It’s been 10 years since the last album by The Dreaming Spires – 2015’s Searching For The Supertruth.

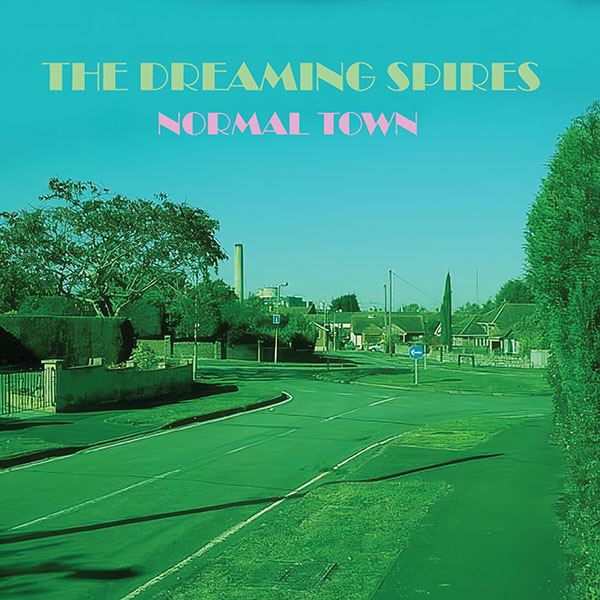

Now, the Oxford-based Americana and power-pop band – founding members and brothers Robin and Joe Bennett, plus Jamie Dawson (drums), Tom Collison (keys) and Nick Fowler (guitar) – are back with a brand-new record, Normal Town.

Their third album, it explores themes of home, nostalgia, alienation, escapism and the beauty – and drudgery – of the everyday.

The sublime, nostalgic and atmospheric title track, which was also the first single, pays homage to their hometown of Didcot, which, in 2017, was deemed “the most normal town in England” by a bunch of number-crunching researchers.

“I don’t want to die in a normal town,” pleads Robin Bennett, over plaintive piano and cinematic twangy guitar.

‘Normal Town is less jangly than their previous albums – no 12-string Rickenbackers were used during the making of this record’

Didcot is also referenced in Cooling Towers – a reflective, bass-driven, country-tinged song inspired by the town’s power station, which was a famous landmark, until it was finally demolished in 2020.

Less jangly than their previous albums – no 12-string Rickenbackers were used during the making of this record – Normal Town has anthemic and political, Who-like power-rock (Normalisation), which sounds like Big Star covering Baba O’Riley; the Springsteen-esque crime story Stolen Car; 21st Century Light Industrial – imagine the observational songwriting of Fountains of Wayne but transplanted from New York to a business park in Oxfordshire – the folky travelling song, Coming Home, and the spacey psychedelia of Where I’m Calling From, which is a message beamed in from the future.

In an exclusive interview, Robin Bennett talks us through the concept behind the album and shares the inspirations for some of the songs.

“It’s quite a nostalgic album – a lot of the time period I’m talking about is as much about 25 years ago as it is about now,” he says. “You can get to adulthood and be a bit disappointed by it – where’s the transcendent experience we were looking for?”

So, is this his mid-life crisis album? “You can be the judge of that…”

Q&A

Let’s talk about the first single, Normal Town, the song from which the album takes its title – it’s about the ambivalence many people feel towards their hometown. In your case, it’s Didcot in Oxfordshire, which, in 2017, was found to be the most normal town in England, according to a study by researchers. The song was inspired by those findings…

Robin Bennett: The research was based on metrics and questionnaires with residents in various places around the country, and Didcot was the closest match to the average. We’ve all grown up around Didcot – it’s our local town. Jamie was born in Didcot – his parents still live there – and Joe and I grew up in Steventon, which is a couple of miles from Didcot.

How did you feel when you heard about the results of the study?

Robin Bennett: I found it amusing, and I think that was when I first started writing the song or got the idea for it. There was a backlash in Didcot, as you might expect, and there was an artist that went round putting different places on street signs, like turnings to Narnia and Middle Earth.

The song deals with the idea of escaping from where you grew up, rather than being stuck there all your life – it feels like your take on Born To Run, but less bombastic…

Robin Bennett: Yeah – there’s definitely a bit of that.

It also mentions drunken violence on a Saturday night… I grew up on the Isle of Wight, so I can relate to that small town mentality…

Robin Bennett: I’ve never been to the Isle of Wight…

Really? I’m surprised you haven’t played there.

Robin Bennett: I’d like to.

‘I did a painting of the Didcot Power Station cooling towers when I was about 12 – I’ve always been fascinated by them’

There are small towns everywhere, so it’s a song that most people can relate to…

Robin Bennett: Yeah – I think the point is that it could be any town in Britain.

Didcot is best known for its power station, which you reference in the song Cooling Towers. The power station was turned off in 2013, but in 2016 four men who were working on-site died when part of the building collapsed – you mention that in the lyric…

Robin Bennett: That’s right – it had to be demolished bit by bit, because it was such a big project. So, they did a couple of the cooling towers, and then another couple, and then they had to do the turbine hall. I can remember that when I was at primary school, we got taken on a tour of the turbine hall.

I used to play for an under-13s cricket team and our pitch was right next to the cooling towers. Everyone in the area would know they were getting close to home when they come back from a holiday or something, because they could see the cooling towers – it was the local reference point. I did a painting of the cooling towers when I was about 12 – I’ve always been fascinated by them.

Cooling Towers is a song about going back to your hometown after spending some time away…

Robin Bennett: I think a lot of the album is about the back and forth between going away to adventurous places, maybe with music, and then coming back to a kind of normal place.

So, would you describe Normal Town as a concept album?

Robin Bennett: I think it has a bit of The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society about it, where not every song on it fits the concept, but it sort of feels like a concept album. When I was finishing it off, I had four or five core songs, and then towards the end, I deliberately wrote a couple to round off the concept.

‘A lot of the album is about the back and forth between going away to adventurous places, maybe with music, and then coming back to a kind of normal place’

There are recurring themes – your hometown, childhood, alienation, travelling, the drudgery – and beauty of – everyday life… So, was the song Normal Town the springboard for the rest of the album?

Robin Bennett: It was definitely one of them, and Cooling Towers also helped to set up the concept. There was also Normalisation, which contains the word ‘normal’ but is about something slightly different.

Let’s talk about Normalisation, which is one of the bigger and more anthemic songs on the record – it’s got a power rock feel and it reminds me of The Who’s Baba O’Riley. It’s a very topical and political song and you uploaded a lyric video of it to YouTube in the wake of some of the stuff that’s been happening in the UK with the rise of the far right. You used an image that you took of a protest outside of a hotel that was being used to house asylum seekers… So, is Normalisation a relatively new song?

Robin Bennett: No – that’s the funny thing about it. It was from about 2020, when I was first recording some demos. I kept thinking, ‘this song won’t be relevant if I don’t put it out tomorrow,’ but it keeps gaining relevance.

So, was it written around the time of Brexit?

Robin Bennett: Not around the vote, but maybe around some of the stuff that was happening when the language around it was escalating and when people like Nigel Farage were being turned into mainstream figures by the press and the media, rather than being on the fringes.

The song feels like a call to arms – a plea for something to change. It’s quite positive…

Robin Bennett: It’s unusually positive! It’s easy to drift into apathy, and I often do, but when something as serious as this comes up, and you know that people in your local community are vulnerable, you’ve got to find a bit of bravery. So, maybe the song is trying to inspire a bit of that.

The lyric also mentions people losing their jobs – it alludes to how some employees, like those in the Mini factory in Oxfordshire, are being made redundant, as manufacturing jobs are being replaced by robots…

Robin Bennett: The song draws together what’s going on with right-wing figures and billionaires, like Musk – there’s a direct link, as Musk spoke at the [Unite The Kingdom] rally.

And there’s also the fear of AI…

Robin Bennett: Yeah – what was happening when I wrote it is now becoming more prevalent with AI, so I think it says what it needs to say pretty well.

The song 21st Century Light Industrial is also about something most of us can relate to – being stuck in a dead-end job, day in, day out… It’s about wanting to escape from the nine-to-five…

Robin Bennett: As I said earlier, Joe and I grew up in Steventon – which is about three or four miles away from Didcot. In-between, there’s Milton Park, which, in my childhood, had just a couple of distribution centres for lorries, but in the Blair era it became a big industrial park. Nowadays it’s quite slick, and it’s got loads of tech businesses – it’s a lot more modern – but when I used to work there it was mostly dilapidated warehouses.

You’d always have the commercial radio station on, and it would just play the same songs repeatedly. When I was starting out in music, it was quite motivational for me to get out of there.

Stolen Car is a song about someone who has fallen in with the wrong kind of people…

Robin Bennett: It’s a slightly exaggerated version of a story that a friend of mine told me – he got chased by the police, but in his own car, rather than a stolen one. He loves music and I also wanted to sort of express what music can mean to people, even when things aren’t working out.

I like the lines: “I’ve got a worn-out soul, but I’m still on my feet. Give me that rock ‘n’ roll. I want to feel my heart beat…’

Robin Bennett: It’s like a slightly less jubilant version of Dusty In Memphis [from The Dreaming Spires’ 2015 album, Searching For The Supertruth], where you’re hanging on in there…

Linescapes is another song about trying to turn things around and escape from the everyday….

Robin Bennett: Yeah – that came from a friend of mine called Hugh Warwick, who is an ecologist – he wrote a book called Linescapes. He came round my house, and he told me about the book – he said he couldn’t think of what to call it. So, I came up with the title for it and I then I thought I’d write a song called Linescapes. The book is about the different industrial lines that we create across landscapes – some of which can be very harmful and some of can be quite beneficial for wildlife or ecology.

Our house in Steventon was right next to the railway – there used to be a big station there, and then it got moved to Didcot. I was born next to Paddington station, so I’ve always had this sort of appreciation of the railway. When I was 12, I remember walking along the railway from our house to Didcot, which was obviously illegal…

A lot of the songs on the album deal with escapism…

Robin Bennett: It’s quite a nostalgic album – a lot of the time period I’m talking about is as much about 25 years ago as it is about now. You can get to adulthood and be a bit disappointed by it – where’s the transcendent experience we were looking for?

So, is it a mid-life crisis album?

Robin Bennett: You can be the judge of that…

Coming Home is more stripped-back, with a slightly folky feel and some nice harmonies – it’s got a touch of Crosby, Stills & Nash. It’s about not being able to stay in one place for too long. In the lyric, you sing about feeling like a rolling stone. It deals with how as a touring musician means you can escape from a normal existence…

Robin Bennett: Yeah – and how the more you do it, you partly miss some of the changes that are happening back home because you’re away half the time. You can have a crisis: where do you belong? You belong in a state of travel… and then there are the places back home… There’s an old shopping street in Didcot called Broadway – you think Broadway is associated with glamour and New York… It’s a funny street – it’s only got shops on one side…

‘It’s quite a nostalgic album – a lot of the time period I’m talking about is as much about 25 years ago as it is about now. You can get to adulthood and be a bit disappointed by it – where’s the transcendent experience we were looking for?’

With Coming Home, I was also thinking of Jamie, our drummer – he moved to LA twice, and then both times he moved back to Didcot. I thought that was funny – in some ways, home is where the heart is, isn’t it, ultimately…

Where I’m Calling From stands out for me, as it’s very atmospheric, with a psychedelic and spacey feel… It feels like it’s a message being beamed in from the future…

Robin Bennett: I’m happy to hear that. In the sequencing, it ended up near the end, when things are getting a bit more psychedelic.

The first half of the album is quite upbeat, but the second half has more ballads and feels more restrained…

Robin Bennett: That’s probably fair… When I started assembling it, we weren’t playing live much – it was the pandemic, for one thing, and then we took a while to get going after that. So, it wasn’t formulated in the rehearsal room… I think there’s enough songs on it that fit The Dreaming Spires mould, but you’ve got to keep things fresh, haven’t you?

It’s less jangly than your other albums…

Robin Bennett: It doesn’t have any 12-string Rickenbacker on it – it’s the first one that doesn’t… It does have some 12-string acoustic on it.

What influenced the record musically? How did you want it to sound? It’s quite layered, with piano and synth…

Robin Bennett: I played all the piano on it – that’s how I wrote the songs, so maybe that’s why there are more ballads… Tom [keys player] added some more ‘out there’ sounds… I wanted to give the record a Daniel Lanois atmosphere [Bob Dylan, Neil Young, U2]. Even the songs that have classic rock stylings have also got uncomfortable sounds on them that make them seem a bit off, like Wilco sometimes use – that was intentional.

Where did you make the record?

Robin Bennett: I recorded the songs to a drum machine in my front room, and then we added the band’s rhythm section at Joe’s studio. Tom did his bits remotely, and Nick, who plays guitar, also went to the studio, where we mixed the album. I sketched the ideas out and then added the others – it’s not ideal, but it’s produced something slightly different.

‘I wanted to give the record a Daniel Lanois atmosphere. Even the songs that have classic rock stylings have also got uncomfortable sounds on them that make them seem a bit off’

The last song, Real Life, is about making the most of what you’ve got – taking each day as it comes and not wishing your life away…

Robin Bennett: It’s the most rootsy-sounding track on the album and I like the freshness of it at the end. The album is about the contrast between home – and reality – and the fantasy of escape. So, maybe it’s about coming to terms with everyday life, which is your reality, and that’s okay.

So, are you pleased with the album?

Robin Bennett: I am – it’s given us the momentum to get going as a band again, which is nice.

On that note, it’s been 10 years since your last album, Searching For The Supertruth. How does that feel?

On that note, it’s been 10 years since your last album, Searching For The Supertruth. How does that feel?

Robin Bennett: When you haven’t got a huge marketing budget, sometimes music takes time to sink in with its audience – I think that one found its audience over time. So, when we first toured it, it was good, but some people have got really into the songs over time. Playing them now, it’s really nice to see the response they get – songs like Dusty In Memphis and We Used To Have Parties. People really seem to have connected with them.

During the past 10 years, you’ve also been part of the Bennett Wilson Poole supergroup project, with Danny Wilson (Danny and the Champions of the World) and Tony Poole (Starry Eyed and Laughing) – you made two albums together…

Robin Bennett: Yeah – I’m really proud of both of those records.

Tony Poole has mastered Normal Town…

Robin Bennett: It was nice to be able to work with Tony – he’s a great mastering engineer, as well as everything else.

The other thing I should mention is that for the past seven years I’ve been a local councillor. For a time, I had a cabinet role where I was responsible for the regeneration of Didcot, which is kind of ironic. I felt like I couldn’t hold back on releasing this album because I was actually working on some of the stuff that I was talking about on the album in my job.

What do you think the people of Didcot will make of the album?

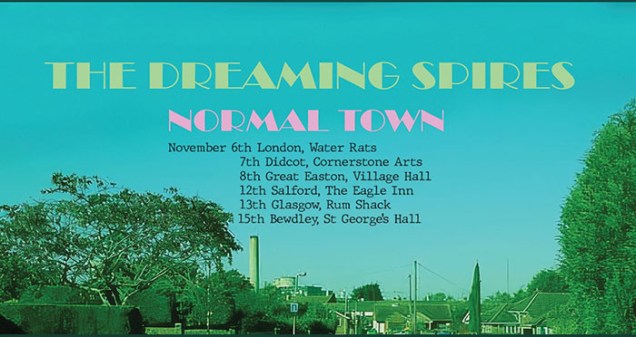

Robin Bennett: I hope they’ll appreciate that it comes from a place of love. We’re doing a small tour and we’re actually playing in Didcot, at the Cornerstone Arts Centre, which is owned by the council. I’m really proud that there’s an arts centre there and that culture is happening in Didcot – it’s not just in cities…

‘Some of the atomisation we’re seeing in society is because of a lack of places for people to hang out together in a social way’

When towns are being planned, people give thought to where they are going to live and where they’re going to work, but, for a time, they put all the workplaces on an industrial park, and they forgot where culture was going to exist. I think the album has something in it about creating some meaning in our lives… You need places like arts centres and venues to give people the space to create. It’s really important for the community. Some of the atomisation we’re seeing in society is because of a lack of places for people to hang out together in a social way.

It’s a shame that Didcot Power Station has been demolished – you could’ve launched the album there with a giant inflatable flying over it, like Pink Floyd did at Battersea Power Station, with the pig on the cover of Animals…

Robin Bennett: (laughs). That would’ve been very psychedelic…

Normal Town is released on November 7 (Clubhouse Records).

The Dreaming Spires are on a UK tour in November: