.

We worked with him quite closely, and he explained what he wanted us to do, and what the song was about. We just gave him what he wanted. As I talk about it, I’m getting chills… It was a lovely evening, working with a really nice guy.

At the time, I didn’t really know who he was, and I didn’t find out about that track until I came back in the ’80s.

Paul Weller is a big Nick Drake fan, and you’ve worked with Paul…You sing his song Shoot The Dove on Live In Liverpool… How’s Paul to work with?

P.P. Arnold: I love Paul – he has been so supportive. When Steve Cradock and I were doing The New Adventures… I told him about the tracks [from The Turning Tide] that I’d finally got the licence for and that I needed somewhere to mix them. Paul and Steve let me mix them at Black Barn. I met him in the ’90s, when I was doing stuff with Ocean Colour Scene, and I went to a couple of his shows. He’s lovely, and he gave me Shoot The Dove and When I Was Part of Your Picture.

There’s a lovely moment on the live album where you sing Eleanor Rigby, in Liverpool, and you tell the crowd it’s one of your favourite songs by The Beatles. I really like your version of it, with the church-like organ on it…

P.P. Arnold: Yeah – that whole Hammond vibe…

You recorded Eleanor Rigby on your second album, Kafunta, which came out in 1968. Did you meet The Beatles?

P.P. Arnold: I’ve met Paul a couple of times – we once met in Harrods, doing Christmas shopping – but I didn’t know John or Ringo. I met George, because we did the Delaney & Bonnie tour together. We had to go over the Channel in a boat – I shared a cabin with Lesley Duncan, George and Billy Preston. Billy was a gentleman – such a beautiful guy. I knew he was gay, so he wouldn’t be jumping on my bones!

I knew him from church – when I was 12 years old, me and my sister were in a gospel group that sang at Billy’s church. He also used to hang out with Ike and Tina Turner.

On Kafunta, you recorded songs by The Beatles, The Beach Boys and The Rolling Stones. Was that your decision, or was it down to your producer, Andrew Loog Oldham?

P.P. Arnold: Andrew had a vision and great ideas, but I was never forced to sing anything. If I didn’t like a song, I didn’t have to sing it. I didn’t have confidence in myself as an artist. I never came into the industry saying, ‘I’m an artist and I want to do this, or I want to do that…’ That’s why I got lost in the ’70s, because the universe had always put me with people who knew what they were doing.

‘I just want to do as much as I can while I can, and if it’s possible to move onwards and upwards, instead of going round in circles, that’s what I want to be doing’

There’s a nice live version of Life Is But Nothing, which was on your first album, The First Lady of Immediate, on the new record. You’d never sung that live before, had you?

P.P. Arnold: I’d never sung it… Steve Cradock insisted I sing it, and now I sing it all the time.

The live album ends with The First Cut Is The Deepest, which was the song that kick-started your career. You had a hit with it in 1967. It was written by Cat Stevens and you recently sang it on stage with him…

P.P. Arnold: I did – in Henley. That was great. It was the first time I’d seen him since 2007, which was the first time I’d seen him since 1968! The concert was for Mike Hurst, who produced The First Cut Is The Deepest, as he has Parkinson’s – it was a fundraiser for charity.

‘I’m making another record – I’m doing a duet with Paul Weller and I think I’m going to do some more stuff with Steve Cradock’

After Everything Is Gonna Be Alright didn’t happen, I really needed a hit if I was going to stay here. My kids were with my mum [in the US], and she gave me six months to make it work, but Mike brought that great song to the table, and it’s the story of my life. It was as if the song had been written for me.

Any plans for a new studio album?

P.P. Arnold: Oh, I’m making another record. I’ve finished a track called I Know We’ll Get There, and I’m doing a duet with Paul Weller. I heard from him yesterday, when he was in the States… It’s just about [having the] time – when can we do it? Paul’s got a lot going on, and I haven’t got a label behind me, driving things… Anyway, he’s cool and we’re staying in touch about it – divine order will make it happen.

Steve Marriott will make it happen…

P.P. Arnold: Yeah – he’ll make it happen, and I think I’m going to do some more stuff with Steve Cradock that will go on the album.

You’ve had to deal with tragedies, difficulties and a lot of bad luck in your life, but you’re always such a positive person. I’ve met and interviewed you a few times and I find you inspirational – you always cheer me up and you have an aura…

‘I just want to do as much as I can while I can, and if it’s possible to move onwards and upwards, instead of going round in circles, that’s what I want to be doing’

P.P. Arnold: Thank you. I’m pure energy. There’s no way I could do it without it. I can’t mess around with my vocals, so I’ve never really been into drinking a whole lot, as it dehydrates me and affects my voice. I love to sing. There’s other stuff you do when you’re young and you’re growing up… I couldn’t be doing what I’m doing and looking like I’m looking if I was doing that stuff…

You look great…

P.P. Arnold: Well, thank you. I’ve invested in my health and fitness. Hey, man, how long that’s going to be going on, I don’t know… What I do know is that I just want to do as much as I can while I can, and if it’s possible to move onwards and upwards, instead of going round in circles, that’s what I want to be doing. I want people to know that I’m still out here, fighting the good fight.

Live In Liverpool is released on October 18 (Ear Music).

A new 56-track, 3-CD P.P. Arnold box set will be released by the Demon Music Group early next year.

For P.P. Arnold UK tour dates this autumn/winter, visit https://pparnold.com/tours-gigs.