The recent Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, has thrust the legendary singer-songwriter’s classic ’60s period back into the spotlight. Now a new book by UK author and journalist, Sean Egan, examines how and why during that decade, Dylan made some of the greatest and most influential recordings of all time.

Drawing on exclusive interviews with people who worked with Dylan in the ’60s, including musician Al Kooper and photographer, Daniel Kramer, Decade Of Dissent: How 1960s Bob Dylan Changed The World is a fascinating, accessible, and well-written book, offering some fresh insights into arguably the most important and revolutionary period in pop/rock music.

Egan isn’t afraid to speak his mind, either — he can be scathing about certain Dylan songs or albums, but backs up his opinions with solid arguments. He’s got a lotta nerve…

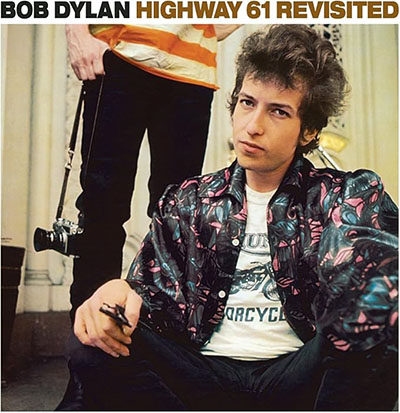

In an exclusive interview, Egan speaks to Say It With Garage Flowers about why and how he wrote the book. He also shares some of his favourite Dylan songs and explains why Highway 61 Revisited is the album that’s singularly most responsible for transforming popular music into what we know it as today.

“Highway 61 Revisited changed the rules for everything,” he tells us.

Q&A

After The Beatles, Dylan is arguably the most written about rock musician. Why did you decide to write another book on him — you’ve already done The Mammoth Book of Bob Dylan —and what did you set out to achieve with Decade of Dissent? What did you feel you could say that was new?

Sean Egan: I’m not sure there’s ever anything completely new to say about such a well-trodden subject — it’s the way that you say it.

What is new, though, is plenty of never previously published quotes and anecdotes from musicians who worked with Dylan in the ’60s, who I interviewed a few years back for a magazine article on Highway 61 Revisited. I was left, as per usual, with a lot of material that didn’t make it into the feature because of lack of space.

Why did you decide to concentrate on Dylan’s ’60s period? Did you ever consider a book on just his ’70s or ’80s work, or the religious years, or his latter records? Why not write about a period that hasn’t been so well documented?

Sean Egan: I decided to focus on the ’60s because although Dylan has made great albums since then, that was the calendar decade in which he was most influential and in which he was at the peak of his artistic powers.

In the ‘60s, he never stopped moving forward, going from protest with his second and third albums to more generalised beatnik poetry on his fourth album, and going electric in 1965 with all the magnificent results we hear on Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde.

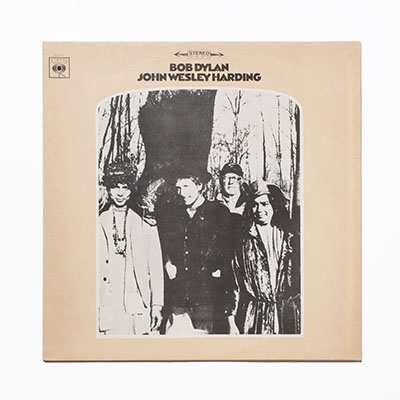

Then we have those weird albums, The Basement Tapes (if we can call that an album – I deal with the demo tapes in circulation at the time in the book) and John Wesley Harding. In those songs he seemed to totally disavow his hipster aura for something that was penitent and quasi-religious and did so to the accompaniment of very rootsy, bare music. Even Nashville Skyline is interesting in a sense because it sees him embracing corny country clichés, which nobody saw coming.

The reason his ’60s material has been so well documented is simply because that is the best and the most influential material. There’s also the prosaic fact that I didn’t actually have much already existing interview material on the latter years.

How long did it take to research and write the book and how much of it relied on first-hand interviews undertaken by you?

Sean Egan: You could say that it took me 15 years altogether because that was how long ago the interviews were conducted for the Highway 61 Revisited feature.

‘The reason Dylan’s ’60s material has been so well documented is simply because that is the best and the most influential’

In terms of physical writing, it didn’t take me that long, perhaps six months, and then the process of reading and rereading — even after it being submitted to the publisher — because endless honing is the way that I work.

Did you learn anything new or surprising?

Sean Egan: What is always surprising is the way that people’s memories differ. So, for example, Al Kooper swears that he gatecrashed the Like a Rolling Stone session — it’s quite a famous anecdote — whereas Al Gorgoni says that he invited him to the session after meeting him by chance on the street outside the studio.

Also, Daniel Kramer, the photographer, remembers Dylan giving musicians a lot of advice, but the musicians were always complaining to me that Dylan gave them no guidance whatsoever and they were essentially dancing in the dark.

Who were your favourite people to interview and why?

Sean Egan: I think Kramer was probably my favourite, simply because he hadn’t been spoken to as much as the musicians and he had a lot of interesting recollections about Dylan’s attitude about being photographed and about creating a public profile of himself. Dylan has always been interested in image and has never been the purist totally into the music that his songs might suggest.

‘The musicians were always complaining to me that Dylan gave them no guidance whatsoever and they were essentially dancing in the dark’

What’s your favourite Dylan song and album?

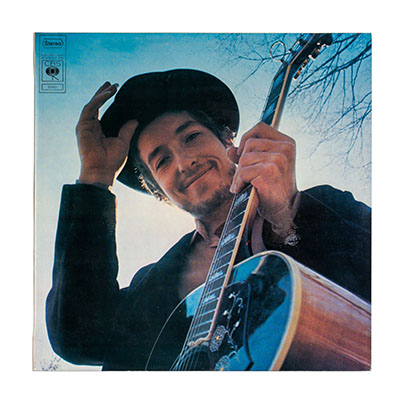

Sean Egan: My favourite Dylan album will always be Highway 61 Revisited. It’s got everything. It starts with Like a Rolling Stone and ends with Desolation Row, and those two songs alone are enough to make anybody’s reputation, but there’s lots of fantastic stuff sandwiched in between. Including surprisingly, It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry, which is not only a beautiful ballad, but it’s also an impressionistic song and we don’t really expect impressionistic songs — by which I mean sound paintings — in Dylan’s canon because we associate him with sparkling words, with music as a secondary factor.

In terms of songs, It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry is up there, as is Like a Rolling Stone, as are so many other things, but I have to nominate a bit of an obscurity: Up to Me. It was an outtake from Blood on the Tracks first released many years later on Biograph.

I enjoy your writing style and some of your observations, but I don’t always agree with your views. For example, in the book, you are quite dismissive of Positively 4th Street, which is one of my favourite Dylan songs… You think it’s too reminiscent of Like a Rolling Stone… Can we at least agree that ‘You got a lot of nerve to say you are my friend… ‘ is one of the greatest opening lines in a song ever?

Sean Egan: It definitely is one of the greatest opening lines, but it takes more than that to make a great song or a great recording. Al Kooper played on both of those songs and he himself said to me that Positively 4th Street just seemed like part two of Like a Rolling Stone. It’s people’s different opinions that makes life interesting.

Nashville Skyline is my favourite ‘Sunday morning album,’ but you’re not a big fan, are you? In the book, you call it: ‘half engaged and lazy…’

What’s your main beef with it? Admittedly, it’s not up there with his mid-’60s run of great albums, but it’s a nice album with some good moments, like, I Threw It All Away, which I think is one of Dylan’s best songs… Do you really think it’s such a bad album?

Sean Egan: It’s very slick and professional and it’s got a couple of classic songs in the shape of Lay Lady Lay and Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You, and if anybody else had made it, it would probably seem a much better album.

The trouble is that we associate Dylan with something more elevated. In fact, he is the very person who made songs and albums like that seem inadequate because he was the first person to prove that you could do so much more with popular music than just load it with clichés and romantic convention.

In the book, you say that Highway 61 Revisited is the album that is singularly most responsible for transforming popular music into what we know it as today. Can you elaborate on that?

‘Highway 61 Revisited changed the rules for everything. It proved that you could have a hit single with a six-minute scathing put down like Like a Rolling Stone, and that you could come up with a magnificent, poetic opus like Desolation Row, which spans 12 minutes’

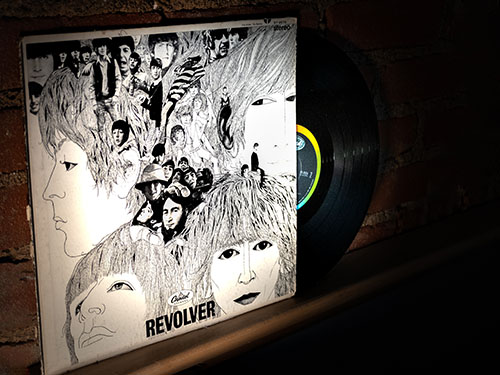

Why do you think it’s that important? Some people might make the case for The Beatles’ Rubber Soul or Revolver being more influential — I think the latter is the greatest album of all time — but I guess as Dylan influenced the mid-’60s Beatles so much, as you explore in the book, you would argue that Highway 61 Revisited is a more important record?

Sean Egan: Both of the two albums you mentioned came after Highway 61 Revisited and were influenced by them, so while it’s up for debate which of the three albums is the better one, it’s not up for debate as to which one is the more influential.

Highway 61 Revisited changed the rules for everything. It proved that you could have a hit single with a six-minute scathing put down like Like a Rolling Stone, and that you could come up with a magnificent, poetic opus like Desolation Row, which spans 12 minutes and which seems to take in just about every injustice and iniquity and hypocrisy on the face of the planet.

Just imagine being a Beatles or Stones or Dave Clark Five fan being exposed to material like that and the kind of effect it has on your mind. Then imagine that multiplied millions of times over and you can begin to get a grasp of just how revolutionary Dylan and his art were. Teenyboppers were being exposed to ideas that had never crossed their minds before.

I would argue that ’66, with Pet Sounds, Revolver and Blonde On Blonde, is a better and more groundbreaking year for rock / pop music than ’65, but would you make a case for ’65 being more important?

Sean Egan: Sixty five and ’66 are probably equally important but I think it’s an illusion that ’66 was aesthetically an improvement. I like Rubber Soul better as an album than Revolver, and Highway 61 Revisited better than Blonde On Blonde, and the two Beach Boys albums from ‘65 more than Pet Sounds. All of those ‘66 albums were very, very slick and sophisticated-sounding but they to me don’t quite have the soul or the range of the ‘65 records. For me, the two greatest years for popular music are 1965 and 1979.

Have you seen A Complete Unknown and, if so, what did you think of it?

Sean Egan: Everybody’s asking me that at the moment, for obvious reasons, and the answer to the question is ‘no I haven’t.’ This is a deliberate thing, as it irritates me the kind of liberties with the facts projects like that take, by necessity, admittedly. Life doesn’t lend itself to the kind of tidy narrative and poetic juxtapositions that filmmaking demands.

I will watch it out of curiosity when it ends up on television and I’m pleased that it’s out there because it keeps Dylan’s name alive to new generations of people, but nobody should go to a film like that expecting it to be the exact truth.

‘I don’t know whether a new album’s coming soon and maybe Dylan doesn’t even know, but he might get up one morning and decide he’s got the itch to record or write again’

Have you met Dylan? If so, what was he like? And, if you haven’t, would you like to meet him, and what would you say to him / ask him?

Sean Egan: I’ve never met him. He’s one of the few heroes on my wish list I haven’t interviewed. Naturally, I’ve got some questions in the back of my mind that I’d ask him were I ever lucky enough to encounter him, but I’ll keep those to myself just in case that lucky day comes.

Do you think we’ll get a new Dylan studio album anytime soon?

Sean Egan: He’s at that stage of his life where he can record when he wants to and where his whims are the whims of a man who doesn’t have anything to prove anymore. I don’t know whether a new album’s coming soon and maybe Dylan doesn’t even know, but he might get up one morning and decide he’s got the itch to record or write again. He’s given us enough in his life in any case that we can all be satisfied and grateful for the pleasure he’s already given us.

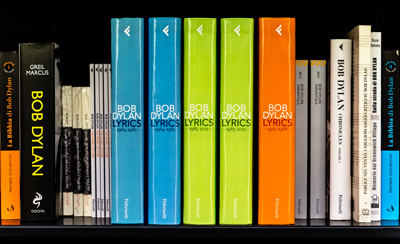

Can you recommend any good Dylan books to read other than your own?

Sean Egan: Elijah Wald’s Dylan Goes Electric, which A Complete Unknown is partly based on, is a good summary of why Dylan going electric was so seismic in both music and culture, and he knows a lot more about folk history than I ever will.

Clinton Heylin is the man when it comes to covering the entirety of Dylan’s career, even if he does tend to be a bit snippy about other writers. I’ve lost count of how many books he’s done. His depth of knowledge is incredible.

Decade Of Dissent: How 1960s Bob Dylan Changed The World by Sean Egan is published on May 20 (Jawbone Press).