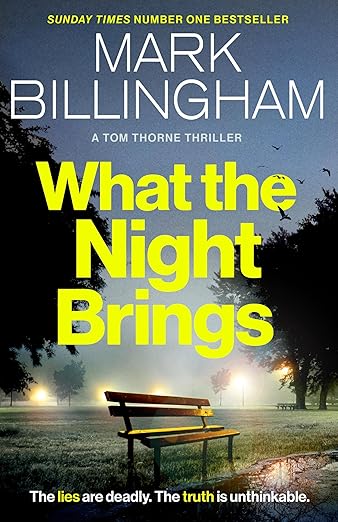

It’s been 25 years since former comedian and actor, Mark Billingham, became a crime writer, and this month sees the publication of his twenty fifth novel, What The Night Brings.

Since his first book, Sleepy Head, which came out in 2001 and introduced us to country music-loving detective, Tom Thorne, Billingham has sold over 6.5 million novels, had 24 Sunday Times bestsellers and spent more than 150 weeks in the top ten.

His latest novel – the nineteenth entry in the Thorne series – sees the lead character trying to crack what could be his most shocking case yet.

The book starts with the cold-blooded murder of four police officers – the first in a series of attacks that leaves police scared, angry and, most disturbingly of all, vengeful.

The book starts with the cold-blooded murder of four police officers – the first in a series of attacks that leaves police scared, angry and, most disturbingly of all, vengeful.

Influenced by recent real-life criminal cases, including the 2021 murder of Sarah Everard by off-duty Metropolitan Police constable, Wayne Couzens, What The Night Brings is also the first of Billingham’s books where he’s had to include an author’s note pleading for readers not to reveal any spoilers, as there’s a double whammy of shocks and reveals at the end of the novel.

What The Night Brings is the first Thorne novel since 2022’s The Murder Book – since then Billingham has been concentrating on his other crime series, which features comedic copper, Declan Miller, and is much lighter in tone than the Thorne books.

Say It With Garage Flowers invited Billingham for a pint in North London pub, The Spread Eagle, in Camden, which, funnily enough, is mentioned in two of the Thorne books, including the latest one, to reflect on his 25 years of writing crime fiction, talk about the inspiration for What The Night Brings and get his views on the current trend for celebrities writing crime novels.

“Sarah Everard was the starting point for the new book – I knew that was what I wanted to write about. Not that case specifically, but about the changing attitudes towards policing,” he tells us. “You can’t just write about jolly coppers solving murders anymore.”

Q&A

It’s 25 years since you started your career as a crime writer and you’re just about to publish your twenty fifth book. How does that feel?

Mark Billingham: It feels like five minutes… It’s crazy – when I’m working and I turn round and see all the hardbacks lined up on the shelf behind me, I think, ‘where did they come from?’ It’s bizarre – every time I think, ‘Oh my God – this is ridiculous, and I’ve been doing this far too long…’

I’ve just read Michael Connelly’s fortieth crime novel, and Val McDermid has written 35, so I’m not too much of an old dog yet… But, yeah, 25 years… When you start, you can’t possibly think that you’ll be around that long – you don’t even know if you’ll do any more than two books…

I do a book a year – people think that must be hard, but if you write full-time it’s not. What else am I going to do? I don’t think you’ve got any excuse not to write a book a year when you don’t do anything else… I do do other stuff…

But that mostly involves promoting your books…

Mark Billingham: Yes – that’s just having fun…

Your debut novel, Sleepyhead, was published in 2001, and made it onto the Sunday Times Top Ten Bestseller list. Why did you become a crime writer after being a comedian and an actor?

Mark Billingham: I’d always written – stories at school, and plays and poems, I used to sit in my room, listening to The Smiths, thinking Morrissey understands me, while writing poems, looking out at the rain.

Did you plan on writing a series of books?

Mark Billingham: When I wrote Sleepyhead, I went into meetings with a bunch of publishers and they asked me if it was the start of a series – I just said, ‘Yes,’ without even thinking about it. I was a big fan of series fiction, and I’d read Michael Connelly, Ian Rankin, and John Harvey, but I didn’t quite have the confidence to think it could be a long-running series.

‘I used to sit in my room, listening to The Smiths, thinking Morrissey understands me, while writing poems, looking out at the rain’

I knew that once I’d done the deal and signed with a publisher, I was going to write two books, but I didn’t really think beyond that. You’d be quite egotistical if you were thinking you could write a dozen of them, because nobody would pay you to write them if they weren’t selling… I got very lucky – the first two books did very well, and I was away.

Thorne has been such a successful character. What’s his appeal and what’s kept you interested in writing about him for so long?

Mark Billingham: What’s kept me interested is that I don’t know anything about him – I know as much as there is in the books… That’s all there is – there’s nothing else, no bible or dossier of facts. I’m just writing him book by book and seeing how he changes.

You’ve never really described what he looks like, have you?

Mark Billingham: Not really. I briefly described him in the first book, but when it was the twentieth anniversary of Sleepyhead and there was a new edition, I took it out. There’s no big description of him because that’s the readers’ job – to put the flesh on the bones. I don’t really describe any of the major characters – I don’t need to because I know what they think and I’m looking at the world through their eyes.

Over the 19 Thorne books, how have you noticed yourself change with him?

Mark Billingham: Well, obviously there’s the age thing… I started ageing him in real time and then stopped because I was running out of road very quickly… When I started writing about him, I stupidly made him the same age as me. So, I made the decision that even if it’s a year between books, it doesn’t necessarily mean he’s a year older – there’s not a year between cases… The next book might start two months after the last one finished. He’s not ageing as fast as I am, but we’re broadly in the same area.

How much of you is there in Thorne?

Mark Billingham: Not that much – not as much as there is in Declan Miller, who is much more like me, because of his comedic instinct. Thorne doesn’t have that, and I wouldn’t want to do what he does, but I’d quite like to have a pint with him and talk about Hank Williams all night. So, apart from our taste in music and our support for an ailing football team…

Although you support different teams…

Mark Billingham: Yeah – I’m Wolves and he’s Spurs.

How easy do you find it to come up with new plots, twists and scenarios for your books?

Mark Billingham: It’s not easy, but something always turns up. I think writers that have been doing it a long time – especially a series – live in fear that we’ve already spunked away our best ideas. Maybe we peaked at book ten… Touch wood, I don’t think that’s the case – I think the new book is as good as anything I’ve ever written, and long may that continue. But in terms of the big ideas and the big hooks… you can’t just pull them out of a hat, like a rabbit. It’s not really about that for me anymore – there’s no great hook in the new book, like there was with Sleepyhead or Scaredy Cat, but there are shocks and surprises. There’s not an elevator pitch that will make people go ‘ooh’ – it’s much more about character.

‘I think the new book is as good as anything I’ve ever written, and long may that continue’

It’s such a cliché to say, ‘character comes from plot, and plot comes from character,’ but it absolutely does. Thorne changes book on book, but in the course of this book he changes a lot. By the end of it, he’s very different than he was at the beginning because he’s seen and become aware of some very disturbing stuff.

Do you still enjoy writing new books, or do you get apprehensive?

Mark Billingham: I enjoyed this one a lot because I’d had two years off, writing the Declan Miller books, so I couldn’t wait to get back to Thorne. In the past, I might’ve had a year off to write a standalone and come back fired-up, but, after two years, I was fired-up and a bit apprehensive… It took a few weeks until I went, ‘There he is…’

I was writing chapters and thinking, ‘That’s Miller’s voice… what I am doing?’ It took a couple of weeks to get back inside Thorne’s head.

Miller is much lighter – don’t get me wrong, I love writing him, and I’m currently writing book number three – but it’s nice to be able to have a change of pace, take a breath and not worry if I’m thinking of a stupid joke because it just goes in… I think of a stupid joke for Thorne sometimes, but I can’t put it in because he wouldn’t say it…

My first instinct is always comedic – if someone tells me something, I’m looking for a joke, even when something tragic happens. I’ve become obsessed with jokes as a coping mechanism in the face of really dark stuff.

We’re not giving away any spoilers for What The Night Brings, but we can say it’s got some shocks in it…

Mark Billingham: It’s the first time in 25 years that I’ve had to write a note at the back of the book saying, ‘Dear reader, I beg you, please don’t let on what happens at the end…’

We all hate spoilers, and we all live in fear of a review giving something away, but there are some big reveals in this book, and I want them to stay hidden until the end. I want it to be like a kick in the teeth… It’s a different book for me, because, if you’re writing police procedurals, which I am, broadly speaking, you can’t do it anymore without tackling certain issues – it’s become a different ball game.

‘We all hate spoilers, and we all live in fear of a review giving something away, but there are some big reveals in this book, and I want them to stay hidden until the end’

I saw how some American crime writers changed after George Floyd – the police were no longer the good guys, and when they arrived on the scene, people didn’t want to see them. The new book is my reaction to Sarah Everard and that kind of stuff…

We can say that the book starts with the murder of four police officers, and it deals with some of the issues that have led to the police being under intense scrutiny, like the murder of Sarah Everard…

Mark Billingham: That was so shocking – not just the case but the general figures. There are enough coppers on suspension at the moment to police a small town. I was getting quite worked up writing the book, as I was looking at some of the facts and figures and going, ‘Jesus – this is absolutely horrendous.’

Sarah Everard was the starting point for the new book – I knew that was what I wanted to write about. Not that case specifically, but about the changing attitudes towards policing. It’s no longer about the one bad apple… it’s about an awful lot of bad apples. Once an official report says the Metropolitan Police are racist and misogynistic, you say: ‘What the hell?’, and you’ve got to write about it. You can’t just write about jolly coppers solving murders anymore.

That said, it’s important to point out that I’m not writing polemics – I’m not interested in tub-thumping, and I haven’t got an agenda. I’m still trying to write an entertaining and commercial crime novel, but that issue was bubbling away in the background.

Thorne is a detective, but I also wanted to write about the mood on the street amongst uniform coppers.

It’s not the first time you’ve written about contemporary issues – Love Like Blood tackled honour killings…

Mark Billingham: To avoid an issue would mean that you end up writing a cartoon – it would be so egregious to not write about it. I’m not lifting things directly from the news, but you’ve got to reflect attitudes and what’s happening in the world.

I still have nothing but admiration for the good coppers, who do an incredibly difficult job – it’s certainly a job that I could never do – but I’ve got nothing but disdain and hatred for the bad ones.

Writing crime novels seems like it’s become the fashionable thing to do. We’ve seen Richard Osman, Richard Coles and Richard Madeley – all the Richards – among others – try their hand at crime fiction. Why is there a trend for it?

Mark Billingham: I think in a number of cases they’re approached by publishers who go, ‘How do you fancy writing a crime novel?’ Or, without mentioning any names, ‘How do you fancy putting your name on the front of a crime novel that somebody will write for you?’

As a long-established crime writer, how does that make you feel?

Mark Billingham: I’ve got no issue with celebrities writing crime novels – Richard Osman’s books are great – and there are plenty of people who are famous for other things writing good crime novels, but there are celebrities who aren’t writing them, but, quite disgustingly, have their names on the front of them. That really pisses me – and every writer I know – off.

I don’t mind books being ghost written if the celebrity in question fesses up to it and is honest about it, but the vast majority of them aren’t. They’ll go on TV and talk about how much they enjoyed writing the book.

‘I’ve got no issue with celebrities writing crime novels, but there are celebrities who aren’t writing them, but, quite disgustingly, have their names on the front of them. That really pisses me off’

It’s a terrible trend and it’s not just the places in the bestseller lists they’re taking up – it’s places at festivals that other writers could be doing.

Have you read anything good recently?

Mark Billingham: Yes. My new crime writing crush is a writer called Dominic Nolan – he is absolutely fucking brilliant. He makes you want to give up. His last two novels, Vine Street and White City, are unbelievably good. He doesn’t write a book a year, like the rest of us hacks, but he’s phenomenally good. I’ve just read the new Ian Rankin book [Midnight and Blue], which is great. He’s still knocking it out of the park after however many books.

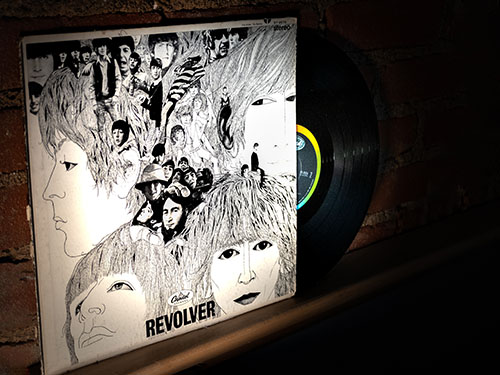

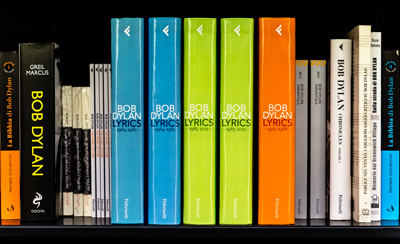

But I put everything to one side if there’s a new Beatles book to read. There are so many books I should be reading, but if there’s a book about The Beatles…

What The Night Brings is published on June 19 (Sphere).