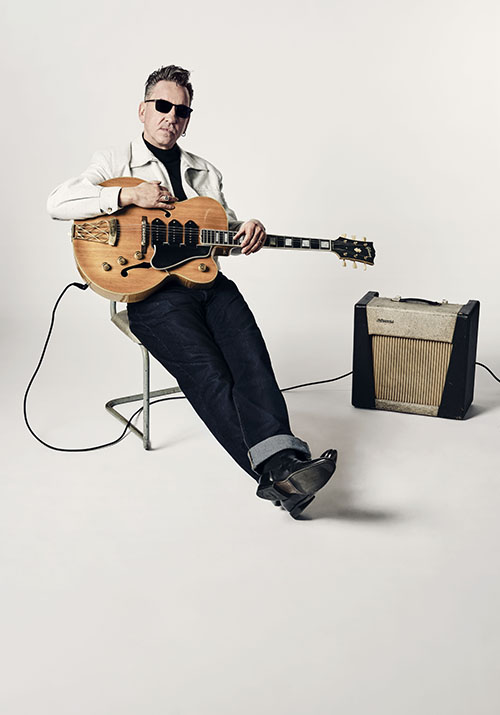

In 2023, Sheffield singer-songwriter and musician, Richard Hawley, teamed up with label Ace Records to release a brilliant and eclectic compilation album of garage rock, surf, psych, rock ‘n’ roll and R & B seven-inch singles from the ‘50s and ‘60s that he’d hand-picked from his own vinyl collection.

Called 28 Little Bangers From Richard Hawley’s Jukebox, it was full of killer riffs, dirty sounds, fuzzed-up guitars, mean organ and twangy licks.

This year, he’s lifted the lid on the jukebox once more, replaced the singles with a bunch of new ones, and unleashed the second in his compilation series, Little Bangers From Richard Hawley’s Jukebox, Volume 2, which is released on January 30, via Ace.

Arguably better than the first album, it’s dedicated to his friend and musical collaborator, guitar legend, Duane Eddy, who died in 2024 – Eddy’s raw, bluesy and groovy 1965 track, Trash, is on the compilation.

Well-known artists like Elvis Presley, Gene Vincent, Dick Dale and Chet Atkins sit alongside obscure 1970s Welsh psychedelic band, Sunshine Theatre, whose song Mountain is the rarest track included – only 50 copies are said to have been made –and ’60s Orange County garage-rock band, The Last Word, who only put out one single, the Them-like, Sleepy Hollow. Hawley bought the seven-inch by The Last Word for $50, but he says it’s now worth closer to $1,000!

To discuss his rare record finds, and talk about some of the highlights of the new compilation, Say It With Garage Flowers got Hawley on the phone in mid-December last year, shortly after he’d played three sell-out shows at Sheffield’s City Hall.

“Call me a sad fucker, but some of the happiest moments in my life have been when you find that record you’ve been wanting to find for so long,” he tells us.

Q&A

Your first compilation, 28 Little Bangers From Richard Hawley’s Jukebox, came out in 2023. When we last spoke, you said that you’d already put together enough songs to do six volumes, but that you wanted to do 10 in total. Is that still the intention?

Richard Hawley: I think so – I’ve got enough to double that, but it’s whether people will be interested in that many… It’s a bit of an indulgence, but as long as I can take people who are interested in what I do into musical areas that they maybe wouldn’t have thought of listening to, then it’s relevant. So, yeah – I’ll just keep going until folks have had enough.

I think the new compilation is better than the first one – how did you approach it?

It was a similar thing, but the difference between this one and the first was that with the first one, Graham [Wrench – manager] nagged me, because I’d been dragging my heels quite a bit, and Liz [Buckley – head of A & R at Ace Records] said, ‘Rich – we need the list…’ So, in all honesty, I just grabbed a bunch of singles, and pretty much all of those made the grade.

I don’t DJ much these days, but when I do, I have these boxes that have amazing records in them, so, when I lift out a handful of them, it’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that it’s going to be a bunch of interesting records…

I started taking notes and writing down things that I heard or had played. I’ve got this pretty massive cabinet that’s screwed to the wall that has most of the seven-inch singles in it, although some have spilled out of there now because there’s so many. I don’t have them in alphabetical order, because I’ve noticed that whenever I’ve done that, I tend not to play anything… It’s an odd thing… I’m a bit of a lazy c*** with things like that, so I just have them in there randomly, and I’ll reach in, pull something out and play it. I like that because I don’t really know what it’s going to be. A lot of record collectors will probably be horrified by that! (laughs).

I like the randomness of it. I think there’s a certain aspect of record collecting where you’re on some form of the spectrum. I’ll hear something, buy it, forget about it and then rediscover it, which is a nice thing for me. And also, I’ve got the memory of a flea: ‘Ooh – this is new…’, while my wife’s there, rolling her eyes…

‘I don’t know what the wattage of my jukebox is, but it’s bloody loud! And for technology that’s 70 years old… It’s from 1955. It’s incredibly punchy and the bass on it is amazing’

How often do you change the singles you’ve got in your jukebox?

If I’m busy, when I’m writing, or I’ve got my mind on other things, I’ll forget about it, but when I do change it, it’s quite radical.

I can become obsessed with it… It’s also wanting to hear it, because it’s such an amazing thing – I don’t know what the wattage of the jukebox is, but it’s bloody loud! And for technology that’s 70 years old… It’s from 1955. It’s incredibly punchy and the bass on it is amazing.

I read about how when they used to put out seven-inch singles, they used to roll the bass off them because the bandwidth of radio waves in the ‘50s couldn’t handle loads of bottom end. We’ve got digital now, which can take a wide band of frequencies. So, in the ‘50s, they’d roll the bass off on the equipment, so they could play the singles on the radio – and that happened right up until the early ‘70s, apparently.

Where’d you’d hear the bass was on jukeboxes – they would have the speaker capability to put the bass back into the singles, and that was why they were so exciting. And you’d also hear records at fairs, like on the waltzers, and they’d always sound that little bit more exciting. When you’re on a waltzer, it’s a near-death experience anyway, and you’re being swung round by these dangerous-looking lads…

I like the sleeve notes you’ve written for the new compilation – in the introduction, you say that you were lucky to have grown up in a house when there was music playing all the time. When you were young, your mum would listen to the radio while she was cooking, or sometimes she’d put a record on, and your dad would be playing his guitars. When you went to other people’s houses, there wasn’t music playing…

Yeah. Folks wouldn’t even have a TV or a radio on – not even in the background. There was complete silence, and it was really weird.

I used to find it quite strange that a lot of my friends’ parents weren’t remotely interested in engaging with books, radio, TV, music, or a magazine – there was nothing, and they just sort of sat there… Although, to be honest, as I’ve got older, I crave silence and peace. I think it’s definitely an age thing.

Because of what do, I’m always in a loud environment – even if it’s just the thoughts in my head, there’s a lot going off all the time. I have large swathes of time where I like to just shut it all out. It’s not just an age thing – I think it’s the era that we live in, with the internet and stuff like that.

I rarely watch TV and I go on the internet to look for records, clothes and guitars – three interests that I’ve had since I was about five.

‘My record playing is usually accompanied by alcohol. When you’re having a couple of Guinnesses, you just want to listen to some music – they go hand in hand’

The whole noise of social media… I made a decision a long time ago that it wasn’t for me. You can get drawn in, because it’s a seductive world, to talk and engage with people, but I’d end up getting involved in some kind of nonsense…

I love silence. My record playing is usually accompanied by alcohol. When you’re having a couple of Guinnesses, you just want to listen to some music – they go hand in hand.

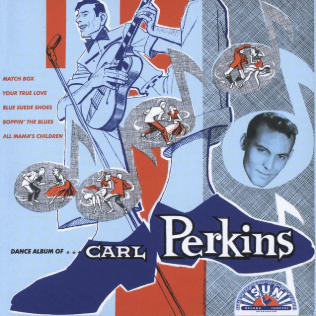

In the sleeve notes, you mention how your dad had to sell a lot of his rare records when the steel workers’ strike took place in 1980, but, subsequently, you’ve spent a lot of time trying to track them down. There’s a great story of how you found a copy of one of the albums he’d been forced to sell – Dance Album of Carl Perkins – in a record shop in Wakefield, and it was your dad’s actual copy! It had his name and address on it, written in his handwriting, on a sticker that was on the back cover…

Yeah – not only did I find the actual copy that he sold, but it made me think, ‘where the fuck had it been all those years?’

Finding that Carl Perkins record was a Holy Grail moment, because, not only had I got a copy of it, but it was the copy… Funnily enough, it was virtually unplayable – the surface noise on the record was way louder than the music… But my uncles, Kenny and Eric – I call them uncles, but they were friends of my dad’s – bought me a mint copy of Dance Album of Carl Perkins for my fiftieth. They’re lovely blokes. Kenny used to run Kenny’s Records on The Wicker [in Sheffield], which we used to go to a lot.

Finding that Carl Perkins record was a Holy Grail moment, because, not only had I got a copy of it, but it was the copy… Funnily enough, it was virtually unplayable – the surface noise on the record was way louder than the music… But my uncles, Kenny and Eric – I call them uncles, but they were friends of my dad’s – bought me a mint copy of Dance Album of Carl Perkins for my fiftieth. They’re lovely blokes. Kenny used to run Kenny’s Records on The Wicker [in Sheffield], which we used to go to a lot.

You’ve dedicated the new compilation to your friend, Duane Eddy, who died in 2024, and you’ve included a track of his called Trash on the album. It’s originally from his 1965 album, Duane A Go Go Go. It’s great – a bit bluesy and groovy, with some raw, wailing harmonica on it…

Yeah – it’s a motoring track. You can imagine getting in a car to it and probably driving faster than you should. That album with Trash on it is one of the last great records that he made – and he also did Duane Does Dylan [in 1965]. I had such a wonderful experience working with Duane – he and I became really close. I miss him and I just wanted to dedicate the record to him in his honour.

The compilation opens with The Last Race by Jack Nitzsche, which some people will know from the soundtrack of Tarantino’s film, Death Proof. It’s a good way to start the album – very menacing, with a revving engine, big strings, toms and a twangy guitar…

I’ve made quite a few records in my time, so I’m aware that the first track has to get people’s attention. There was a fashion at the time for starting records with the sound of a motorbike – I’ve just found another one, which is great and is going on the next compilation. It’s Scramble by The Royal Rockers – have a listen to that. You’ll like it. There’s quite a lot of records that I have that were obviously appealing to a certain part of the population – bikers.

The last song on the compilation, Cycle-delic by The Arrows, featuring Davie Allen, is another biker track…

It’s insane… That was when all the bikers got into acid – it was really heavy and dark shit. There was that culture and it culminated with Altamont and the horror at a Rolling Stones concert [in 1969]. It was grim. Cycle-delic had to go last because I’m curious about how many people will make it to the end of the compilation! It’s like the sonic equivalent of having root canal treatment, but the dentist has no anaesthetic! It’s pretty fucking hard to listen to.

There’s a great Jet Harris track called Man From Nowhere on the compilation – I hadn’t heard it before. It has spy-film guitar and big strings…

I don’t know why it was never a single. There’s an accompanying video to it – look it up on YouTube. It’s amazing!

Haven’t you had the track made up and pressed as a single?

Yeah – there’s a mate of mine who knows various nefarious sources… It means I can play it on the jukebox.

The compilation is front-loaded with instrumentals but the first vocal track we get to hear is Put The Blame On Me by Elvis Presley with the Jordanaires. I didn’t know the song, but it’s great – it’s from 1961 and in the sleeve notes you describe it as ‘a sort of prototype of garage rock…’

Yeah – it’s the chord structure and it’s almost got a strip club / go-go beat – you can imagine some poor girl having to take her clothes off to it, to earn her living. Chordally, it’s very similar to (I’m Not Your) Stepping Stone by The Monkees. There was a load of garage records like that… No Friend of Mine by The Sparkles is another one. All those garage bands would’ve used that chord structure at some point: The Seeds, The 13th Floor Elevators, The Chocolate Watch Band…

You’ve included a version of (I’m Not Your) Stepping Stone by British band The Flies on the compilation…

It’s a lot dirtier than The Monkees’ one – I’ll stick my neck out and say that’s it’s the best version of Stepping Stone. I’m always amazed that The Monkees were allowed to do something like that, because it’s pretty aggressive.

Another garage-rock track on the album is Baby I Go For You by The Blue Rondos, which was produced by Joe Meek…

It’s testament to what he achieved with sort of limited equipment, and it’s quite obvious that a lot of his ideas were pilfered by other producers at the time, because he was light years ahead of everything else that was going on.

The rarest record on the compilation is Mountain by the Welsh band, Sunshine Theatre – when it came out, in 1971, there were only 50 copies of it ever made…

Apparently – and I don’t know whether they exist… I discovered that record through Meurig Jones [location manager] in Portmeirion. My copy is an original, which I got given, but I’ve also got a reissue from Hyperloop.

When I first heard it, I thought, ‘How the fuck did something so wonderful just disappear into complete obscurity?’

It has a cool organ sound on it and it reminds me of Stereolab or Broadcast…

It reminds me a little bit of Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd too – that was a fashionable thing at the time – but it’s actually a very modern-sounding record. It sounds like bands of the Britpop era or maybe even now. It’s sort of psychedelic, but the thing with a lot of psychedelia is that the best music of that era was often made by people who’d never taken drugs or never would because they imagined what it would be like to take drugs. We’ve all grown up with Alice In Wonderland and Edward Lear – once you’d read those books, you know the associations with them, like the hookah, the caterpillar and huge mushrooms, without ever taking hallucinogenic drugs. That Mountain record is 100% authentic.

I freely admit that some of the records and selections that I like, I would have either heard originally on compilation albums, or they would’ve appeared many times on compilation records.

The purpose of what I’m trying to do is to get that kind of thing across to an audience that wouldn’t necessarily be obsessive record collectors, nutters and boffins like us – who wouldn’t encounter it – but, because they like what I do, and my music goes into the fucking charts – they might dig it, and it might turn them onto other things.

I think the word is ‘non-partisan’ – I just choose what is on the jukebox or what can be played on it. I don’t choose things from CDs – the one rule is that it has to have been played on my jukebox.

‘I’m trying to get across to an audience that wouldn’t necessarily be obsessive record collectors, nutters and boffins’

I like what I would describe as quite a broad church, so there will be a hillbilly record next to something that’s psychedelic or some insane garage thing. A lot of compilers will be interested in something because it’s insanely rare, like all that freakbeat stuff… If it’s got a slightly skipped drum beat and a fuzz guitar, ‘oh, it’s freakbeat…’ A lot of it’s just shit!

You mentioned hearing songs on other compilations…. You first heard Sleepy Hollow by The Last Word, which you’ve included on your collection, on a Pebbles compilation. It’s the only record that The Last Word ever made – you paid $50 for it, but you say it’s now worth almost $1,000…

Back when I bought it, $50 was a lot of money. A lot of records I just picked up along the way and a lot of them I can’t even fucking remember where. You just buy a bunch of stuff… One of the records on the album I found in some kind of wool or knitting shop in America – it was pure chance, as I was walking down the street.

There was a bundle of records in the window, tied up with ribbon. The singles weren’t for sale – the woman behind the counter said they’d bought loads of them from a junk shop or a yard sale for a display. I said that I wasn’t remotely interested in fucking knitting, but could I have a look at the records? There was a big pile in the backroom, and she was almost throwing them at me…

I think it might’ve been in Phoenix or Tucson – somewhere like that. Tucson was somewhere I looked forward to going to because it had great second-hand clothes shops. I’ve not been to America for years, and I’m not interested in going back while Trump is in power.

There’s a great Gene Vincent song on your compilation – The Day The World Turned Blue, from 1971. It has a child-like sound – a lullaby feel, like Sunday Morning by The Velvet Underground…

Yeah, but there’s obviously a darkness to it. It’s where I got the idea of using a celeste or a glockenspiel on my music. Funnily enough, darkness is brought out a lot more by using an instrument that you would’ve played in a school orchestra, rather than something heavy and adult. Gene used to do that a lot – he did it on Over The Rainbow… a lot of his ballads.

You found one of the tracks on the compilation, Fuzzy and Wild by The Ventures, in a market in Chesterfield…

Yeah – I’ve only been there once, and it was one of the many records I bought. Call me a sad fucker, but some of the happiest moments in my life have been when you find that record you’ve been wanting to find for so long. Sadly, I’m not sure those occasions will happen much anymore, because I don’t find myself in a position where I’m on a tour bus in the middle of America, and, also, America has got wise to it. You don’t tend to find those obscure records.

The irony of it is that I’ve got no qualms about buying stuff on eBay because I’m not going to be able to find the kind of music that I want to find, like Scramble by The Royal Rockers, which I told you about earlier, in a local record shop. It’s going to be from somebody on eBay who found it in a yard sale in Seattle.

So, you found a lot of records while you were touring America with Longpigs?

A lot of them were with Pulp and Longpigs – the last tour that we did with Longpigs. I kept it quiet from them [Longpigs]. I never really talked about it much because they weren’t remotely interested in my interest in rock ‘n’ roll history.

‘Call me a sad fucker, but some of the happiest moments in my life have been when you find that record you’ve been wanting to find for so long’

I’d go wandering… When you’re out on the road for that length of time… I tried really hard to avoid being off my fucking head a lot, although, like a moth to a flame, I seemed to find enough time to discover recreational pursuits for getting into altered states. But that’s so far behind me now – 25 years in fact. I loved the idea of finding random piles of records in gas stations, or in a window display, in a ladies’ outfitters – that was where the fun was.

You said earlier that you’ve run out of space in your seven-inch singles cabinet, and you’ve got overspill. Is your wife very understanding when it comes to your records?

She’s very understanding, but it’s getting to the point where stuff’s on the floor and I don’t have shelving. I’m 58, so maybe it might be time to offload some stuff… I don’t know… When I’m gone all that stuff is probably going to end up in landfill or a junk shop anyway.

I look at a lot of the indie stuff I collected when I was a teenager… and I’ve got daft stuff like Hot Chocolate and the Bee Gees… I’ll play those records when I DJ, but, actually, I can live without them, and they get in the way of what I really want to listen to.

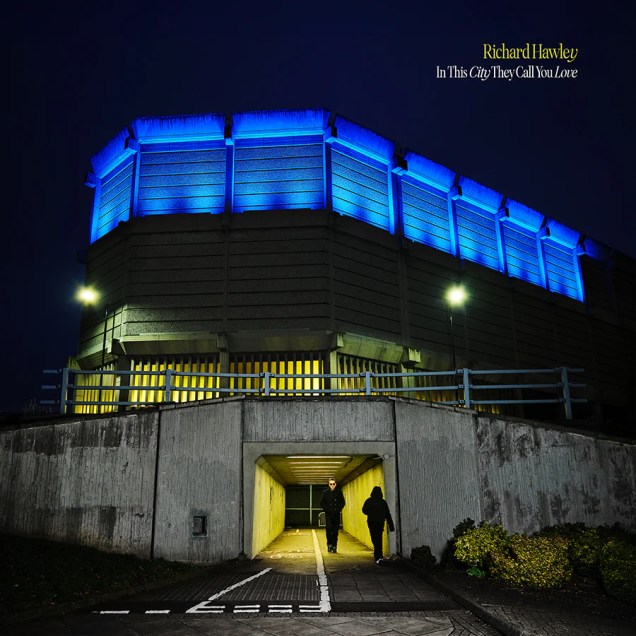

So, finally, what are your plans for 2026? You’ve had a busy few years, what with the Standing at the Sky’s Edge musical, the release of your last album, In This City They Call You Love, and the Coles Corner 20th anniversary reissue and gigs. Will you take a year off, or will you make another album?

So, finally, what are your plans for 2026? You’ve had a busy few years, what with the Standing at the Sky’s Edge musical, the release of your last album, In This City They Call You Love, and the Coles Corner 20th anniversary reissue and gigs. Will you take a year off, or will you make another album?

I don’t really know. You hit a point – and I’ve hit them in the past – which is a sort of crossroads moment. It’s the first time since I was 15 that I don’t technically have a record deal, and it’s quite a happy place. I’ve not been unsigned since I was 15! I’m 58 now, so that’s a hell of a lot of my life – 40-plus years.

I’m quite enjoying it. It’s not like I’m desperate and I’m going back to busking… I’ve just played three sell-out nights at City Hall! I find myself in a curious position – I’m 58 and what I do is getting bigger… I’m in no way bragging or being unpleasant or egotistical about it, but places that would take a month to sell out now sell out in seconds. I don’t think it’s much to do with me – I guess it’s just what’s happening in the world… People want to hear something – they’re looking for something – and my music fulfils whatever that is. I don’t think it’s anything to do with me being good…

You’re very modest…

Things are so fucked up in this world right now – we could be at war, and that’s a reality. So, me worrying about what I’m going to do next… Most musicians and artists get to bite one of the cherries in the bowl – I’ve eaten every cherry and the fucking bowl as well! I’m incredibly lucky. Fortune has been very kind to me over the years, but I’ve struggled in the past – we struggled to eat properly when my daughter was young.

That’s the road you must go down if you want to pursue what you do, rather than stacking shelves, which would be the alternative for me. I’m not a guy with a lot of paperwork to tell the world I’ve got any level of intelligence that it can measure. I wouldn’t be swapping this life to become Emeritus Professor of science or physics at Cambridge University. It would be ‘Hello, Tesco…’

‘Most musicians and artists get to bite one of the cherries in the bowl – I’ve eaten every cherry and the fucking bowl as well!’

I guess I’ll stick to what I’m doing, but I’m in no rush, although I never was. I’ve always done things at my own pace. Call me old-fashioned… I probably will make another record, but there are so many songs that I haven’t recorded… It might be time for me to archive a lot of stuff. Sometimes I’ll start singing a song that I wrote 20 years ago that I didn’t really document properly. It’s a bit like having a brain that’s like some kind of primordial soup – occasionally a bone will surface…

For every record that I’ve done, there’s so much surplus stuff and it’s not low-quality – they’re good songs. You can only fit so much on a record. I keep writing new stuff all the time. It’s not particularly a talent – it’s more of a mental illness. We’ll see…

Little Bangers From Richard Hawley’s Jukebox, Volume 2 is released via Ace Records on January 30. You can preorder it here.